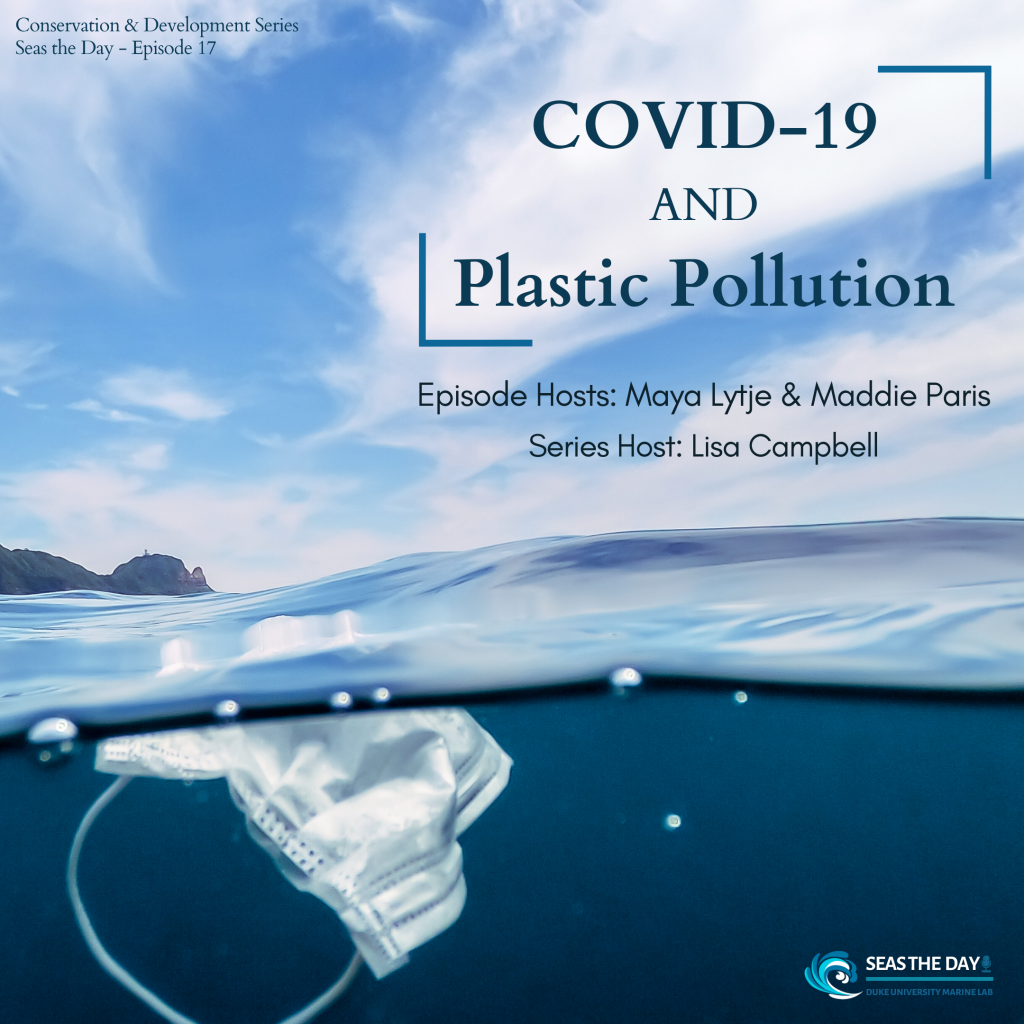

In this podcast, Maddie Paris and Maya Lytje discuss how COVID-19 has influenced marine plastic pollution. They explore the marine conservation, human health, and international equity implications of plastic pollution through the lens of the ongoing pandemic. In exploring these issues, the pair interviews Dr. Dan Rittschof, a professor at the Duke Marine Lab, and John Hocevar, the Greenpeace USA Oceans Campaign Director, to get their perspectives.

Listen Now

Episode Hosts

Maya Lytje is a sophomore at Duke University from Melrose, MA. She is majoring in Public Policy and pursuing a certificate in Human Rights. Maya is passionate about environmental justice and policy.

Maddie Paris is a junior at Duke University, where she is double majoring in Biology and Environmental Sciences. A native Floridian, Maddie is passionate about marine ecology and conservation. She is particularly interested in the implementation and assessment of marine conservation interventions.

Interviewees

John Hocevar is the Oceans Campaign Director at Greenpeace USA. An accomplished campaigner, explorer, and marine biologist, John has helped win several major victories for marine conservation since becoming the director of Greenpeace’s oceans campaign in 2004.

