On this episode, the host, Rafaella Lobo, talks to five current and former students, as well as a faculty member, about their experiences leaving their home countries to pursue higher education in the US.

Listen Now

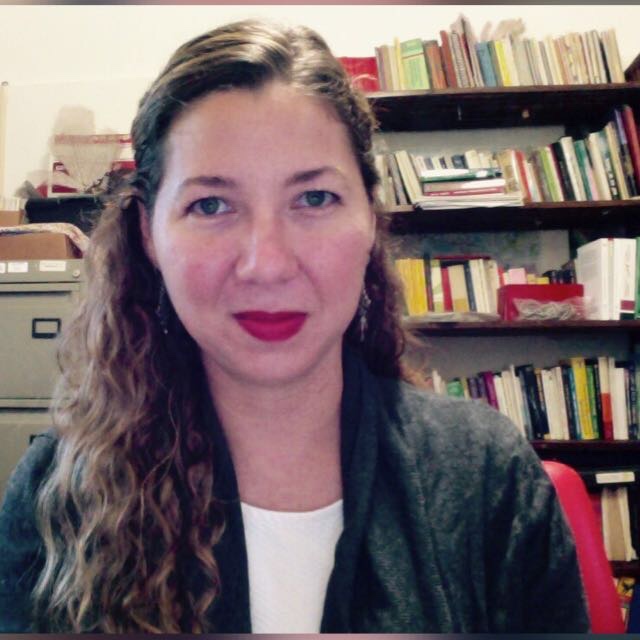

Host

Rafaella Lobo, 3rd year PhD student at Dr. Lisa Campbell’s lab

Rafa is originally from Brazil, where she got a bachelor’s degree in International Relations from PUC-GO. She came to the US in 2014, to get her Master’s in Political Science at the University of Central Florida. In 2016 she was hired by the Duke Marine Lab to do pilot whale photo ID at Dr. Andrew Read’s lab, when her podcast addiction started. She began her PhD in 2018 under Dr. Campbell’s advising, and they have been talking about launching a podcast ever since. She has volunteered, interned and worked with marine/environmental institutions, such as the Hubbs-SeaWorld Research Institute, the Sarasota Dolphin Research Program, and the World Wildlife Fund. She’s been the Alexandra Cousteau Environment and Global Climate Change Fellow, and the Duke Global Policy Fellow. Her PhD research focuses on international governance for biodiversity conservation, particularly at the intersection of North-South issues.

Twitter: @LellaLobo

Interviewees

Dr. Xavier Basurto, Associate Professor of Sustainability Science at the Nicholas School of the Environment and director of the Coasts and Commons Co-Laboratory at Duke University.

His expertise lies in the governance of the commons, particularly in the context of inshore fisheries. He has developed large scale collaborations between academia, practitioners, and fishing organizations to co-design studies aimed at diagnosing the performance of different types of fishing organizations. He is also interested on how biophysical factors affects the performance of diverse governance arrangements. Xavier has published more than 60 articles in a diversity of outlets and has been funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation and a diversity of philanthropic organizations based in the U.S. and Europe. Currently, Xavier is collaborating with FAO in in the design and implementation of the methodologies for two main projects: Illuminating Hidden Harvests and the mapping of global fishing organizations.

Paula Chávez, Conservation Officer, Fondo Mexicano para la Conservación de la Naturaleza.

Paula is a Colombian marine conservationist with a B.S degree in Biology from the Universidad de los Andes in Bogotá, Colombia. While in Colombia, she worked as the Staff Biologist at the CDMB, a state environmental agency. Afterward, she pursued a Master in Environmental Management with a focus in Coastal Environmental Management at Duke University where she worked as a research assistant. Before moving to Mexico, Paula interned at NRDC’s Oceans Program in San Francisco, CA, and collaborated with the Eastern Tropical Pacific Seascape program at Conservation International. Paula joined the Mexican Fund for the Conservation of Nature (FMCN) in 2018 where her primary responsibilities are supervising marine conservation projects supported; reporting the program’s results to donors; supporting in project design and grant-writing to maintain the financial capital for marine conservation in Northwest Mexico, and coordinating marine monitoring projects in collaboration with the National Commission for the Knowledge and Use of Biodiversity. Paula is currently based in La Paz, BCS, México where she is constantly amazed by the beautiful land and seascapes, and enjoys her time by walking her dog Ramón, practicing some yoga, and going to the beach.

Instagram: @paulaachavezc

Junyao Gu, 2nd year PhD student at Dr. Zackary Johnson’s lab

Junyao grew up in a coastal city named Lianyungang in Jiangsu Province, China. She received a Bachelor of Science degree in Environmental Science and a Bachelor of Laws degree in Law from Jilin University, China in 2017. She graduated with a Master’s degree from the Department of Environmental Health and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University in 2019, where she found her deep love for exploring the tiny mysterious microbial world and had a wonderful time doing research in Dr. Sarah Preheim’s lab. She joined Dr. Zackary Johnson’s research group as a Ph.D. student in 2019 and she currently studies the microbial ecology and metagenomics of marine phytoplankton.

Instagram: @gu_junyao

Dr. Crisol Méndez-Medina, Post-Doc at the Coasts and Commons Co-Lab (Dr. Xavier Basurto)

Crisol’sbackground is in Sociology with a minor in Latin-American studies. She holds a Doctorate in Ecology and Sustainable Development from El Colegio de la Frontera Sur (Mexico). She is conservation scientist and institutional scholar who works at the interfaceof ecology, sociology, resource management, and policy to solve real-world natural resource management problem. She is a Fullbright Scholar (2017-2018) and MSC Fellow (2016). Currently she coordinates a participatory action research project in Mexico, working collaboratively with different stakeholders, NGOs, fishers, and scientists: The National Plan to Strengthen the Governance of Fishing Organizations.

