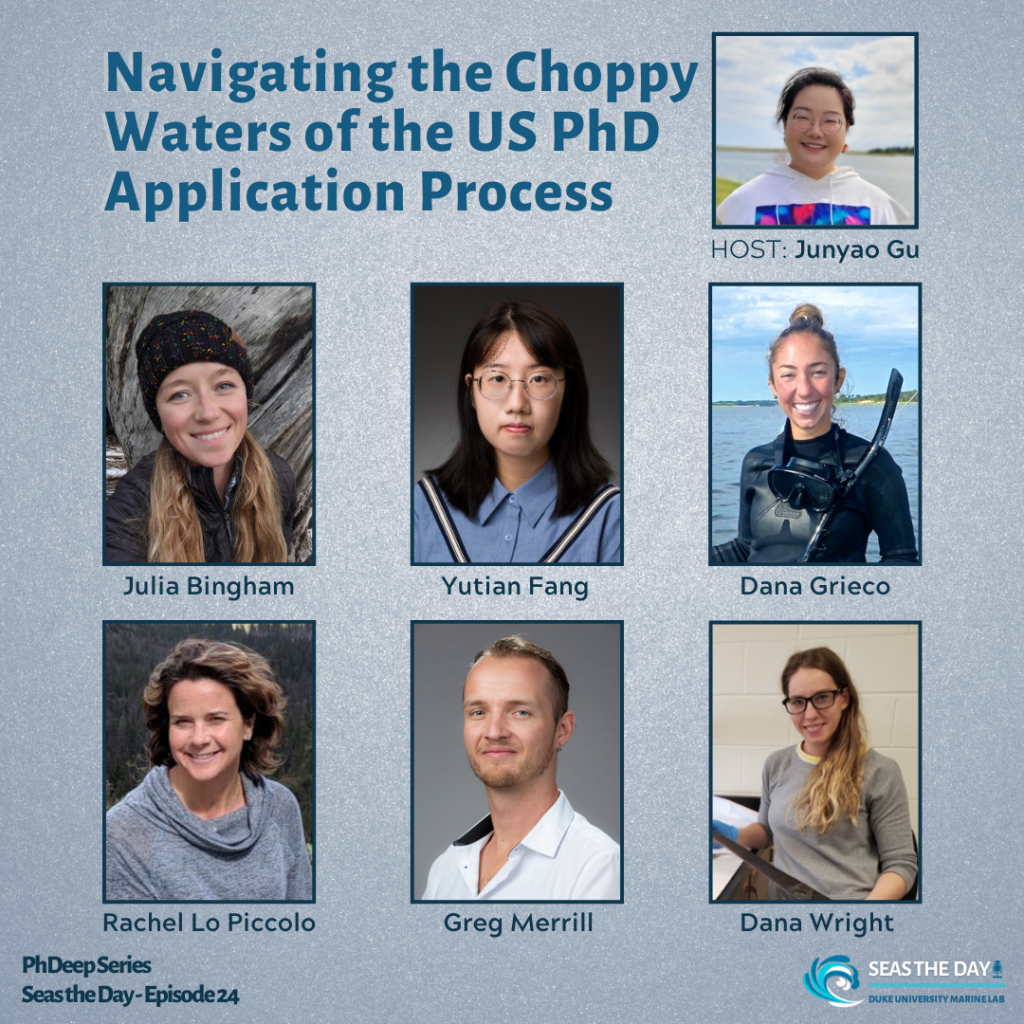

On this episode, Rafa Lobo introduces two new members of our team: Rebecca Horan and Junyao Gu. Junyao runs the show, exploring the ins and outs of a PhD program application process. She interviews five PhD students and our doctoral program coordinator, to learn about the biggest challenges, reasons to do it, tips for those wishing to apply, as well as some systemic inequalities inherent in the process – and how to potentially overcome them!

Listen Now

Host

Junyao Gu, 3rd year PhD candidate at Dr. Zachary Johnson‘s lab.

Junyao grew up in a coastal city named Lianyungang in Jiangsu Province, China. She received a Bachelor of Science degree in Environmental Science and a Bachelor of Laws degree in Law from Jilin University, China in 2017. She graduated with a Master’s degree from the Department of Environmental Health and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University in 2019, where she found her deep love for exploring the tiny mysterious microbial world and had a wonderful time doing research in Dr. Sarah Preheim’s lab. She joined Dr. Zackary Johnson’s research group as a Ph.D. student in 2019 and she currently studies the microbial ecology and metagenomics of marine phytoplankton.

Instagram: @gu_junyao

Interviewees

Rachel Lo Piccolo, Marine Science and Conservation PhD Program Coordinator

Rachel has a BS in Biology and Spanish from the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point. She graduated from the Univercity of Central Florida with a Master’s degree in Zoology with a study on human impacts on wild bottlenose dolphin behavior in the intercostal waters of Florida. While in Florida, she began working for the marine mammal stranding network and took a position with NOAA at their Beaufort, NC laboratory as the state stranding coordinator. She continued in that position as well as teaching Biology for Carteret Community College before transition the Duke Marine Lab campus as the PhD Program Coordinator in 2010. She has continued her work at Duke with PhD students in marine conservation, overseeing a summer international Global Fellowship program and most recently has trained as a Wellness and Life Coach through the Duke Integrative Medicine Program. She is passionate about marine conservation, education and inspiring students to become the best well rounded versions of themselves. In addition, she enjoys traveling to National Parks with her family and anywhere in Maine.