Series Host

Dr. Lisa Campbell hosts the Conservation and Development series. The series showcases the work of students who produce podcasts as part of their term projects. Lisa introduced a podcast assignment after 16 years of teaching, in an effort to direct student energy and effort to a project that would enjoy a wider audience.

Learn more about plastic pollution

Maddie and Maya suggest these documentaries!

Supplemental material for this episode

Transcript: COVID-19 and Plastic Pollution Podcast Script

[Music – The Oyster Waltz]

Lisa Campbell: Welcome to Seas the Day, a podcast from the Duke University Marine Lab. I’m Lisa Campbell, and today we have an episode from our Conservation and Development series. In it, Maya Lyjtle and Maddie Paris discuss how the COVID-19 pandemic contributes to marine plastic pollution. As it has with many pre-existing social problems, COVID-19 has both exacerbated existing challenges associated with marine plastic pollution and introduced new ones. So, the story of marine plastic pollution has changed quite a bit since we brought you our first episode on this issue, just over 7 months ago. For regular listeners, you may remember Cass Nieman and Ali Boden talked about the Plastic Burden in episode 3 of Seas the Day. Listening to both episodes, it’s striking how the challenges are eerily similar and also distinct. So if you missed episode 3, go back and have a listen. But now, over to Maya and Maddie, with episode 17: COVID-19 and plastic pollution.

[News audio clips on COVID-19 and environmental impacts, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=78EvLw2hs2U (from 15-30 seconds)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UVxWWW63SdU]

Maddie: As the Covid-19 pandemic hit the world in 2020 it disturbed many complex global processes, in ways we are still trying to understand. At the very beginning, we heard surprising reports of wild animals taking back urban areas, dolphins swimming in Venice for the first time in decades, and a decrease in CO2 emissions due to lockdowns and travel restrictions. Such reports made us wonder, could one of the many unintended consequences of the Coronavirus pandemic actually be improved environmental health? Interesting question.

Maddie: Hi, I’m Maddie.

Maya: And I’m Maya. And we’re Duke undergraduates studying at the Duke Marine Lab. We’re here to introduce the complexities surrounding COVID-19 and plastic pollution. When taken from this perspective, the pandemic’s impacts on the environment were much more complicated than those original reports seem to suggest.

[New audio clips, from

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=35ZMqizPfoo (first 15 seconds)

https://www.cbsnews.com/video/environmentalists-fear-increase-in-plastic-pollution-amid-coronavirus-pandemic/#x (first 20 seconds)]

Maya: The COVID-19 pandemic has altered many aspects of our way of life. Personal protective equipment (or PPE) became incredibly necessary to protect frontline workers and prevent the spread of COVID-19. However, there have been many external consequences from the production and disposal of PPE and other covid-related plastics.

Maddie: We by no means want to minimize the extensive loss of life and the toll this has had on everyone. PPE and safety guidelines should rightfully be prioritized in respect to the pandemic. The scope of this podcast is limited to the effects of pandemic on plastic pollution but we do recognize the immense hardships that Covid has brought on and the necessity for all of the safety measures that have been put in place.

Maya: In this podcast, we will examine the many environmental and human impacts of the synergy of covid and plastic pollution. We will begin by giving a brief overview of the problem of plastic pollution and then we’ll get into how covid has influenced plastic production, use, and disposal. Next we’ll talk about how this has affected both marine life and human health. Then we’ll take a broader look at how covid plastic pollution interacts with inequalities on an international scale. Finally, we’ll dive into some possible solutions.

Maddie: So let’s get started.

Maya: Plastic pollution was already an issue before the covid pandemic. According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, about 8.3 billion tonnes of plastic has been produced since the 1950s, which is the weight of a billion elephants or 47 million blue whales.

Maddie: Wow, I can’t even imagine!

Maya: I know! Of this 8.3 billion tonnes, only about 9% of plastic has been recycled, 12% has been burned and the remaining 79% has ended up in landfills or in the environment, according to researchers from UC Santa Barbara. If the present rate of pollution continues, the World Economic Forum reports, by 2050 there will be more plastic than fish in the ocean.

Maddie: Huh, that’s a powerful image, more plastic than fish. But at least before the pandemic, there was some momentum building up to combat plastic pollution. Countries, states, cities, and businesses were introducing plastic bag bans, cutting down on straws, and reducing other single-use items.

Maya: And then the pandemic hit.

Maddie: We spoke with John Hocevar at Greenpeace USA to get his perspective.

John Hocevar: My name is John Hocevar and I’m the Oceans Campaign Director for Greenpeace USA.

