By Margaret Morales

The 2001 Stockholm Convention was convened to draft a global treaty for the regulation of persistent organic pollutants (POPs). POPs are a class of highly toxic chemicals which do not degrade in the environment, but can accumulate in animal body fat and, as a result, bioaccumulate up the food chain. They also can easily travel across various media, including air, water, and soil, making them extremely mobile and rendering country borders a useless defense.

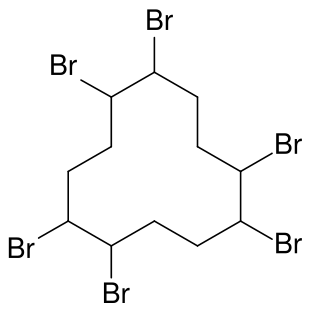

The original Treaty focused on eliminating or reducing the production of 12 key POPs, dubbed the ‘Dirty Dozen.’ Since then, 10 additional chemicals have been added to the list of POPs regulated by the Treaty. Among the substances regulated are a number of toxins studied here at Duke’s Superfund Research Center, including PCBs, and three common flame retardants.

Since 2001 179 countries have ratified the Treaty, yet the United States remains one of a handful of countries that has yet to do so. Though George W. Bush signed the Treaty in 2001, ratification to put it fully into effect in the US requires both a 2/3rds support vote from the Senate, and a legal framework to support the Treaty’s stipulations. Currently two key US laws differ significantly from the Treaty and would need to be changed in order to proceed with ratification. These are the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), which has never been amended since its inception in 1976, and the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA).

Although the US hasn’t ratified the Stockholm Convention Treaty, it has implemented several measures that parallel the Treaty’s regulations; for example, use of all of the original Dirty Dozen substances is already banned within the United States. Nevertheless, the US continues to manufacture for export some of these chemicals, such as chlordane, an agricultural pesticide. In addition, the US continues to manufacture and use several of the more recently added POPs to Stockholm Convention, including three common flame retardants.

Besides our continued use and production of some of the chemicals regulated under the Stockholm Convention, there are a number of other obstacles to ratifying the Stockholm Convention Treaty here in the US. One that is particularly interesting is the difference between how the TSCA and FIFRA determine the potential risks of a given chemical compared with how risk is determined under the Stockholm Convention; this means of determining risk in environmental regulation is often called the ‘standard of safety.’ While FIFRA and the TSCA both employ a cost-benefit analysis to weigh the adverse effects of chemicals, thus taking into account the financial costs of any potential regulation,the Stockholm Convention uses a ‘health-based’ standard to determine risks from POPs. In my next post I’ll write about the differences between these approaches to risk analysis and some of the ethical considerations that arise from each.