Twitter: @CrisolMM

Dr. Phillip J. Turner, Science-Policy Consultant

Phil is an early career researcher with experience in deep-sea mining, deep-sea ecosystem services and ocean governance. Phil graduated from Duke University in 2019 with a PhD in Marine Science and Conservation. His PhD research explored i) the ecology of methane seeps on the US Atlantic margin and interactions with the deep-sea red crab fishery; ii) the ecology of hydrothermal vents and the potential impact of deep-sea mining on functional diversity; and iii) the cultural significance of the Atlantic seabed in the context of the transatlantic slave trade and the importance of memorializing those who died during their Middle Passage prior to commercial mining. Since graduating from Duke Phil has been working as a science-policy consultant for Seascape Consultants Ltd (United Kingdom). In this role he is helping to ensure that research generated by the EU funded Horizon-2020 projects ATLAS and iAtlantic are communicated to decision makers and used to inform on-going policy discussions. You can find all of his publications to date here.

Twitter: @deepsea_phil

LinkedIn: www.linkedin.com/in/drphillipturner

View Transcript

TRANSCRIPT

Seas the Day – PhDeep – Episode 13

Finding the people in the politics: International students in the US.

*Various news clips on international student ban news.

[Lagoon, by Drama for Yamaha playing in the background]

Rafaella Lobo: On July 6th, during a global pandemic, the Trump administration announced what became known as the international student ban: the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) ruling, lifted the COVID19 exemptions put in place in March, so that international students not enrolled in classes, or enrolled in online classes only, would now not be allowed to remain in the country. The ruling was met with immediate backlash from some in the news media, trendy hashtags on Twitter, and strong opposition by academics across the country. Only two days later, Harvard University and MIT, joined by over 200 schools and universities, including Duke, sued the Trump administration in federal court. Against this backdrop of opposition, the ruling was rescinded before a judge even had to look at it.

As an international student myself, I got caught up in the Tweet storm in the aftermath of Trump’s proposed student ban. I retweeted many of the arguments in favor of international students – which are mostly economic and political, and I’ll review them for you soon – but after my initial fears for my own status and that of international students more generally, I found myself questioning those same arguments. Not for whether or not they are true, but for how they represent and characterize international students, the way they value them. Or, us. The turning point for me? A Tweet by @AcademicChatter that read “International students shouldn’t be protected because ‘their labs/departments will produce less research without them’, but because they’re *PEOPLE*.”

[song ends]

People – ALL CAPS.

[‘Oyster Waltz’ theme song]

You are listening to Seas the Day and in this episode of PhDeep, I’ll introduce you to some of those people. I spoke with international students pursuing a graduate degree at the Duke University Marine Lab, and you hear about the joys, challenges, rewards, sacrifices and expectations that come with leaving everything behind in a home country to pursue a better education in the US. I am your host, Rafaella Lobo, but as an international student myself, in today’s episode I’ll be more than a simple narrator. Welcome, to Seas the Day

[theme song ends]

Okay, let’s start with the arguments for and against international students that the proposed international student ban sparked.

I don’t want to give too much airtime to arguments in favor of the ban. You’ve likely heard them before.

[Morning Movement, by Kathleen Martin playing in the background]

International students take American jobs, they’re potential terrorists, they’re the initial link in chain migration… In this way, the international student ban reflects the xenophobia underlying the Trump administration’s approach to immigration in general.

[song ends]

Enough said.

Those opposing the ban saw it as an attempt to pressure universities to reopen during the pandemic. But, if implemented, opponents pointed to the consequences for students. Many international students lack reliable internet access in their home countries, or the freedom to use it. Chinese students, for example, can’t use G suite. Participating in remote classes across different time zones also meant some would have to be up at 2, 3 am to take online classes, or that professors would have to offer multiple sessions of the same class to accommodate their globally distributed students. In the worst cases, some students might not have homes to go back to, due to conflict in their home countries, or to COVID related travel and reentry restrictions.

[Beat Poets, by the Snake Oil Salesman playing in the background]

But a different type of argument quickly emerged, one that focused not on the costs to international students forced to return home, but the costs to the US in sending them there.

The first set of costs are economic. Numbers from the Association of International Educators on the economic value of international students were brought up often. The “International Student Economic Value Tool” uses expenses and incomes to calculate the ‘value’ of international students, and then aggregates this to the population of international students in the US. Do you wanna know how much that is? Well, for the 2019-2020 academic year, international students contributed almost 39 billion dollars and supported over 415 thousand jobs to the U.S. economy. That’s right, economically, international students are a benefit to the US.

[cash register sound, + song ends]

There are also concerns about hidden contributions to the economy through international student participation in research. This is particularly true of graduate students, and the initial tweet I mentioned was responsive to this argument, specifically. Concerns that valuable researchers might stay and take US jobs were countered by pointing to the many Silicon Valley tech geniuses and other start up entrepreneurs who came from other countries as students. That they stayed and started their businesses in the US is a benefit. The same goes for the ones who invent vaccines, or become Nobel laureates – you know there is an additional prestige benefit to the US serving as their host country.

Interesting political arguments also emerged. International students are portrayed as tools for facilitating foreign policy diplomacy; the idea is that they’ll be indoctrinated with democratic ideals during their time in the US, and, when they go back home and reach positions of power, they’ll be, at the very least, more amenable to maintaining a positive relationship with the US. While in the US, they are a bonus to institutions seeking to increase their diversity and inclusion, and they can teach American students about the importance of diversity.

