By Sena McCrory, Summer Research Intern, Research Translation and Community Engagement Cores

“So, what threshold should we use for safe arsenic concentrations in garden soils?”

“Well, technically, there isn’t any “safe” level of exposure. It’s a continuous scale—it’s not as if on one side of the threshold it’s safe and the other it’s not.”

“But the gardeners will want to know what concentration of arsenic is okay and what is not okay…”

“The EPA has a health-based standard of 0.68 ppm, but that is actually lower than the typical background levels of arsenic in North Carolina’s soils. But then again, that standard doesn’t actually consider exposure from gardening activities. AND it really depends on how much of the arsenic is organic and how much is inorganic.”

“Ok, but we still need to pick a number…”

In the past month working as a science communication intern with the Research Translation and Community Engagement Cores I have had countless iterations of this cyclical conversation. What do we say about this? How do we talk about that? And the answer goes something like this: Well, it’s complicated…and it depends on this, that, and that other thing, too.

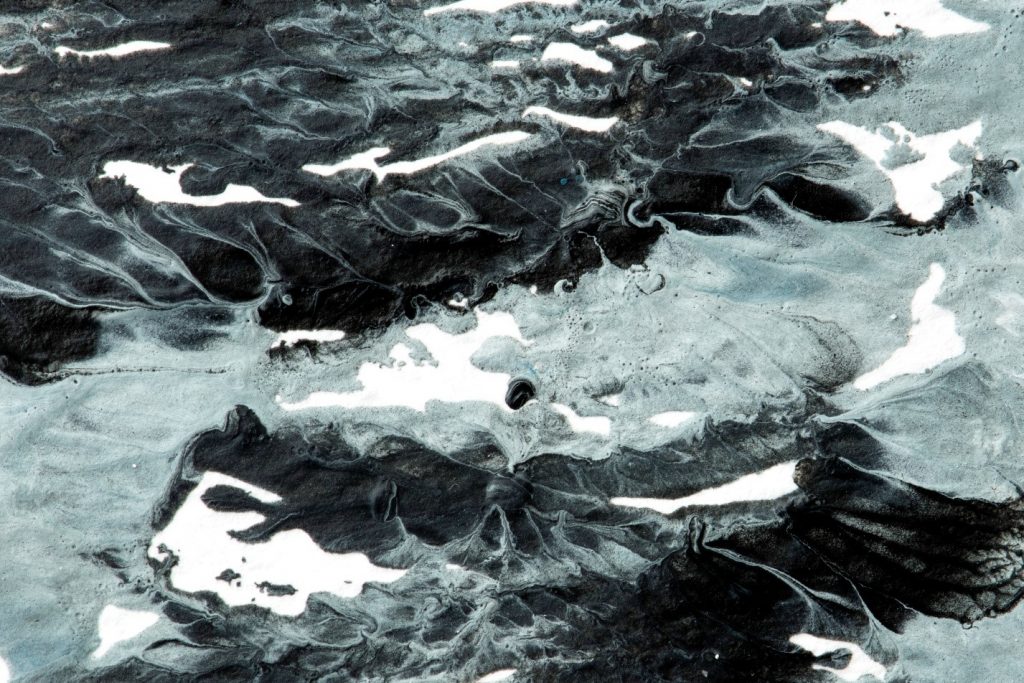

As humans we are uncomfortable with imprecision. We want answers that are black or white, but not gray. We like our coffee hot or iced, but never tepid. But science does not fit neatly into this framework. Science is chock full of unknowns, nuanced relationships, dependent variables, probabilities, and endless uncertainties. Straight answers are rare. This is the crux of why science communication is so darn difficult.

As a science translator, I am tasked with combing out the jargon and distilling what is left into easily understood, useable information. But most days it feels more like I’ve been handed a whole bucket of gray paint and told to first separate the black from the white, and then paint a picture on an index card using only those two colors.

Defaulting to my science training, my first step is to research how other people have already attempted this and learn from them. I spent my first few days reading through background information and researching existing examples on soil contamination, sources of contaminants, routes of exposure, and health impacts. Quickly I discovered that there are a lot of flawed science communication pieces out there. That one is too complicated. This one too simple. Too broad. Too specific. Too long. Too ugly. Too boring. It’s the ultimate Goldilocks dilemma—and it’s difficult to find a balance that’s just right. Unfortunately, there are no easy “science communication hacks” because, of course, it’s not that black and white.

But most days it feels more like I’ve been handed a whole bucket of gray paint and told to first separate the black from the white, and then paint a picture on an index card using only those two colors.

One of the most difficult steps in the process is deciding what information not to include. As a science-minded person I discover innumerable fascinating tidbits about my research topics as I seek to grasp the bigger picture. I battle with the urge to include all these morsels as I am forced to remove the facts that are interesting and keep the fact that are important. But what makes something important?

To answer this question, I turn to my audience. I sink myself into their shoes and take a look through their eyes. What do they want to know? What do they need to know? And what do I want them to understand or do after reading this? And the hardest question: what does my audience not need to know?

However, during this triage process I inevitably lose some of the nuance of the information. As a scientist I strive for accuracy and precision, and I wince at the thought of over- or understating the facts—or worse, omitting information. As a science communicator, however, I accept that there are limits to how much text my audience is willing read. And there are limits to how much new material can be synthesized before the main point is eclipsed by peripheral information. I remind myself that I am writing to satisfy my audience and not to satiate my own scientific urges.

After I finally fit all the relevant information onto my smaller, simpler canvas, I step back and look at what I’ve created. Does it make sense? Do I enjoy looking at it? Is it misleading in any way? Does it achieve its purpose? For the most part, yes. Inevitably, there will be parts of the piece I am still unsatisfied with—phrases that could be clearer or sections that seem incomplete—but the goal is honest and useful communication, not perfection.