You can’t go anywhere without seeing discarded plastic PPE on the ground. And anything that ends up on the ground is going to end up in waterways. So that’s been a huge issue. Over 200 billion pieces of single use PPE is discarded or used every month, and none of that is recyclable. So pretty shocking how quickly we created a new problem. But you know there are a bunch of good things that came of this too. All the plastic that we interact with in fast food restaurants for example. People visited fast food places a lot less than they did before the pandemic. So that’s a lot of plastic that we didn’t end up using. People cooked at home a lot more, so that’s more reuse and less packaging. Then on the other hand, we did a lot more takeout, we did a lot of ordering food for delivery and so that adds a whole bunch more of plastic containers and plastic utensils and plastic crap than we’re used to.

Maya: To better understand these shifts in plastic waste due to Covid, let’s travel to Jakarta Bay in Indonesia, where plastic covers the water as far as the eye can see. Thirteen rivers flow into Jakarta Bay carrying plastic bottles, styrofoam, processed wood, plastic wrap, clothing, masks, gloves, and more along with them. The livelihoods of the coastal communities living in and around Jakarta Bay are directly reliant on these ecosystems and are therefore greatly impacted by the amount of plastic waste.

Maddie: Plastic pollution is not a new problem in Jakarta Bay, but researchers from the Indonesian Institute of Science have recently studied this area through the lens of covid plastic pollution. They found that PPE consisted of 16% of the waste coming into the Bay. Prior to the pandemic PPE was less than 1% of the total plastic pollution. Comparing April 2019 to April 2020, plastic wrapping, PPE, and plastic waste as a whole increased significantly in Jakarta Bay.

Maya: These statistics are also only from April 2020, so one could imagine the impact is even greater now that the pandemic has continued for an entire year. Even in uninhabited areas like the Soko Islands in Hong Kong, 70 discarded face masks were found on just a 100-meter stretch of beach in February 2020 according to OceansAsia, a Hong Kong-based marine conservation organization.

Maddie: These trends were seen worldwide. The Ocean Plastic Leadership Network reports a 30% increase in plastic pollution during the pandemic and another research group found that illegal plastic waste disposal has risen by 280% globally during Covid-19. According to OceansAsia, an estimated 1.56 billion face masks entered the oceans in 2020.

Maya: Another consequence of the pandemic highlights the complexity of these interactions: it actually became cheaper to manufacture plastics during the pandemic! We saw the oil market collapse as countries went into lockdown and transportation decreased globally. Oil prices dropped by 71% from January to April 2020, and because the production of plastic relies heavily on oil, it became much cheaper to produce these goods, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Maddie: All of these factors led to a rise in plastic pollution during the covid pandemic.

Maya: So why should we care? What are the impacts?

Maddie: John Hocevar from Greenpeace explains how plastics enter the environment.

John: Outside my house right now, there’s a bunch of plastic garbage on the sidewalk and on the side of the road and it’s pouring so some of that is washing down the drain on the corner just right there and it goes into the Anacostia River and then out into the Potomac and the Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic Ocean. And that’s kind of the fate of a lot of the single use plastic that we produce and use.

Maddie: Clearly, marine life is impacted by the increase in plastic pollution. One in three sea turtles, nine out of ten seabirds, and half of all dolphins and whales have ingested plastic at some point in their lives, according to various studies.

Maya: In April 2020, Dutch volunteers were participating in a canal cleanup, picking up marine debris which was mainly composed of PPE. One volunteer reached out to pick up a discarded medical glove. As she picked it up, she noticed something odd about the used glove. A small tail was peaking out of the end, and inside, trapped, they found a dead fish. This was the first recorded incidence of a PPE-related entanglement fatality, but it’s probable that this has become much more common than we realize.

Maddie: In addition to entanglement, there have also been reports of marine animals eating PPE and using single-use covid-19 masks as nesting materials, according to a study by the Naturalis Biodiversity Center in the Netherlands. PPE and other covid related plastics can cause serious health effects for marine organisms.

Maya: According to that same Dutch study, ingesting plastics can block the gastrointestinal tracts of organisms or trick them into thinking they don’t need to eat, leading to starvation. Many toxic chemicals can also adhere to the surface of plastic and, if ingested, contaminated microplastics could expose organisms to high concentrations of toxins.

Maddie: According to a Peruvian study, PPE is also often based on low-density polymers, which may serve as vectors for invasive species and microbial pathogens. PPE could also serve as a vector and source of chemical contaminants. Organic compounds and heavy metals interact with plastic surfaces and can be absorbed by the plastic. Weathering conditions cause plastics to leach toxic additives like flame retardants and Polychlorinated biphenyls (or PCBs).