All of these arguments may be true on some level, so what’s my problem? Well, it’s not actually my problem, it’s one that was pointed out by Yao and Viggiano in their article published in 2019 called “Interest Convergence and the Commodification of International Students and Scholars in the United States”.

[Children’s Joy by Borrtex playing in the background]

Basically, they show that these types of instrumental arguments ‘commodify’ international students, equating their value with their economic and political contributions to the US. Even the arguments about diversity are problematic: As Yao and Viggiano put it: “The diversity rationale promotes diversity for the purpose of advantaging the dominant and powerful group, rather than acknowledging that the disempowered are worthy of equitable treatment in their own right” (p.95), so “the personal lives of scholars are only considered in terms of their influence on knowledge production for the interests of the United States” (p.100).

So, even though these instrumental arguments are possibly necessary in the current bipartisan US political landscape, and in a neoliberal political economy that prioritizes economic rationality, they are still morally problematic. In assessing the worth of an international student only in terms of US interests, we fail to recognize their – and I guess our I mean ‘our’ –humanity: we are people. Again, the critique extends to immigrants more generally, but since the immigrants I know are mostly students, and this is a series about life as a PhD student after all, that’s who you’ll hear from today. Let’s get started.

[song ends]

RL: First things first. As you can probably tell, the topic of international students living in the US is one that is very near and dear to my heart. I was born and raised in Brazil, but I’ve had quite a lot of experience as an international student myself.

[‘Oyster Waltz’ theme song playing in the background]

RL: For this episode, I interviewed people who either are, or have been international students themselves. I interviewed a former Master’s student,

[Paula] My name is Paula Chavez I am from Colombia, but I currently work in Mexico.

RL: A recent doctoral graduate,

[Phill] I’m Phillip Turner, I’m from the UK, currently based in Southampton, which I guess is most famous because the Titanic left from there…

RL: A current postdoc,

[Crisol] Hi Rafa, I’m Crisol Mendez-Medina and I’m from Mexico, from small town in the South Pacific, Zihuatanejo.

RL: Also from Mexico, I talked to a current faculty member who came to the US first as a graduate student

[Xavier] My complete name is Xavier Basurto Guillermo, we use two last names in Latin America, as you know

RL: And of course, since this is PhDeep, I also talked to current PhD students:

[Junyao] So my name is Junyao Gu and I grew up in the southern part of China, a city near Shanghai.

[Betta] I am Elisabetta Menini, everybody knows me as Betta, and I’m from Italy. I’m from Montegrotto Terme.

RL: As I talked to these people, one of the most interesting things was to realize how similar most of our experiences have been. As they described the challenges and the joys of being an international student in the US, more often than not I could feel and understand exactly what they meant. But there was one question in particular that resonated across all of the interviews. Every time I asked one of them what they missed the most from home, the answers were all very similar. Can you guess what it is?

[Crisol] Well, I miss the food. Badly.

[Junyao] First is just family, friends. And secondly, I think food.

[theme song ends]

RL: Again and again, most answers went to some variation of family, friends, and food – some of the essential things that make us human. We all need to eat, and we all come from someone, at a very basic level. Some, like Phill and I, feel guilty about thinking of food first, but we just can’t help ourselves.

[Phill] My mind instantly went to food related… And then I was definitely like ‘oh I should bump the fiancé… Yeah just meat pies… like decent cheese that doesn’t cost the earth that really hit me…

RL: We miss family independent of food – of course – but these things are closely linked. Junyao explains it best:

[Junyao] It’s so funny, when I call my mother, and my mom say ‘why you miss me so much?’ I say ‘why, I was hungry. I miss you so much mommy cannot imagine how I miss you.’

RL: I feel you Junyao. We can Facetime our families, but we can’t eat the amazing food they’re cooking thousands of kilometers away. Yes, I said kilometers, because this is an international student podcast and we’ll never understand why Americans use miles.

RL: Anyways, this whole food conversation gets to a new level when I talk to Elisabetta Menini, or Betta to us. She is an Italian PhD student, and she fits into every food stereotype you might have in mind about Italians, seriously. She has cooked for boat crews, she cooked for my wedding, and during the height of the pandemic, she started a YouTube channel called “With Betta is Better” to teach us her amazing recipes. When I asked her what she missed most, I was sure she was also going to say food, in general. But just like our other European student, she said:

[Betta] Family, friends and the fresh cheese. The food, I can cook the food like I can cook, and if I miss like a certain type of sauce or pasta or whatever, I usually can find most of ingredients like… and recreate it.

RL: When I first met Betta, she had just come from Europe, and her luggage was filled with coffee and parmigiano cheese (which she wants me to make sure you know is very different than parmesan cheese). She tells me the story of when she first went to LIDL, a European chain grocery store, and found her favorite brand of pasta.

[Bouncy Gypsy Beats by John Bartmann playing in the background]

[Betta] Yes. Actually, I was with Joe Fader. And we were like roommates so he said I am going to LIDL, do you want to come with me? and I was like, oh, yes, absolutely. Yes. Yes. Let’s go because LIDL is European and we have it here. And as soon as like I arrived and I saw like one of the best… better! Better type of pasta that I usually can find at the supermarket. I think I bought like I don’t know if three, five kilos of that… I think… is like, I don’t know, I it was just kind of like two of that, two of that, three of that, three of that… Okay, let’s go and Joe was like what are you doing with all that pasta? I was like, I’m going to eat it! Haha I was like, there is a sale, and it’s a good brand…

[song ends]

RL: Food availability and affordability are the two main challenges for international students. A 2019 survey of international students across US universities found that 42% of students find food from their home countries too expensive, and 49% say there aren’t options at all. I thought that number was actually really low, and I think this is skewed because of how the question is formulated. For example, there are a handful of Chinese restaurants around here, but when I asked Junyao about them…

[Junyao] hahahaha… (pause…) Oh, I think… They are ok… But not very… traditional Chinese food… Haha

RL: And as a Latina, I always feel like the “Hispanic” section at the supermarket is actually a “Mexican” section, so I asked Crisol her thoughts on food availability here.