Julia Bingham, 5th year PhD candidate in Marine Science and Conservation at Dr. Grant Murray’s lab

Julia has a bachelor’s degree in Biology and one in International Studies from Oregon State University. She has been an intertidal ecology research assistant at Hatfield Marine Science Center and the Oregon Institute for Marine Biology, developed environmental education plans for the South Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve, helped develop social-economic indicators of coastal resilience and equity in northern Cuba and the US Gulf Coast. She is the 2021-2022 Anne Firor Scott Graduate Fellow in Public Scholarship. Her current research focuses on environmental knowledge, social values, and equity in coastal governance and management using traditions of Political Ecology and Critical Geography. Her dissertation work is conducted in the traditional territory of Tla-o-qui-aht First Nations, with the collaboration, permission, and leadership of Tla-o-qui-aht and of Ha’oom Fisheries Society.

Twitter:@juliaabingham

Website: www.juliaabingham.com

Yutian Fang, 1st PhD student at UC Santa Barbara, Duke CEM Alumna

Yutian grew up in Beijing, China. She received her Bachelor of Science degree in Marine Biology from UC San Diego in 2019, and Master of Environmental Management Degree from Duke University in 2021. During her time at Duke Marine Lab, she found her research passion in mitigating bycatch between fishing activities and marine megafauna. Based on her interest, she is currently a Ph.D. student at Bren School of Environmental Science and Management, UC Santa Barbara. During her time at Bren, she will continuously explore using spatial tools to reduce global bycatch in data-poor environments, with her ultimate goal to create benefits for both human society and the natural world.

Twitter: @Yutian1207

Dana Grieco, 3rd year PhD student in Marine Science and Conservation at Dr. David Gill’s lab.

Dana’s current research focuses on how fisheries and conservation interventions (such as climate change and conservation interventions) impact marine social and ecological systems, with a particular focus on small-scale, data-poor fisheries systems. Her methodology includes data-limited fisheries modelling, interdisciplinary systems-based approaches, and participatory research techniques that value fisheries stakeholder knowledge. Dana graduated with a B.S. in biology from Villanova University in 2016. She spent the following three years working in marine ecological research and many facets of the fishing and dive industries in Cape Cod, MA, and the Bay Islands, Honduras. She then came to Duke to work with her advisor, Dr. David Gill, in 2019.

Twitter: @dana_grieco

Instagram: @danagrieco

Greg Merrill, 3rd year PhD student in Marine Science and Conservation at Dr. Doug Nowacek’s lab

Greg is a 3rd year PhD student in the University Ecology Program whose dissertation research is broadly focused on assessing the impacts of plastic pollution on energy metabolism in the blubber in marine mammals: whales, sea lions, seals, etc. His previous work at the University of Alaska Anchorage where he earned his Masters of Science has focused on investigating maternal foraging behaviors of Alaskan northern fur seals in an effort to establish an effective and relatively inexpensive long-term monitoring index of foraging success and pup survival in the face of climate-mediated shifts in ecosystem structuring. Greg enjoys kayaking, hiking and camping.

Twitter: @GBMerrjr

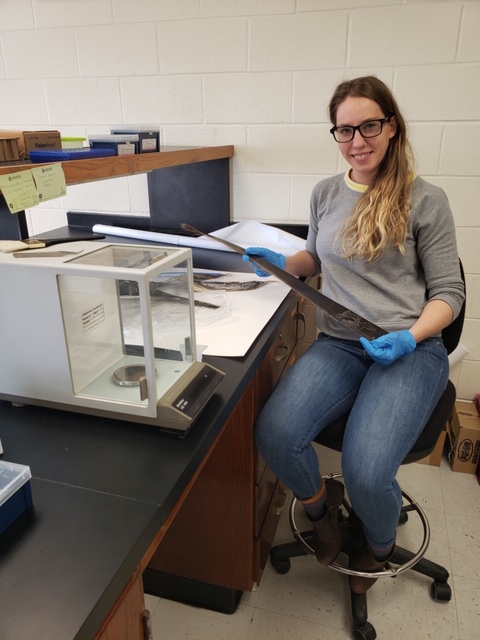

Dana Wright, 4th year PhD candidate in Marine Science and Conservation at Dr. Andy Read’s lab.

Dana is a conservation biologist and marine ecologist interested in community structure and ecological niche under changing climatic conditions. To date, her research has focused primarily on whale species in the North Pacific and subarctic. Her current research in the Read lab focuses on the conservation case study of the North Pacific right whale, a species of whale on the brink of extinction from legal and illegal commercial whaling. She graduated from the University of Alaska, Fairbanks in 2014, with a Master’s Degree in Marine Biology. After which, she started contract work for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Marine Mammal Laboratory in Seattle, WA. She started her PhD at Duke University in 2018. Dana is currently an NSF Graduate Research Fellow and has received the North Pacific Research Board Graduate Fellowship. In her free time, she enjoys swimming, hiking, and surfing.

Personal website: www.danalwright.com

Twitter: @danawr8

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/wrightdl8

Transcript & References

Navigating the Choppy Waters of the US PhD Application Process

[Oyster Waltz’ theme song begins]

Rafa: Hello listeners! It’s November. Winter is coming and so is the holiday season! But for people applying to graduate school, this also means the deadline to submit their applications is just around the corner. Although graduate school application deadlines vary from program to program, students in the US are generally encouraged to submit in November or December. I’m Rafa Lobo, your usual PhDeep host, and as you probably guessed, today we are exploring the ins and outs of applying to graduate school. But before we proceed, I want to introduce you to two new members of our team. Rebecca Horan, and Junyao Gu, both third year PhD students at the lab. Becca, do you wanna say hi?