Maya: All of these marine health risks associated with COVID-19 plastic add stressors to the environment, impede healthy ecosystem function, and reduce population sizes. It is much more difficult to conserve marine ecosystems when the organisms are under constant stress from pollution.

Maddie: Ok, so we know that plastic pollution has greatly increased during the covid pandemic and that it negatively impacts marine life, but what does this mean for humans?

Maya: We spoke to Dr. Dan Rittschof, a professor at the Duke Marine Lab.

Dr. Dan Rittschof: I’m Dan Rittschof. I’m the Norman Christensen Distinguished Professor of the Environment.

Maya: He explained some of the human health impacts of plastic pollution.

Dr. Dan: So plastics are really kind of dirty things, chemically. And those chemicals leach out and they contain a lot of different kinds of things like endocrine disruptors, heavy metals, flame retardants, plasticizers, that impact biology. The plasticizer, Dibutyl Phthalate, causes brain disruption in human children. It’s an endocrine disruptor. Women who have high levels of plasticizer in their blood have boy children, when the fetus, when the child is actually born, that have tiny testicles.

Maya: These challenges are compounded by environmental injustices at the community level. Low-income communities face more health impacts near plastic production sites, have greater exposure to toxins and waste, and bear the brunt of the impacts of improper plastic disposal and incineration.

Maddie: John Hocevar had a lot to say about this.

John: For the communities that are closest to where natural gas is extracted, especially through fracking for plastic, there are pretty serious implications: contamination of water supply. And then where plastic is actually manufactured, these refineries are very dangerous for the communities around them, often especially communities of color. There’s a strong environmental justice aspect to the production of plastic.

Maddie: Covid plastic pollution impacts both human health and exacerbates domestic inequalities. Now zooming out, let’s look at how this plays out on an international scale between the Global North and South. In this section, we will be using Global North to mean wealthier and more industrialized countries mainly concentrated in the North and Global South to mean lower-income countries mainly occurring in the South.

Maya: Covid’s impacts on plastic production and disposal have exacerbated and made more visible related global inequities. Countries in the Global North currently use more advanced technologies to control the emissions of toxic byproducts, but lower income countries still rely on older incineration technologies that emit toxic chemicals that can have serious human health implications. Poor air quality and persistent toxic chemicals can exacerbate disease patterns in these developing countries, according to the UN Environment Program.

Maddie: Furthermore, countries in the Global North export waste to the Global South, outsourcing the disposal of plastic waste and forcing countries in the Global South to deal with the implications of such waste. According to the International Solid Waste Association, people living along rivers and coastlines in China, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam are the most impacted by plastic pollution. Think back to Jakarta Bay and the rivers of plastic that people live around. There is a great disparity here in the consumption of plastics and those bearing the burdens of such use.

Maya: Exportation of plastic waste to countries in the Global South continued unabated during the pandemic. In 2020, The United States Commerce Department showed that the US continued to export about 28,000 metric tons per month of its plastic waste to countries in the Global South. However, in the Philippines, Vietnam, and India, where much of this plastic waste is going, as much as 80% of the recycling industry was not operating during the height of the pandemic, according to the Basel Action Network.

Maddie: This is often how plastic waste ends up in our oceans, as it is not fully contained or managed. Inequities in the international sphere as to who consumes and who bears the brunt of the consumption is intimately tied to development status.

Maya: The average person living in North America and Western Europe consumes 220 lbs of plastic per year whereas the average person in Asia consumes ⅕ that level.

Maddie: If you google it, the top five plastic polluters are China, Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam, and Thailand. But considering what we just discussed, a lot of this waste isn’t actually theirs, it really originates in the Global North.

Maya: It’s unfair that these countries are blamed and labeled as big plastic polluters when it’s actually countries in the Global North that are consuming so much plastic and then exporting it to other countries for them to deal with.

Maddie: As waste is imported into countries in the Global South, human health declines, environmental quality declines, and it becomes even harder for these countries to make strides in development.

Maya: The burden of imported plastic waste was heightened because countries in the Global South also had less resources and were less prepared for the COVID pandemic.

Maddie: Clearly the covid plastic pollution problem is really complex and ties to many global inequalities. This problem spans issues relating to development, human health, and ecosystem wellbeing.

Maya: So are there any solutions to these wicked problems?

Maddie: Well, the solutions to plastic pollution are complex, transboundary, and multilateral. Most solutions aren’t specific to covid since plastic pollution reaches beyond the pandemic. However, the pandemic does enhance the need for solutions due to the increase and long term nature of covid-related plastic.