[Crisol] Well, what you can find here is a Tex-Mex version. It’s not Mexican food. I mean it is Mexican food because it’s created by Mexicans living here in United States, but it’s not the food that I grew up with. Like the food. I mean, I’m from the center South, so I grew up eating like a lot of herbs and plants and flowers and I cannot find them here.

RL: I want to stress that we are not saying that American Chinese and Mexican restaurants are necessarily bad. We are just saying they don’t offer what we miss.

[Crisol] Yeah I miss… But it’s not just about the ingredients it’s like going to the street market, and finding like… this… it’s a big variety of like fruits, and veggies fresh, the flavor. I mean, they are the same fruit, but they don’t taste even close and it’s not just about the food itself, it’s, our culture it’s very attached to the preparation of the meals. Because you know the Latina woman like we grew up on the kitchen and I remember being cooking on the like on the kitchen and my dad being there talking with us all the time.

RL: Crisol’s transition from food to family speaks to the crux of the problem here. We miss the food, but more importantly we miss the social experience of food that, until coming to the US, we took for granted

[Phill] Yeah, there’s some food you really do miss your home surroundings, and that’s always what gets you, I think.

RL: Ok so, another question that I asked was “what are the main challenges of being an international student?” Cultural and language barriers ranked high, and again, really resonated with me. When I first started my Masters, I had to look up the meaning of so many words, and that really slowed me down, I often had to attend the university’s writing center to get help with assignments. And I was coming from a decent starting point. Still, academic writing is a whole different beast, and I can only imagine how it feels to students who come with less fluent language skills. Here’s what Xavier told me about when he first came to the US:

[Xavier] It was so exhausting, that first year. Yeah it yeah it is exhausting like, now I think in English, of course, but at the beginning was like, you know, trying to communicate and trying to just be really focused listening to the professor and writing notes – do I write them in English and Spanish? I write them in both? No no no… like, it was literally sink or swim…

RL: This sink or swim feeling? VERY REAL. International students are often required to maintain a full credit course load, and have strict visa deadlines, in a way that there is not much flexibility on how and when they can go through their program. Graduate school is already challenging by default, so ‘being slower’ – slower to read, slower to write, missing content from lectures, all that adds a great deal of stress. In fact, 59% of international students across the US think the amount of time spent outside of class on schoolwork and activities related to their academic program is more than they expected it to be. And let me tell you, we expect it to be hard! Here’s Junyao on her experience:

[Junyao] I really found it was hard for me, when I began my first week in the semester at Johns Hopkins, because I remember I wanted to take the chemistry class. I know these chemical elements and compounds in Chinese name. But it’s hard for me to relate their names with the English name… So I found, a little harder to keep up with the class, keep up with what the professor say. And this feeling is not very good because you see all of your classmates, they, they know their names, they say, they understand what the professor say, but only you there… You feel so lonely, and so at loss… But I soon quickly change my learning style. I remember the first weekend I didn’t, I didn’t sleep the whole night I just read the book of that class. The recommended book, I finished I think up to 300 pages, I didn’t sleep for the day and night, and I just searched and write down every words I come up with that I’m not… know I’m not familiar with…

RL: Junyao says this feeling has gotten a lot better, and academically, she feels safer now. But she mentions it’s not just language barriers per se, but the cultural use of language that still gets her.

[Junyao]: Haha Yes, I think become much better, but sometimes you yeah you still feel at loss… Is probably when… say when you hear some local or say the national jokes or something. When they talk about some jokes. They, they know what they mean. But you don’t know when the… you don’t know why they start to laugh…

RL: Cultural and language barriers often go hand in hand. According to that 2019 survey I mentioned, “Students may arrive in the U.S. with outstanding academic English, only to find that they cannot understand the idiomatic English used both in and out of the classroom. Further, it may be challenging to grasp cultural expectations of when and with whom it is appropriate to use these different forms of verbal communication” (p.18).

RL: As significant as language and cultural barriers are, they are far from being the only ones. Here’s Junyao again:

[Junyao] I found is challenging for me to, say have a house, set up internet, so all this living, small lifestyle (…) To say, have your bank, credit card or something… and maybe buy your car, buy the insurance (…) Although they are very tiny, not many… it’s nothing difficult to some people, but… I think it took me some time.

RL: I cannot overemphasize how significant these “tiny” things are. They are indeed small, daily tasks that most people don’t think twice about. But when you arrive at a place where you don’t have any friends or family, and aren’t familiar with, well, anything really, it can be very overwhelming. And before anyone suggests that “we should just arrive earlier”, we can’t. There are strict timelines for international students entering the country: No more than 30 days before the program starts.

[Safari Time, by John Bartmann playing in the background]

RL: So, we have to find a place to live, set up electricity and internet, get a phone, buy furniture and living essentials, figure out how to move around, present proper documentation to visa services, figure out how the school online system works, where to get ID cards, how to open a bank account… Am I buying a car? If yes, do I need a new driver’s license? How in the world do I go about buying a car?