Becca: Hello! As an avid podcast consumer and lover of storytelling, I am excited to join the team. I’m working with season on what we’re calling PhDeep Highlights. These will be quicker, more interview style episodes focused on individual students at the Marine lab highlighting what they’ve learned and achieved in their research careers and personal lives. Stay tuned!

Rafa: Great! Thanks Becca, I am looking forward to hearing them. Now, Junyao – our listeners might remember you from our international student episode. I guess you loved the experience so much you wanted to join our team?! Do you want to formally introduce yourself?

Junyao Gu: That’s right! And hi everyone, I am Junyao Gu, and I am now the third year PhD in Dr. Zackary Johnson lab working on marine cyanobacteria. It has been a fun experience producing this episode, and I hope people enjoy it!

Rafa: I’m sure they will. Welcome both, and let’s get started.

Rafa: I’ll now turn it back to Junyao, who is running the show today. Enjoy!

JG: Applying to doctoral programs is not an easy process. In 2020, Duke University Graduate School received 8968 applications to doctoral programs and 933 were admitted. The PhD acceptance rate is around 10%. Obviously, there are many challenges that arise during the application processes. How can prospective students better handle those difficulties? What wisdom can current PhD students who have successfully gone through the application process offer?

JG: In today’s episode of PhDeep, students at the Duke University Marine Lab share with us their paths to the PhD and challenges they faced during the application processes. Through our conversations, we highlight what current prospective students should be considering, but we also take the opportunity to discuss some systemic inequality issues inherent in the application process.

For this episode, I interviewed a Coastal Environmental Management alumna,

[Yutian Fang]: Hi everyone, my name is Yutian. I’m currently a Ph.D. student at Bren School of Environmental Science and Management at UC Santa Barbara.

JG: And four current PhD students.

[Dana Grieco]: My name is Dana Grieco. I am a third year PhD student at Duke. I have a Bachelor of Science in biology. After that, I kind of spent three years working in marine ecology research and environmental education.

[Greg Merrill]: My name is Greg Merrill. I’m a third-year PhD student down at the Marine Lab and I’m working with Doug Nowacek is my advisor. I grew up in California, went to college at UC Davis, and then I spent a couple of years up in Alaska getting a master’s degree working at the University of Alaska Anchorage, and now I’m here at Duke.

[Dana Wright]: My name is Dana Wright, and I was born in Twin Falls, Idaho. I did not go straight to a PhD. I went from that from graduating undergraduate directly into this master’s program in Alaska. And after I got my master’s, I had been working for five years contracting for the Federal Government.

[Julia Bingham]: My name is Julia Bingham. I’m a fifth year PhD student in marine science and conservation program in Grant Murray’s lab.

JG: I also talked to our doctoral program coordinator.

[Rachel Lo Piccolo]: Hello, my name is Rachel Lo Piccolo. And I am the program coordinator for the marine science and conservation PhD program.

JG: Welcome, to Seas the Day!

[Oyster Waltz’ theme song ends]

JG: As I mentioned, getting a PhD is never easy. According to the Survey of Earned Doctorates, earning a PhD from a graduate program in the United States typically requires six years; there are many types of programs that take even longer, such as Doctorates in the humanities and arts, where the average completion time is 7 years. Here at the Marine Lab, our degree is technically a 5-year degree, but it is not uncommon that students will need an additional year or two. Six or seven years, that’s a really long-term commitment! So, I guess the first thing people should think about when applying to a PhD program, is the reason why they want to do it. I asked my colleagues, what was their motivation to pursue a PhD.

JG: Yutian told me she was interested in a PhD because she wanted to conduct her own research.

[Yutian Fang]: I guess just I have like interests for like conducting independent research and the hope to change the world into a better place throughout my research, which sounds kind of crazy. But I mean like during your undergrad or your master program, the most important thing for us to like learn knowledge. But since I have like an interest to conduct my own research, so I guess that’s why I want to apply to a PhD program.

JG: That’s true. Your research goals and interest in science are necessary for maintaining inspiration throughout a PhD. Dana Grieco summarizes it well.

[Dana Grieco]: Anyone who’s thinking about doing a PhD is like you need to be able to have enough excitement and wonder that it’s you’re going to be able to pull yourself back into it.

JG: But it is not easy to find your research interests or narrow your research questions. Some people choose to complete a master’s degree program or take time to work after their undergraduate degree, using that time to better develop their interests, figure out on what they want to work on for the rest of their careers. Here is Dana Grieco on her experience.

[Dana Grieco]: I had a Bachelor of Science in biology. And I knew that I was interested in marine science but didn’t know exactly what. So, after that, I kind of spent three years working in marine ecology research and environmental education. And as I started getting more and more interested in fisheries, I worked in different facets of the fishing industry as well. And I also worked in the dive industry, and I also was doing a lot of things on the side like working in the food service industry and waitressing to try to kind of make all of those things work.

