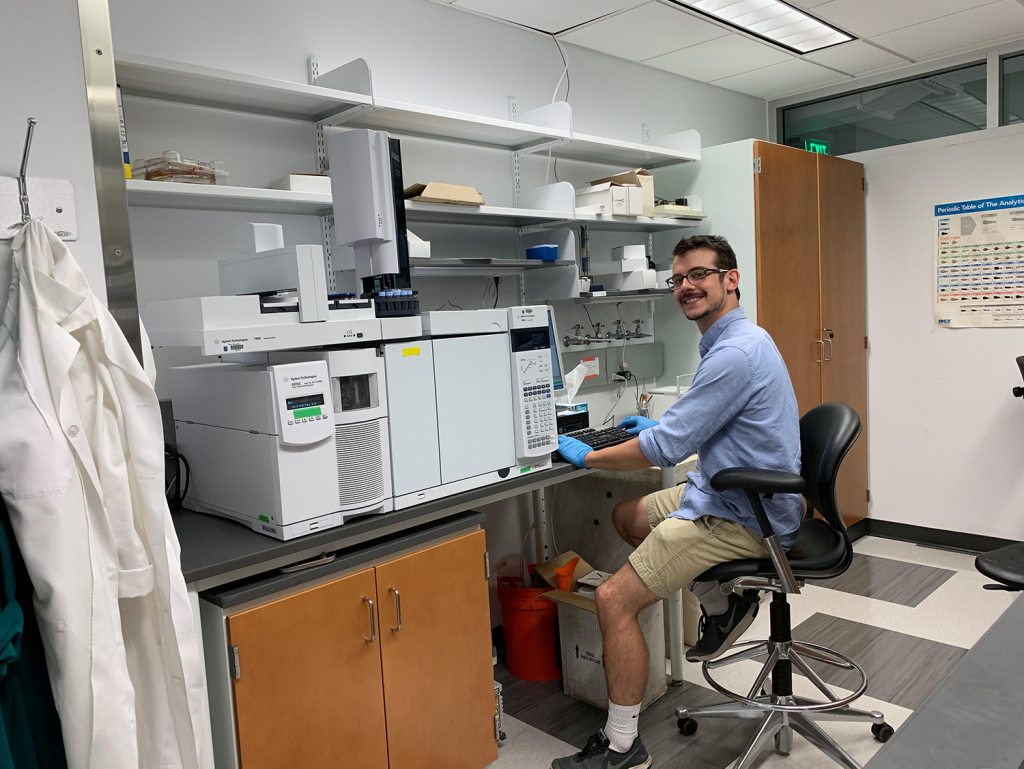

By Patrick Faught, Summer Research Intern, Ferguson Lab, Analytical Chemistry Core

This summer I am working in Dr. Lee Ferguson’s lab to quantify the extent of poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in the state of North Carolina. PFASs have been extensively used in commercial products over the last 60 years, from cardboard boxes and non-stick pans to firefighting foam. PFAS are ubiquitous in the environment and stick around for a long time before they degrade. PFAS exposure has been linked to cancer, higher cholesterol, obesity, immune suppression, and endocrine disruption. While some of the longer-chained PFASs have been phased out in manufacturing, there are still an estimated 3000 PFAS compounds in use today. Over concerns about these health effects, the North Carolina General Assembly set aside funding for Duke and 6 other universities across the state to study PFAS. Dr. Ferguson is focusing on finding where and at what level PFAS exist in drinking water throughout the state.

To accomplish this, the lab is driving to every public drinking water source in North Carolina—from Raleigh to the 158-person town of Milton. Most sources have concentrations below the EPA’s health advisory limit (70 parts per trillion of combined PFOS and PFOA), but some are at risk from nearby fluorochemical manufacturers and other industries that use PFAS, army bases which use the PFAS-laden firefighting foam, or from upstream wastewater treatment plants that are not set up to treat PFAS contamination. The most notable of these sources is the Chemours plant on the outskirts of Fayetteville, N.C, where the PFAS “GenX” was discharged into the Cape Fear River and reached Wilmington’s water supply. Additionally, some states have set regulatory standards for PFAS that are more stringent than EPA’s non-binding guidance.

Paper mills have been documented as major sources of PFAS pollution. Many paper products designed to hold food repel oil and grease (e.g fast food wrappers, paper coffee cups, etc.). One of these plants lies along the Neuse River, and we plan on taking a boat through the area of discharge to assess PFAS levels and if the discharge could affect communities downstream.

On top of quantifying the distribution of PFASs in the environment, our lab is also focusing on quantifying PFASs in commercial products. PFASs are so persistent in the environment that they can even make it through the brewing process. We’re currently working to analyze the beer from multiple breweries throughout the state to assess whether beer drinkers are being exposed to concerning levels.