[Phill] Yeah, I remember being a bit overwhelmed at the beginning like trying to get everything and get settled and get sorted… I remember I almost had a break down in Bed, Bath and Beyond, it like hit me when I’d already made so many decisions that day and like spending the money. I was trying to sort life out…Well the shop assistant was really helpful but she kept, it was just us facing this wall of pillows and she was like ‘are you a front sleeper, are you a back sleeper, are you a side sleeper, like which pillow will suit you best’. And hahah yeah I was like I can’t make any more decisions today, it’s too much.

[end song]

RL: Yes, even pillow shopping can get overwhelming. Not to mention, that in order to make one decision, you often need to have already made a previous decision. You need a phone number to set up almost everything, but since you don’t have anyone to call yet – you don’t know anyone – it’s often not the first thing you think of. For me, one of the toughest hurdles at the beginning was finding a place to live, which I had to do from outside of the US, but I wanted to know I had a place to sleep. Then I arrived, jet legged, and they tell me, that because I have no US credit, I need to make a deposit to cover two months of rent. Ok, cool, can I pay with my Brazilian credit card? Nope. You need a check or a money order. Well, I clearly haven’t had time to think of bank account yet, so… What in the world are money orders and how can I get one? Not having US credit gets us EVERY.TIME.

[Phill] Like, credit score? And general life tasks that you need to do… So, I guess the worst thing was trying to get a mobile phone contract was pretty tricky at the beginning, because you don’t have a credit score, they don’t trust you for anybody, regardless of whether you show them how, like, you have some savings in UK pounds, it doesn’t matter. And I remember having to cough up at the beginning like $500 deposit on a contract to get a monthly contract on a mobile phone.

RL: Betta also had an experience that is worth sharing in full. So, for context, where we are in rural Eastern North Carolina, it is pretty impossible to move around without a car. Public transportation was actually mentioned by Junyao as one of the things she misses the most. But anyways, because of that, buying a car is often one of the first things we have to do when we move here.

[Happy Boccherini, by Lanark playing in the background]

[Betta] The car. I was like, Oh, I’m gonna like lease a car because I’m gonna stay here for a little bit, so instead of buying an old car that it might die in six months because it had like so many problems, etc. I was like, I don’t want to do that. I’m just gonna lease one that is going to be new, It’s gonna be cool, blah, blah, blah. I was like excited to get a new car was like Yes. Nice. This is a good. This is a good deal. I was like, informing myself, and there was a lease for three years, I was like, ah this is perfect, whatever, then I went to the dealer. The car dealer and it was like checking all the car like oh yeah nice. And at the time, like the time (?) Okay. So show me that and that and your credit, and I was like, what do you mean your credit? US credit. And I say, what are they? Like what is US credit? It is a credit card? I have a credit card, look this is my credit card. And he was like No, no, no. Your US credit. I was like, I don’t know who you’re talking about. So they checked for me. And of course, since I’m Italian, I discovered that I didn’t have any US credit. Which means actually being like I don’t know, they, I don’t have any debt, actually like most of US people have debt. So, if you have debt and you are from US, you are good. You can buy a car with a lease. But if you’re not, if you don’t have any debt, but you are foreign, you cannot lease the car. So that’s what I discovered, and I discovered in that way. And so at that point it was like, Oh my God, yes it blew my mind completely, and I was like okay well I guess I just have to buy one. So I bought a car, finally.

[song ends]

RL: What I love about this story, is that you can see Betta did the research on her options. I remember following her quest to buy a car for months, and she was definitely informing herself, she learned all about leases. But she didn’t know about credit ratings. So, even when you know what you’re looking for, it can be very tricky to navigate such unfamiliar systems. Here’s Phill on what he called “the hell of the US tax system”

[Phill] I just don’t understand how such a developed country can have such a complicated system. In the US there’s so many forms to fill out. There’s such a process of paying tax out of your estimating how much tax you have to pay and paying out of your paycheck, and then going through the process of getting it reinvested into your bank account… And I’ve made… last, it was the year before last, I made one mistake, I put a number in the wrong box and the system decided that I haven’t paid any tax. At all. So, I had to pay again. And then get reimbursed the full amount plus the amount that I was meant to be reimbursed anyway.

RL: I asked him how he found out he had made a mistake.

[Phill] Because I got very scary letters.

RL: I can only imagine how scary those letters were. Obviously, the tax system is complicated for everyone, but for us, there is always the fear of deportation. So, we become a little paranoid trying to learn about all the requirements of being a foreigner living in America. And there are many.

Here’s Betta again on how student visas have strict requirements on what you’re allowed to do, even if it’s related to your program:

[Betta] The bureaucracy is very annoying is like you have so many rules and you have to declare every everything that you do. There was like a time while I was going with my professor to workshop outside and I have to ask the permission to go for international travel and I suppose to not fly until I don’t have the permission. So, it was very like stressful because they were not answering or they were not approving and so you had to call them to solicit like more and more email, whatever. It was very stressful. So yeah, bureaucracy that was a major with visa and there is a lot, that it’s something that is, yeah, you have to consider you have always to remember that you have to do an extra thing for that.

RL: There is ALWAYS an extra step, an extra hurdle, possibly – very likely – an extra fee. I cannot tell you how many times I couldn’t take on a dream internship, or a summer job, or even do volunteer work. That’s right. The fear of us “taking American jobs” is so great that we can’t even work for free unless it’s directly related to our program, and we go through the proper, and expensive, paperwork. And to be honest, sometimes it’s just hard to navigate all these rules, regardless of whether it’s related to our visas or not. And if it’s hard to navigate in a place like Duke, where there are many international students and great staff members dedicated to supporting us, I can only imagine how difficult it is for students at institutions with less support. Fear of accidently breaking the rules is very real.

