Lindsay Holsen is theCEC/RTC summer intern, visiting us from Lawrence University in Appleton, WI. In addition to community engagement and research translation work, Lindsay is helping Duke doctoral student Tess Leuthner in Dr. Joel Meyer’s lab with a research project on soil nematodes and contaminated soil.

When our health is in question, scientific research immediately becomes personal.

Science is a process of constant input, review, and questioning. There is a demand for answers and a tendency to seek quick conclusions to concerning issues, especially when the answer that aligns with our pre-conceived expectations (confirmation bias) stands in contrast to the scientific process. The challenge of translating research into a journalistic story is to use caution to convey accurate information, and yet still catch the attention of readers through effective communication techniques.

In a recent case of “study” turned “story,” a preliminary cell-culture laboratory study out of Dr. Heather Stapleton’s lab gave rise to some sensational headlines. For the study, titled Characterization of Adipogenic Activity of House Dust Extracts and Semi-Volatile Indoor Contaminants in 3T3-L1 Cells (Kassotis et al. 2017), researchers incubated and exposed cultures of mouse cells to isolated house dust and a variety of other indoor contaminants. Their results suggested that the majority of the 11 house dust samples and indoor substances tested caused increased production of trigylcerides and pre-adipogenic activity in the mouse cells, which eventually creates cells similar to human “white” fat cells.

The cells were exposed at environmentally relevant exposure levels, but the authors noted that further research is needed on the bioactivity, interactions, and mechanistic activity of the chemicals on these adipogenic, or fat-creating pathways in the body. The tissue culture in vitro approach allowed valuable insight into the issue of house dust and indoor contaminants, but is a preliminary step that will require further research and exploration.

Some of the catchy news headlines didn’t always present the most accurate picture of the research findings. “Household dust makes people fat, groundbreaking research indicates” read one headline in The Telegraph. Here is what Chris Kassotis, a postdoctoral research associate in the Stapleton lab who conducted the research, said in response during an interview with Public Radio International:

“We definitely are not saying that house dust will make people fat,” says Kassotis. “This is a preliminary step on that pathway. First, we’re showing that house dust can stimulate the development of fat cells in the lab … [I]t’s a little too early to say that it would act the same way in an animal or, ultimately, in a human.”

* * *

An isolated cell in a human body, unable to communicate, cannot contribute to the incredible dynamics of the human body unless it has cytokines or chemical messengers to send out and take in information for the viability of the cell and the whole organism.

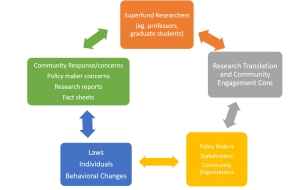

Likewise, academic research that occurs here at the Duke University Superfund Research Center requires interconnected systems to present information effectively to policy makers and communities. In turn, those impacted communities benefit when they share their questions and concerns about reducing contaminant exposures and improving environmental health with investigators. The graphic to the right demonstrates some components of the cyclical, bidirectional process of research translation and community engagement.

The aim of the Duke University Superfund Research Center’s Research Translation Core is to make our research accessible through presentations, news releases, and meetings with stakeholders and community members. Science is exciting, but it can also be concerning for the public to learn about potential health impacts of environmental exposures.

Communicating about environmental health provides an opportunity to connect with broader perspectives and influences, and yet it also runs the risk of inviting sensational coverage that can evoke emotional responses. Metaphors and visuals can make some of the complicated processes involved with pathways of exposure and contamination relatable to personal concerns without exaggerating the extent of the scientific conclusions.

To learn more about effective science communication, check out some of the following resources and organizations collected by The People’s Science: http://www.shareyourscience.org/read-me-2-1-1/.