And so when I knew a little bit more about what I was interested in which is really kind of this integrated system of both fisheries ecosystems and people, I hit a point where I was kind of like oh this is it this is what I want to do with my research for the rest of my life kind of this pivotal moment. When I had a point when I did, I said okay you know I would much rather do the longer research that allows me to be in charge kind of the questions I have in the research I want to do, and so a PhD really allows you to do that. Then I started looking for researchers in the US. There was a lot of searching and failed searches along the way, and a lot of times in those three years where I didn’t know what my next job would be or what I’d be doing or anything like that.

JG: Clearly, there is no singular path to a PhD. While many students feel pressured to leave their undergrad experience knowing exactly what they want to do, taking a step back can really help you home in on your specific research interests.

[Dana Grieco]: Just try to tell everyone who’s interested in getting a PhD that it’s okay to take a break, especially if that’s to explore the things that you’re interested in in a different way.

JG: Once you’ve clarified your interests and feel ready to take the next step towards the PhD, the application process itself may still prove difficult.

JG: Julia described the application process as a mystery.

[Julia Bingham]: I remember it being confusing and difficult to navigate but also exciting. I feel like the whole process overall is like a mystery even while you’re in it, and then afterwards, you kind of like oh I understand the pathway that happened, but it’s a lot of just kind of feeling it out as you go and I do remember wishing that it was a little more clear to students trying to get into Grad school.

JG: Greg described the application process as a nightmare.

[Greg Merrill]: It’s a nightmare right. um it’s tough. There’s a couple different hurdles and hoops to jump through. There’s you know the anxiety of introducing yourself and cold emailing these experts in the field whose names mean a great deal to you, and then you just have to there’s the anxiety that’s built around that, and then there’s the financial aspect of applying different places, paying for your test scores to be sent different places, you know, there’s a social hurdle of leaving another place and joining a different institution in most cases. There’s just a lot of challenges around it.

JG: I cannot agree anymore with them. The whole PhD application process is like a long and rugged marathon full of ups and downs.

JG: Among all of the difficulties, many of the interviewees said the most challenging part was that they did not have enough information and resources about how to apply to the PhD. That difficulty can be quite significant for students who are the first in their families trying to navigate through this process. Here is Greg again, on the biggest challenges he faced.

[Greg Merrill]: I think it was that it was my ignorance to the process just because of the background I grew up in. You know I grew up in this single parent low-income household as a first-generation college student, I didn’t have the same experiences and resources available to me that that my friends did. So I’m applying and I just don’t have any idea what Grad school is really about. You know I didn’t know that I needed to start building these relationships early. I didn’t realize how much it was going to cost. I didn’t really understand that in my field we weren’t just continuing like consuming knowledge, we needed to be producing it. So, I didn’t look like a good applicant, and I learned that later by applying again and over time, but that experience just came with time of being in the Academy.

JG: Dana Grieco further highlighted how important personal relationships can be during that process.

[Dana Grieco]: Get a mentor and the application process who has done it, and also, who has done it well. Ask that person if you can meet with them and ask them some questions or send them the emails that you have that you are planning on sending to potential PIs. And have someone to give you advice. It could be a student in a lab you’re interested in who you really connect with and you could be surprised that student might just want to help you find a lab that you love, whether or not it’s their lab, and they might be fine having a few emails back and forth to talk about how to best do that right. So, I would say that get over the fear that that part’s terrifying and scary and just ask people for help. Because if you’re trying to do it alone when you don’t know the process, it’s just so much harder. And it’ll make you feel so much more confident if you have someone who knows more that’s helping you.

JG: Both of these students are highlighting the importance of building relationships with people who are familiar with the application process. So, even if you don’t already have these connections, reach out to people who could be helpful, such as current PhD students in the lab you are interested in. They are often much more responsive than the PIs and can be a great resource for learning about how that lab really works. I remember when I applied for my PhD, I emailed the PhD students in labs of my interest, and their willingness to help truly surprised me, they were very helpful.

JG: Another person that you should definitely contact is whoever is the coordinator for your doctoral program of interest. They will have in depth knowledge on that school’s specific application process, can answer specific questions about funding, program requirements, and any other useful resources. Plus, answering you is part of their job, so you are likely to get an answer from a program coordinator. Rachel Lo Piccolo, is the doctoral program coordinator at the Marine Lab, and she gave me a detailed overview of the application process for a PhD at Duke University.

[Rachel Lo Piccolo]: When you’re applying for a PhD at Duke University, you’re actually applying through the Graduate School, and then once you put in an application at the Graduate School, you identify the program, and then also faculty of interest. So, in our program, you apply specifically to work with a faculty member from the beginning, there are no rotations. We also are separate from the master’s program, and so we don’t have students that are finishing the masters and rolling right into the PhD program.

So, once you identify that Duke is where you want to apply, you create an application online, and then you add your application material through the portal. And that material is going to be things like your transcripts from the previous schools that you’ve attended. Some students also upload their CV. You’re going to include a statement of purpose and, sometimes, if you will, right now, we’re not requiring them, but you can also submit your GRE. All of them are taken into consideration by the faculty when they review the applications. I would not say that any one part of them are more heavily weighted than the others, and I also want to say that it’s a really unique application process in that the students themselves are very unique. PhD students come to us from a really broad variety of backgrounds, they’re coming straight out of undergrad or master’s degree, or maybe they’ve already worked in the in the workplace and have decided to come back and get a degree. So, it may even be a program that they didn’t use or were participating in as an undergrad, it might be something that they’ve come to realize is something that they want to get more experienced at and to specialize in. So, I think that when we look at these applications, we really look at them as an individual and not necessarily comparing them to each other.