[Crisol] I’m always worried about the police and not breaking any rule because I don’t know if I’m being stopped. If I will be deported for any reason. (…) we live like with a constant feeling of fear. I mean, we cannot completely get lost in the moment we’re always on guard.

RL: Yeah, this feeling is always present. Like, here I am definitely way more careful about servicing my car, keeping updated driver’s license and insurance cards, etc. I am terrified of the idea of being stopped with a broken light or an expired insurance card. Last summer, there were a number of peaceful protests around our town that I wanted to take part in, join the other students, but I just never felt safe enough to do so. There is always this feeling, this awareness that, no matter how integrated in the community you feel, this is just not your country. I asked Xavier about this, since he’s been here for 21 years.

[Xavier] Yes, absolutely. Even as faculty… Once you get like a position, like once I was hired… because I did a postdoc, and then once I was hired at Duke, like as an assistant professor, I was able to breathe a little bit, like ‘okay, I don’t need to worry about this until the next kind of’… because it was a visa for three years… And then you need to be renewed another three years. So even as faculty… It felt like there was always an end where there was a risk that things might go wrong. But… But that started to, yeah, to go away a little bit, because you feel the support of the institution. However… the feeling of not being an American, it’s, it’s always, it’s always there. Even… Yeah, it’s interesting, with a passport, and I got the passport, so I could vote. Like I got tired of paying taxes, and with the Trump administration I was very, very offended. I was like, I need to be able to vote. I’ve… Now I’ve written letters to this the senator, the North Carolina senator, and I feel like, ‘okay, they’re not going to kick me out of the country.’

[Dungeon of Fear, by John Bartmann playing on the background]

RL: Xavier touches on something I want to go back to: Donald Trump. We thought long and hard about whether to bring ‘politics’ to the podcast, but at the end of the day, this isn’t just ‘politics’. For international students, the Trump administration was an enormous source of stress and anxiety for four years, and we can’t talk about international students living in the US without talking about how four years of xenophobia impacted our lives. Many academic papers and news articles have been published on this exact subject and some have noted what they called a “Trump effect”: Following the 2016 presidential campaign, there was a drop in new international students coming to the US for the first time since this data collection began, a trend that continued through his presidency (e.g. Anderson and Svrluga 2018, Laws & Ammigan 2020). While researchers note there may be other reasons for the drop, it is not hard to imagine people prefer to live where they feel safe and welcome. International students go through so many hurdles, pay so many fees, to make sure we’re here legally, and we were always told that “as long as we’re legal”, we’d be safe. Well, it sure didn’t feel like it for the past four years.

[Junyao] Yes… Ah… yes. Those were hard times. I think at that period I checked the news every day ‘what they talked about’, ‘when do the new rules come out?’… You know you feel a little… unsafe. You feel… Sometimes you may be kicked out of the country. So, I think this unsafeness is really… make me feel not very good. You don’t know what will happened. And you don’t know what which rule will actually be carried out. I just want to finish my PhD!! Haha.

[song ends]

RL: Yeah, that was a rough summer. Also, I just want to acknowledge that for many of us, the international experience intersects with racial issues. I have been yelled at, to go back to my country, by a drunk white male whom I had never spoken to; Crisol tells me she’s been asked to show proof of legal status for something as simple as scheduling a doctor’s appointment, and most of us have had awful experiences at airports when entering the country. But it can be really hard to pinpoint what is “an international” experience per se, versus just plain old racism. Trump was very clear when he said he wanted more immigrants from countries like Norway, and less from “shithole countries”, but I have US born friends that are of Latino descent, and they share some of the same experiences.

This is a conversation for a whole other podcast, but the point is that your original country shapes your experience as a foreign student. That 2019 survey shows that students from Latin American and the Caribbean are the group that feel least welcomed in the US.

RL: But for all of us, regardless of where we’ve come from, the change in administration feels a bit like a target has been taken off our backs. We know there’s a lot of work to be done, but we can breathe again.

[Piano Sentiment 1, by Cory Gray playing in the background]

[Betta] It was a relief. I don’t know if I would have stayed if Trump would have had the win, at the end. Like. Now, I’m sure I can just… I can be fine. I can be like, I know that I will be good. I will probably as soon as the pandemic allows can be able to go back home and come back without too many problems without beside bureaucracy, but that was kind of scary is like it was like a little bit like and we’re not I don’t know if I want to stay in a place that doesn’t really welcome me.

[song ends]

RL: So, why do we do it? What makes over a million students leave their home countries every year and come to the US to pursue an education? Well, international students are not a monolith. Just like every other group of ‘humans’, there are a multitude of reasons why any one of us choose to come to the US. And unlike some might fear, a good portion of us does not want to stay. In fact, research has shown that few students arrive in the US with the intention of staying for good (Hazen and Alberts, 2006).

[Soft Inspiration, by Scott Holmes Music playing in the background]

Paula actually wanted to go to Australia for her studies originally, but decided to come to Duke because of the program features, and because it was closer to Colombia. Betta can’t wait to go back to Italy, and she came because of the amazing opportunity to work with Professor Cindy Van Dover in deep sea research. Phill also came to work with Cindy, plus the pay was better than what he was offered in the UK. He already had a job lined up in the UK after graduation, and he’s now back home with his wife.

