By Eileen Thorsos

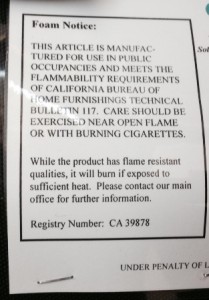

In my hotel room in Atlanta, the tag under the desk chair told me that my chair met California’s old TB 117. In order to meet that flammability standard, the foam inside the chair I sat on as I drafted this blog post must have had flame retardant chemicals in it. I don’t know which specific chemicals this particular chair has, although they likely made up at least 4% of the foam by weight. These flame retardants are intended to protect us from fires. Unfortunately, many flame retardants are also likely toxic, especially to developing children. And, as furniture ages, the chemicals in a chair or couch may escape and expose people in the room: We all have flame retardants in our bodies. That’s why I was at the hotel.

Dr. Heather Stapleton and I went to Atlanta last week, May 20-22, for the 2014 Furniture Flammability & Human Health Summit, the second such conference about flame retardants, furniture, and human safety: safety from fires and safety from potentially toxic chemicals. The conference brought together key stakeholders from many perspectives, including environmental chemists and toxicologists, flame retardant manufacturers, fire safety researchers, environmental health advocates, firefighters, flammability standards developers, and leaders from along the furniture manufacturing supply chain.

Although I’ve learned a lot about this topic (please check out the information sheet we recently developed about possible health risks from exposure to different flame retardant chemicals!), but I’d never seen these conversations happen in person before. In fact, last year’s summit seems to have been the first to bring so many of these stakeholders together. So, I was eager to see the action and learn more about the participants.

Several questions threaded through the conference. Has using flame retardants in household furniture helped reduce fire deaths? How might we make furniture less flammable without using chemicals that, among other health risks, may decrease children’s IQs, increase our body weight, or cause cancer in consumers or firefighters?

Participants interpreted differently the role of flame retardants, as used commercially in furniture, in promoting fire safety. The data I’ve seen suggest that flame retardants at concentrations and with furniture designs used in residential furniture likely have done little to reduce fire deaths – but the data are patchy, and we’re still debating what has happened in the past. I’m surprised at how little systematic data these different agencies, organizations, and companies have published about how different concentrations of common flame retardants affect the way furniture burns.

When it comes to making furniture that is unlikely to either ignite or be toxic, many of these stakeholders have become intrigued with using fire barriers between the outer fabric and the inner foam, which may also do much more to promote fire safety than flame retardants mixed into the foam. During the conference, I spoke at lunch with a manufacturer of such barriers, Kyle Bullock from Preferred Finishing, Inc., who explained how he uses phosphorus and nitrogen-based chemicals that, when heated, swell to separate the foam inside from fire. He believes his system is not toxic, but the exact chemicals he uses are a trade secret.

I heard elsewhere at the conference that such barriers are labor-intensive to sew, so furniture makers think it’s currently unrealistic to use barriers in cheaper furniture. Also, padded couches and chairs in public buildings like schools or hotels, it turns out, typically have fire barrier layers that leave them extra firm. Do you want furniture that feels institutional in your home? The furniture makers don’t think so.

Some companies and researchers promoted a newer type of flame retardant that involves large polymers – molecules with long chains chemically bound into the foam, molecules so large that they degrade to molecules that are also large. Our bodies should be less likely to interact with such large molecules, so this design might reduce their riskiness. (I don’t know much of anything about potential health risks from this type of flame retardant.) Furniture makers, however, are concerned that so far these compounds stiffen foam, which makes them less comfortable in a couch cushion.

I hear that last year’s discussions were a little tense. This year, with one exception, the participants at the summit spoke respectfully even when they interpreted fire death statistics, furniture burn data, or toxicity results differently. Multiple people who I spoke with, from many perspectives, brought up how important it is for us to listen to each other and to think outside of our own boxes in order to figure out the best path to protect safety on all sides.

So, I sense that these conversations are helping… slowly: I see the stakeholders providing feedback to each other, including about how to make their work more relevant to each other. Animal experiments in the lab showing that exposure to even low levels of flame retardants used today cause developmental problems in fish and rats and studies in people that reveal relationships between concentrations of flame retardants in their bodies and certain health problems have changed the conversation. Last year, California revised its flammability standards for residential furniture, and now Technical Bulletin 117-2013 can be met without adding flame retardant chemicals to foam.

Our furniture and many other consumer products still have concerning levels of flame retardant chemicals that likely cause health problems. (If you’d like to know what is in your furniture, send us a sample to test.) Seeing major furniture manufacturers and people who develop safety standards grapple with these questions, however, leaves me a little encouraged about a future where the furniture in our homes – and our hotels – doesn’t expose us to toxic chemicals.