The statement of purpose is probably where we get the most information about the person themselves until we have the opportunity to actually interview them. The statement of purpose is really important to include sort of your experiences that you’ve had in education up till now and sort of some of your hopes and dreams. One thing we don’t need included in the statement of purpose is the story, although it’s very important, of when the first time you saw the ocean. We got a lot of people who still want to share with us their first experience of when they were taken to the ocean as a small child, and that is a lovely memory, and I think that everyone should cherish it and it certainly has set you on your course of your life. But it won’t serve you very well in your statement of purpose for being considered for the PhD program.

JG: Well, it is good to know you don’t need to write about how much you love the ocean in the statement of purpose. I wish I had known that sooner because, let’s just say, I have written about that in mine haha.

JG: Anyways, as Rachel mentioned, one of the first and most important parts of the application process is to identify a faculty of interest. However, while identifying and contacting the faculty you would love to work with can be quite easy, getting their attention is a different story.

[Yutian Fang]: And I guess the main challenge for me is to find the proper advisor and make self-recommendation to make your advisor believe you are the one student, I mean you are the destiny student that he or she wants. I think it’s also important that you find the right advisor which means your potential advisor should have like strong interest and appreciation over your past work and education experiences. So, if your advisor appreciates your work in the past and explicitly express his or her interest to take you in as a PhD student, then you probably will have like a larger chance to get into the program.

JG: For most of us, this is a challenging experience. If you don’t have any access or colleagues in common who are willing to introduce you, it can be tricky to get these busy researchers’ attention. That is when, again, contacting the current students in the lab may come in handy – they are often more accessible and can be a bridge between you and your potential adviser. And then obviously, you will want to learn as much as possible about someone’s research before deciding you want to work with them, but what if you don’t have access to the scientific databases? Dana Grieco shared how she navigated this particularly painful point.

[Dana Grieco]: At the time when I was applying to schools, I didn’t have access to research journals. And a lot of the links that folks put on their website about their research papers or if you go to Google Scholar to see the papers then you can’t actually look at the full PDF, right? And so some people are really good about putting the PDF in its entirety on their webpage, but I would email folks who I knew who were still in college and I had a few of my mentors and I would like have people send me, download papers, and send them to me and so that I could feel like I knew what I was talking about to approach the folks that I was reaching out to because I wanted to read their research. So I think that that was also something that gets overlooked, but for me that was extremely difficult.

I remember actually in my interview day when I was here, there was one specific paper that I had forgotten to check in with my advisor about and I kind of said you know a little bit like oh shoot I really wanted to read this paper, but I forgot to ask somebody to send it to me, so I think I’m really interested in this work as well, but I don’t know, until I had done my homework on everything else, and that paper had slipped. And I remember, he said something just like oh you know you could have emailed me, I would have sent it to you. But I was so embarrassed about emailing him, I didn’t want to bother him at the time, so I wasn’t going to email him to ask him to send me those papers. So it seems like a little thing but I think as a prospective student it’s a really big piece if you don’t have access.

JG: The barrier of access to scientific work is a subject for a whole other podcast, but something Dana said is worth emphasizing here: Most authors also hate that their work cannot be publicly available, and will be really happy to hear someone is interested in reading their work. This is a good way to start building connections, and it is a good tip not just for PhD applications, but the scientific world in general. Let me make this clear: Authors do not make a penny off those journal fees; e-mail them asking for the paper and most people will be very happy to share.

Ok, that was necessary. But back to the application process, Rachel also shared her recommendations for connecting with faculty of interest.

[Rachel Lo Piccolo]: One of the things I always tell people is it’s really a great idea to reach out to your faculty of interest, even before you apply. You know, it takes a lot of your time and energy and then there’s a cost to applying, so you want to make sure that you’re applying to the right lab that seems to be a good fit. And then to find out if that faculty member is actually taking students in the coming year. Some of the faculty are pretty good about putting that on their websites about whether they’re going to be accepting students. But otherwise, the best way is to directly contact them through email or maybe you have the opportunity of studying here and so you have already taken courses from them, or maybe you’ve seen them at a conference or they’re coming and giving a talk at your school, and you can meet them. But email is probably the most common way and you’re right, it can be very challenging to get a response from them and, and all I can say is to keep trying.

JG: Yutian definitely experienced this challenge:

[Yutian Fang]: I have to say it’s really frustrating when you refresh your inbox like I mean your email box every day and see no one replies to you and that’s what probably happened if you’re only contact with like one or two advisors per program. So like contacting as much I mean future advisors as you could.

JG: It can indeed be frustrating, and there is obviously something to be said about how this process privileges those who already have connections. But one important tip Julia shared, was to not be afraid to follow-up.

[Julia Bingham]: I’ve been in in the academic world long enough to know that, just like everyone is terrible at emails and everyone is too busy. And most of the time if you don’t get a response, it’s because the person either didn’t see it, or they forgot about it, or they just don’t have time and it’s not personal.

JG: So, if you don’t hear back from the faculty member you contacted, don’t take it personally, don’t give up, and, importantly, if you do hear back, keep in touch – build the relationship, make yourself remembered. Here is Greg on his experience.

[Greg Merrill]: I would say, this was honestly, the most important was making the connections early with potential advisors, you know, build the relationships way in advance of when you think you want to be applying.