The opportunity of being paid while studying what we love is something none of us takes for granted. Xavier, Paula, Crisol and I, we all reflected on the importance to keep the focus of our research in Latin America; we all believe that we are able to contribute much more to our home countries from here than we would if we had never left, and that is very important to us. Crisol is now back in Mexico, Paula also got a job in Mexico, and Xavier’s focus on Mexican fisheries directly and indirectly provides opportunities for many other students and researchers, both here in the US and back in Mexico, something he is certain would be much harder to provide if he had gone back. For Junyao, her journey actually started with her parents trying to push her “out of the nest” – they believed it was important for her to have a broader cultural and social view of the world, and she cherished her experience, so much so that she wanted to come here for graduate school. Her plans for after graduation? She wants to be a professor in Europe, so she can keep exploring different cultures. Regardless of why we came to the US or to Duke, what we all share is a deep appreciation of the academic environment and the wealth of opportunities we have as a result.

[Xavier] I looked around and there were no universities in Mexico that offered what I wanted to do – which was a mixed of anthropology and public policy. And the closest university actually that offered something relatively similar was the University of Arizona. So, the choice to go to the US was literally because there was nothing offered in Mexico, like that. But then being immersed in a group of people discussing papers, and thinking about issues, and at a large university where everybody’s kind of paid to think and… And I was in a… particularly in my PhD program and then postdoc, where there’s people from all over the world very interested in some of the same topics… That, that you know, for me that was like all the concept of a university. That’s awesome.

[song ends]

RL: Again and again, I watched my colleague’s eyes light up when they talked about the way science is done in the US, about Duke as an institution, and about the marine lab community.

[Betta] The university is insanely good. And the people that are in the in Beaufort are, like the community in Beaufort is very good too. But the university also, like it’s just the mix of it is, it’s very good. Like there are up and downs but I think the community in the Duke Marine Lab is always pretty much there.

RL: The marine lab community is, to me, one of the greatest paradoxes of living in a small town in rural North Carolina. As we drive through neighborhoods with Trump flags, we can’t help but wonder if some people wished we weren’t here. At the same time, we’ve found in this community an amazing support system, a reason to stay, a reason to love it here, a second family.

[Junyao] I think all the people here are so nice! This I really love here! We only have a small but very close community, and I also love my cohort! They are super great.

RL: For many of us, this is an experience of self-discovery, of breaking old paradigms,

[Xavier] I think it’s so great to be able to put your culture and your way of thinking in perspective, so it’s a privilege to be able to live in a different country where everything that you grew up with, hopefully, it’s up for questioning.

[Junyao] I found that spending 5 years here I found the biggest change of myself is I changed some opinions on some things. For example, I previously think that I need to do everything in the right time, in the right age, so I think ‘oh, I need to rush myself’ and do the right thing at the right time. But then I come here and I meet so many friends, so many people here, and they have so many unique life experiences, and I can see the possibilities in them. People should not be limited by what other people think. We do not need to follow other people’s lives. We need to choose what ourself wants. We need to follow our heart. We should do whatever we want. So that, I changed my mind. I see different living ways, so you can live in this way, and everyone respect, they do not judge you. You are different. So is that. I love it!

RL: Together, we learn each other’s cultures, improve language skills, and cook together. And I’m sure wherever we’ll go next, our friends in Beaufort and the foods we share will be added to the list of people and foods we miss the most. And obviously, living in such a tight knit community makes it very hard to leave it.

[Phill] I think it really comes from… it is a rural community, that it makes a very strong PhD community. So, you make the most of your surroundings, and you have lots of gatherings of people’s homes along the beach and stuff and… That, that very strong tight knit student group makes living there very easy. It makes leaving there quite difficult. It’s very different in the working world, not in the student bubble but… It’s great whilst it lasts.

[‘Oyster Waltz’ theme song playing in the background]

RL: I’ll make sure to enjoy it while it lasts for me. I welcome the renewed hope that a more progressive administration brings, while keeping in mind the enormous amount of work ahead of us.

RL: With that, I’d like to end with Xavier’s advice for international students living in the US, as it really resonated with me:

[Xavier] This is my advice: There’s a lot of… I think there’s a lot of feelings that if you go to the US, you must go back to your country. And there’s a lot of sense of guilt that builds from that. And I would like students to free themselves from that feeling, and just allow themselves to follow their curiosity, follow their intellectual curiosity to whatever it takes you, because it’s… you’re not going to be more satisfied by going to your country, if you’re not intellectually stimulated and motivated. It happened to me, and it’s so common with the Latin American students I interact with. So, I will say, don’t put that first. Put the intellectual curiosity and the stimulation first and everything will fall into place. Like, I feel I’ve been able to make many more contributions to Mexico, Mexico research, training students, then if I had said and done with my PhD, I’m going back to Mexico because I have a duty to fulfill.

RL: We hope you enjoyed this episode of PhDeep, a series where we explore the lives of PhD students. I want to thank everyone who contributed their time to talk to us; I had many more interesting topics and quotes than time allowed me to use. You can find out more about each of our interviewees on our website, sites.nicholas.duke.edu/seastheday/.

If you enjoy listening to us, please subscribe and write us a review, this will help other people find our podcast. You can also find us on Twitter and Instagram @SeasTheDayPod.

This podcast was written and produced by me, Rafa Lobo. Lisa Campbell co-wrote and edited the script.

Our theme song is by Joe Morton, our artwork is by Stephanie Hillsgrove.

Thanks for listening, see you next time!