So, like in my case, early on, it was a cold email I didn’t get a lot of replies at first, but I just I was persistent and then finally, at least for my PhD advisor, Doug, he scheduled a phone call with me, he’s like “I’ve got 15 minutes in the airport. I’m on my way from one flight to another”, and I’m like cool let’s do it. So, we had a phone chat that year, you know we I ended up not getting accepted, but it that was enough for when I contacted him again the next year for you know just reminding him like hey we chatted. He’s like oh yeah you and let’s continue that conversation. So, we ended up one of the big conferences in my field ends up ended up being in San Francisco in 2015 which wasn’t too far of a drive from where I was living at the time. So I asked Doug if you wanted to meet up for a coffee or a beer or something. And we ended up chatting then and I think that in person really like helped him solidify who I was and what I was interested in.

And so I think it was an easier process, you know, like it was faster in he was able to vouch for me when the committee was reviewing my application.

JG: I love this story because of how persistent Greg was and how passionate he was in continuing to go after his goals. It takes a long time to build relationships with potential advisors, so just go ahead and get started, and don’t let the fear of sending a cold email deter you. And as Julia mentioned, once you are in a program you will realize that emails fall through the cracks, and you’ll have to follow up with your adviser often, even after that relationship has been built!

JG: Another big challenge in the application process many of the students I talked to mentioned, was the Graduate Record Exam, or the GRE. It is a standardized test introduced in 1949 and it is an admission requirement in most United States’ schools. Dana Wright shared her experience with us.

[Dana Wright]: Taking a step back and thinking about when I first started thinking about going back to graduate school for a PhD, for me a big obstacle was the GRE score because mine had just expired right, so I really didn’t want to take it again right. So, it was just this huge kind of thing in my mind: oh man I gotta study for this, I gotta pay for this, I got to get time off work to go take it at the testing center, and you know I think it really prevented me from making that next step sooner. I thought that you would have you need to have such a high score to even be considered at the university. And the programs that I was looking at were like very well-respected programs. And so I was just like wow I really gotta I gotta ranked really high that even kind of have my application considered.

JG: The GRE is truly an exam that requires people to spend plenty of time and effort studying, not to mention the financial burden. The GRE general exam costs $205 in the United States. Many test takers end up paying for books, online practice tests, or even full courses to prepare, not to mention the cost to send scores to the schools to which you are applying, and potentially having to take the test multiple times until you get the scores you need. Moreover, many small cities do not have testing centers nearby, so some people might also have to budget for transportation or even accommodation in a different city. Simply put, it is not cheap, and it is time-consuming.

So, perhaps not surprisingly, research has found high GRE scores to be biased towards wealthy test-takers, and the scores themselves are a better predictor of socio-economic status, race, and gender, rather than they are of PhD degree completion, post-doctoral success, or quality of research. In fact, research has found that GRE scores consistently underpredicts the success of minority students, and it is a significant barrier to higher education for these groups.

JG: Greg shared how challenging it was for him.

[Greg Merrill]: For me in particular, I grew up in a low-income home, you know if you I think you got you only got so many for free to send institutions, So if you wanted to raise your chances of getting in somewhere, you had to pay extra money to send your scores, and it really added up quickly into hundreds of dollars. And you know hundreds of dollars for me meant rent for the month! You know I don’t think perhaps most people aren’t in this situation when they’re younger, they have financial support from their parents. But I was paying for everything out of pocket once I turned 18. So it was it was difficult for me to put that money towards these exams when that could have been rent or food for the month or some you know something more immediate.

JG: Increasingly, there has been more recognition of the problematic nature of standardized tests, and as Dana Wright highlights, many advisers already acknowledged good GRE scores do not necessarily translate into good science.

[Dana Wright]: So when I reached out to Andy in December again, I was really honest. I was like I don’t know if I GRE is going to be good, I don’t even know if I’m going to get into Duke with this score, I don’t know if this is like good enough for your lab. And he was really kind and saying that you know he doesn’t think that GRE scores necessarily translate to good scientists, so it’s not something that he personally would use to choose a scientist. But you know it is something that the university uses and so that is you know that was something that gave me anxiety.

JG: As Dana said, even if a specific adviser does not place high value in the GRE, a common problem is that many schools have a cut-off score, where they filter out and drop applications who did not reach the “minimum score,” without even looking at their whole application. The good news is that recently, most graduate programs at Duke University have either waived the GRE requirement or made it optional. A quick look into the Twitter hashtag #GRExit shows this is part of a larger trend among academic institutions in attempts to increase diversity and cope with the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Here is Rachel on how this decision was made in our department.

[Rachel Lo Piccolo]: When we all sort of started to feel the effects of the covid pandemic, obviously things change in education, and one of the things we had to take a look at was how we were going to be admitting our students and what we would be expecting from them. And one of the things that across the university as Duke as a whole started to have the conversations about whether we felt that the GRE were going to be as useful. It’s a conversation that’s been going on for a long time, to be honest, and it’s been something that our program as the faculty collectively have spoken about as to whether we would like to try to not have the GRE be a part of the indicator as to the type of student that we’d be admitting. The other concern was that accessibility of taking the GRE. As we all move to a remote platform, the ability to take the GRE and have them submitted would be more challenging for a lot of students, particularly international students. And to keep it a more level playing field, we decided to just make them optional; and we’re continuing to make them optional as we sort of continue this experiment, as to whether or not we need those to use as an indicator as to the type of students that we are admitting.

JG: While making the GRE optional is certainly a step in the right direction, according to Julie Posselt, a professor, and the author of “Inside Graduate Admissions: Merit, Diversity, and Faculty Gatekeeping,” this is not a long-term fix to the diversity problem. According to her, quote, “What it almost always does is increase the college’s image regarding selectivity because more people apply and those who do report scores tend to have higher ones” end quote.

JG: When I talked to Dana Grieco, she expressed similar concerns.

[Dana Grieco]: I think that to me, GRE optional is kind of one of those tricky situations if somebody can submit that GRE score then it’s more likely that folks from privileged backgrounds, and who grew up in the United States might have an easier time taking the standardized tests since it’s like all of the testing that folks do growing up, would do well on the GRE, and would be able to pay for it and take it. So it’s still kind of if it’s GRE optional right, we’re still allowing this bias to come in where we say that getting a score on the GRE that is good makes you a better candidate.

JG: Rachel, on the other hand, reassured me that that is not the case, and that the goal is to eventually find better ways to assess a candidate’s abilities.

[Rachel Lo Piccolo]: GRE score, while it is being not being required and it’s optional, we are not using that as part of the evaluation, because we are making it optional so wouldn’t be fair to just because of the students submitted them that we would. But again, the GRE score is a real snapshot sometimes, and I think what we’re finding is that the GRE scores can be better to indicate some types of students’ abilities and not for others. Not everybody is a great test taker and that doesn’t necessarily equate to them not being a great scientist or being able to ask great questions and come up with hypothesis to test. And so, if we can find other ways within the actual application process to evaluate students, it may not be as necessary for us to include GRE even into the future. And then, particularly to if you think about international students, if English is not your first language, the GRE may also pose to be much more challenging and not be very reflective of the type of student that you really truly have the ability to be.

JG: Similarly, Julia pointed out that the skills most needed in a PhD are not the ones measured by the GRE.

[Julia Bingham]: Like in Grad school what’s important is your critical thinking, your problem solving, your creativity, your teamwork and collaboration skills with your peers, and your writing skills and those are all things that you can also hone in Grad school, but you don’t necessarily have to have those perfected before entering a Graduate program.

JG: And Greg summarizes many of the sentiments shared with me.

[Greg Merrill]: I really applaud the current waiver of it, and I really hope that brings down the barrier and raises some of the equity in the application process to bring in promising new students.

JG: That is certainly a hope we all share, and we welcome the GRE waiver as an important step forward. Unfortunately, the GRE is not the only significant cost during a PhD application. The application fees themselves are also expensive, which can prove prohibitive for some students. Here is Greg again.

[Greg Merrill]: You know I think to some of my friends that applied right out of undergrad, and they would apply to like 12 schools, and I’m like holy cow that’s like 1500 bucks once you wrap in all the different fees. And so, for me, I think I remember right I did like four the first round, three the second round which was like exactly the number of free GRE scores they would send, so I like didn’t pay any extra but I’m still paying the application fees to those to schools.

JG: Application fees are an important consideration, and also, constrained Julia in how many schools she decided to apply to.

[Julia Bingham]: For me, I definitely couldn’t have afforded to apply to more schools. I think for a lot of folks that means that just the process of applying and getting to Grad school can be a really big risk. And I definitely think that the cost of just applying is kind of ridiculous. I understand why there is some fee associated with these processes, but I think that burden could be placed on you know Federal education system potentially, or there you know you don’t have to make potential students pay out their entire pocket for the chance that they might possibly maybe get accepted and then be able to go to Grad school.

JG: I hate that so much is about money, but unfortunately, application fees and the cost of taking GRE are not the only important financial considerations. In considering different programs, you should pay close attention to the funding available. Does the doctoral program offer fellowships or assistantships? Do you need to apply for external funding to support yourself? Are you expected to cover your own expenses? Do you get health insurance? These are the next five years of your life, make sure you get a clear picture of your funding situation.

In our case here at the Marine Lab, we have guaranteed funding for five years of the program, through a combination of fellowships, scholarships, and teaching assistantships. They have a complicated system for deciding how many students can be taken every year on school funds, and which faculty has priority on any given year. What that means is that even if you find an adviser that wants you, you might still not get in, unless they have their own way of funding you, or you find external funding.

For domestic prospective students, the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program, aka NSF GRFP, is a great potential funding opportunity to look into, and many of our colleagues here at the Marine Lab have successfully secured funding through NSF. Applying for external funding can not only increase your chances of getting into a program, but can also give you more freedom to pursue your own interests.

Here’s what Dana Wright had to say about this.

[Dana Wright]: One of the pieces of advice I was given by many colleagues and friends was like, especially because I had a project in mind that I wanted to do, so they’re like you need to arrive with your own money; because if you don’t then you might get put on a different project that your advisor has money for or just kind of whatever project that you happen to get funding for that kind of might force you to not do the research that you want to do.

JG: So far, we talked about finding interests, contacting with faculty of interests, taking GRE, and financial issues — these are some of the common challenges to most PhD applicants. While facing with these difficulties, we all have our own insecurities to overcome. To Greg, it was a struggle about how much to share of his own identity.