[theme song fades away]

View References

Alberts, Heike and Hazen, Helen (2005). “There are always two voices…”: International Students’ intentions to stay in the United States or return to their home countries. International Migration, 43(3). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.2005.00328.x

Anderson, Nick and Svrluga, Susan (2018). What’s the Trump effect on international enrollment? Report finds new foreign students are dwindling. The Washington Post, November 13, 2018. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/report-finds-new-foreign-students-are-dwindling-renewing-questions-about-possible-trump-effect-on-enrollment/2018/11/12/7b1bac92-e68b-11e8-a939-9469f1166f9d_story.html

Baumgartner, Jason (2020). The economic value of international student enrollment to the U.S. economy. Association of International Educators (NAFSA), November 2020. Available at: https://www.nafsa.org/policy-and-advocacy/policy-resources/nafsa-international-student-economic-value-tool-v2

Castiello-Gutiérez, Santiago and Li, Xiaojie (2020). We are more than your paycheck: The dehumanization of international students in the United States. Journal of International Students 10(3). https://www.ojed.org/index.php/jis/article/view/2676

Dickler, Jessica (2020). Trump administration reverses course on foreign student ban. Consumer News and Business Channel (CNBC), July 14 2020. Available at: https://www.cnbc.com/2020/07/14/fight-heats-up-over-foreign-student-ban-as-more-than-200-schools-join-in.html

Duke University, (2020). Duke signs amicus brief supporting Harvard, MIT lawsuit against new visa directives. Duke Today, July 13, 2020. Available at: https://today.duke.edu/2020/07/duke-signs-amicus-brief-supporting-harvard-mit-lawsuit-against-new-visa-directives

Dwyer, Colin (2020). Harvard, MIT sue immigration officials over rule blocking some international students. National Public Radio (NPR), July 8, 2020. Available at: https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/07/08/888871130/harvard-mit-sue-immigration-officials-over-rule-blocking-some-international-stud

Glum, Julia (2017). Donald Trump may be scaring international students away from colleges in the U.S.. Newsweek, November 13, 2017. Available at: https://www.newsweek.com/trump-international-education-study-abroad-708667

Hacker, N.L and Bellmore, E.N. (2020). “The Trump effect”: How does it impact international student enrollment in U.S. colleges? Journal of Critical Thought and Praxis 10(1), Article 8. https://doi.org/10.31274/jctp.11588

Hazen, Helen and Alberts, Heike (2006). Visitors or immigrants? International students in the United States. Population, Space and Place 12, pp 201-216. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.409

Jordan, Miriam and Hartocollis, Anemona (2020). U.S. rescinds plan to strip visas from international students in online classes. The New York Times, July 16, 2020. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/14/us/coronavirus-international-foreign-student-visas.html

Jordan, Kanno-Youngs and Levin (2020). Trump visa rules seen as way to pressure colleges on reopening. The New York Times, July 7, 2020. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/07/us/student-visas-coronavirus.html

Kuo, Ya-Hui (2011). Language challenges faced by international graduate students in the United States. Journal of International Students, 1(2). https://ssrn.com/abstract=1958387

Laws, Kaitlyn and Ammigan, Ravichandran (2020). International students in the Trump era: A narrative view. Journal of International Students, 10(3). https://www.ojed.org/index.php/jis/article/view/2001

Lee, Jenny (2020). international students shouldn’t be political pawns. Inside Higher Ed, July 8, 2020. Available at: https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2020/07/08/government-regulation-about-international-students-strong-arming-colleges-resume

Saul, Stephanie (2018). As flow of foreign students wanes, U.S. universities feel the sting. The New York Times, January 2, 2018. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/02/us/international-enrollment-drop.html

Skinner, M., Luo, N., and Mackie, C. (2019). Are U.S. HEIs meeting the needs of international students? New York: World Education Services. Available at: https://www.wes.org/partners/research/

Specia, Megan and Abi-Habib, Maria (2020). ‘Maybe I shouldn’t have come’: U.S. visa changes leave students in limbo. The New York Times, July 9, 2020. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/09/world/international-students-visa-reaction.html

Treisman, Rachel (2020). ICE: Foreign students must leave the U.S. if their colleges go online-only this fall. National Public Radio (NPR), July 6, 2020. https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/07/06/888026874/ice-foreign-students-must-leave-the-u-s-if-their-colleges-go-online-only-this-fa

US District Court of the District of Massachusetts, 2020. Complaint for declaratory and injunctive relief. Case 1:20-cv-11283. Filed 07/08/20. Available at: https://www.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/content/sevp_filing.pdf

Yao, Christina and Viggiano, Tiffany (2019). Interest convergence and the commodification of international students and scholars in the United States. Journal Committed to Social Change on Race and Ethnicity, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.15763/issn.2642-2387.2019.5.1.81-109

*All newsclips audio played in the intro were downloaded from news sources that published them under the Creative Commons license. The short clips came from CNBC, PBS, MSNBC and Al Jazeera.

The following songs were used in the sound mixing:

CC-BY-NC: Lagoon by Drama for Yamaha

CC-BY-NC: Happy Boccherini by Lanark

CC-BY-NC-SA: Morning Movement by Kathleen Martin

CC-BY-NC: Beat Poets, by Snake Oil Salesman

CC-BY-NC: Children’s Joy, by Borrtex

CC0: Bouncy Gypsy Beats, by John Bartmann

CC-BY-NC: Safari Time, by Joh Bartmann

CC-BY-NC: Happy Boccherini, by Lanark

CC-BY-SA: Dungeon of fear, by John Bartmann

CC-BY-NC: Piano Sentiment 1, by Cory Gray

CC-BY-NC: Soft Inspiration, by Scott Holmes Music

They were all downloaded under Creative Commons licenses from the freemusicarchive.org. We thank artists, curators and website hosts for making free songs available. This episode would not have been the same without them.