[Greg Merrill]: One of the other things that I really struggled with was, you know, different intersections of my identity, whether or not I would mention these in the application process. When I was applying to undergrad, I was so adamant that I wouldn’t say that I was a gay man because I didn’t want to get accepted to a university just because I was gay, I wanted to prove that I had, you know, the knowledge, or you know, the intelligence to do it. So, I really struggle with Grad school, whether or not that was a stupid notion and whether I should just be proud about who I was and what that has meant for me. So that was more of like an internal struggle, and I have no idea in which way it affected the process. But I did end up saying it in my applications.

JG: To Dana Wright, her concerns were about returning to academia after working for five years.

[Dana Wright]: I definitely felt like oh man I’m going to be so much older than everybody else and everybody’s going to be so much smarter than me just because I was like the students are going to have skill sets and coding and mapping and all this stuff that like I don’t have because I wasn’t at school when that was being taught, and then I was in the workforce when that you know I just was I didn’t learn those things. I was worried I wouldn’t have the energy and the motivation that I might have had if I was five years younger, you know, I was just a little worried that I was going to get burnt out or that I just wasn’t going to have the stamina to do the hours that sometimes a PhD program requires.

JG: But just like in Greg’s case, Dana found her insecurities were appeased by a welcoming and stimulating environment.

[Dana Wright]: Yeah, I mean surprised myself that that’s not true. And yeah, and also I feel just so lucky that my cohort and the community was supportive of me you know. And we’ve all really helped each other with the skills that we’ve had. And I feel so lucky that I get to learn from them, and you know I’d like to think that they learned a little bit from me. So, there is a give and take like we all have value with our lived experiences. So again, don’t be afraid, don’t let that be the thing that holds you back because it’s worth it, I think it’s worth it.

JG: I love that. Don’t be afraid to jump out of your comfort zone, let what’s deep inside your heart guide you. Easier said than done, right? Well, Yutian suggests how one can manage to go through all that.

[Yutian Fang]: It’s also important that you have like proper support during this process from your friends or family, I mean like the mental support. And I hope everyone who listen to this podcast can find your proper support during this process, just try the best as you can, and don’t worry too much about the final result, because I think everyone will have their own way to sort out at the end.

JG: Yeah, I think it’s important to remember, that while applying to a PhD program can be a challenging process, it can also be one through which you learn a lot, build connections, and develop interests.

[‘Oyster Waltz’ theme song]

JG: So, to re-cap, the shared wisdom from our PhD students suggests that, if you are interested in applying for a PhD program, you should: Number one: figure out the reasons why you want a PhD. Having a strong motivation will keep you sane throughout your journey. Number two: build relationships. Reach out to people who have done this before, reach out to students at the lab you are interested in, reach out to the advisor you’re interested in, reach out to the program coordinator, reach out to anyone you can. Don’t be afraid to follow back and keep in touch. Number three: there are many financial considerations to be made. Learn about how the programs you are interested in would fund you, and make sure you budget for any tests you need to take, application fees, and whatever else. Number four: look into external funding. They increase your chances and potentially give you more freedom. Number five: don’t let personal insecurities prevent you from trying. Dive in! And bonus tip, don’t forget to take care of your mental health and find a support system to help you through the process.

JG: Before we wrap up, I want to say a huge thank you to all of the interviewees for sharing their journeys to the PhD with me. This episode could never do justice to all of their fantastic stories. You can learn more about each one of them on our website, at sites.nicholas.duke.edu/seastheday/

JG: We hope you enjoyed this episode of PhDeep, a series where we explore the lives of PhD students. This podcast was written and produced by me, Junyao Gu. Rafa Lobo co-wrote the script, and Rebecca Horan edited and reviewed it. Our theme song is by Joe Morton, our artwork is by Stephanie Hillsgrove. Follow us on Instagram and twitter @seasthedaypod. Thanks for listening and see you next time!

[theme song fades away]

END OF TRANSCRIPT

REFERENCES

Anderson, Nick and Svrluga, Susan (2018). What’s the Trump effect on international enrollment? Report finds new foreign students are dwindling. The Washington Post, November 13, 2018. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/report-finds-new-foreign-students-are-dwindling-renewing-questions-about-possible-trump-effect-on-enrollment/2018/11/12/7b1bac92-e68b-11e8-a939-9469f1166f9d_story.html

De Los Reyes, A., & Uddin, L. Q. (2021). Revising evaluation metrics for graduate admissions and faculty advancement to dismantle privilege. Nature Neuroscience, 24(6), 755-758. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-021-00836-2

Duke University, (2021). All Departments: PhD and Masters Admissions and Enrollment Statistics. October, 2021. Available at: https://gradschool.duke.edu/about/statistics/all-departments-phd-and-masters-admissions-and-enrollment-statistics

ETS (2021). Fees for GRE® Tests and Related Services. July 1, 2021. Available at: https://www.ets.org/gre/revised_general/register/fees

Ilana Kowarski (2019). How Long Does It Take to Get a Ph.D. Degree? Earning a Ph.D. from a U.S. grad school typically requires nearly six years, federal statistics show. U.S. News & World Report, August 12m 2019. Available at: https://www.usnews.com/education/best-graduate-schools/articles/2019-08-12/how-long-does-it-take-to-get-a-phd-degree-and-should-you-get-one

Miller, C. (2014). COLUMN: A test that fails. Nature, 510(7504), 303-304. https://doi.org/10.1038/nj7504-303a

National Science Foundation (2021). About GRFP. Available at: https://www.nsfgrfp.org/resources/about-grfp/