Maya: There is currently a very limited international policy framework to address marine plastic pollution. Only in recent years has public momentum encouraged governments and the United Nations to begin to prioritize plastic pollution as a threat to marine life. For example, the UN Basel Convention is attempting to directly remedy the international plastic pollution crisis. New rules to the Convention related to plastic exportation came into effect on January 1st, 2021.

Maddie: I actually was able to attend a United States Senate hearing on U.S. government efforts to address ocean plastic pollution while I worked at Greenpeace USA, and I learned a lot about the Basel Convention there.

Maya: Oh that sounds like such a cool opportunity! What was it like?

Maddie: Due to the pandemic, I attended over Zoom, but I was still able to learn a lot about the Senate’s views on international plastic pollution.

Maya: It’s encouraging to hear that there were still ongoing discussions on international plastic pollution in the midst of the pandemic. What were your biggest takeaways?

Maddie: There was support for Pro Blue, which is a multi-donor trust fund housed at the World Bank that supports the development of integrated, sustainable, and healthy marine and coastal resources. There was concern from the State Department that Pro Blue focuses on limitations on production and could undermine the growing recycling market. While the US isn’t a signatory to the Basel Convention, at this hearing senators professed support for curbing international plastic pollution and made plans to allocate more funding to the US Agency for International Development for waste management programs in countries in the Global South.

Maya: Oh yeah, a lot of organizations think that improving funding and capacity for waste management could be the best step to curbing plastic pollution. There are some non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that focus solely on getting more funding for waste management infrastructure in Global South countries. One NGO called “WasteAid”, from the UK, is working to do just that. Their mission is to improve waste management and infrastructure in low-income nations. If more government aid and organizations contributed to this goal, it could help improve waste conditions in the global south, mitigate the effects of plastic pollution, and contribute to a healthier world population.

Maddie: We asked Dr. Rittschof what he thinks some possible solutions are to the problem of plastic pollution.

Dr. Dan: There needs to be policies put in place that require plastics to be reengineered so they’re not tasty and so they don’t last forever.

Maya: We also asked John Hocevar what Greenpeace is doing to solve the global plastic pollution crisis.

John: I think above all we need to move away from single use plastic and towards reuse. That’s kind of fundamental. We need to make and use less plastic. That said, in the meantime, we can definitely design the plastic that we are using a little bit better, so it’s more likely to be recycled. The more that we can standardize materials and design the easier it will be to make sure that things are recycled, and even better, reused. We do need to invest in shoring up our recycling system. One of the things that will help a lot is nationalizing our bottle deposit program. We have seen everywhere that these programs are in place: it’s basically if there’s a 5 or 10 cent deposit on a bottle it dramatically increases the amount of bottles that are recovered instead of lost. So nationalizing that will also be an important part of the overall solution.

Maddie: But what about covid-specific pollution?

Maya: For one, Duke University has been working on reducing medical waste by creating a process for the safe reuse of medical masks. Using hydrogen peroxide vapor as a decontaminant, Duke was able to reuse N-95 masks up to 10 times. This strategy could be expanded to other medical waste materials that contribute to plastic pollution even after the pandemic.

Maddie: Wow, that’s so cool to have this research happening in our own backyard at Duke.

Maya: And since we’ll probably still be wearing masks for a while, another covid-specific suggestion from the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals is to snip the straps on face masks before discarding them to help prevent animals from getting entangled in them.

Maddie: But of course there is no one solution.

John: You know it can seem a little overwhelming when you think about how much plastic there is almost everywhere you look. You can want to do the right thing, and really work hard to avoid or minimize plastic in your life and the options are not always that easy to find. So this isn’t about beating yourself up or feeling guilty. We should all do what we can to limit the amount of plastic that we bring into our lives, but our real power and the big solutions are when we work together to make sure corporations and governments understand that we want better choices,that our healthy for our communities and for the planet.

Maddie: Before the pandemic, the world was shifting to reusability and there was widespread concern about plastic pollution. Due to the pandemic, health and safety rightfully took priority. Public awareness and international motivation was rising to address the issue of global plastic pollution until covid interrupted this momentum.

Maya: After the pandemic, we need to shift the narrative back to reusability and not be complacent in our use of single-use plastics. Covid did more than just increase pollution; it made global inequity much more visible and we can do so much better than going back to normal. While covid is still raging on and PPE is very much necessary, we must make sure to move forward with innovative solutions and focus on reducing plastic pollution.

Maddie: Think back to the fish found trapped in the medical glove and the people living along Jakarta Bay, surrounded by plastic waste from other countries. Is this the world we want to live in? Governments, companies, and everyday people need to do better to create a more equitable and healthy future.

Maya: So we started off with the question: has the pandemic been positive or negative for the environment? Obviously through the lens of covid and plastic pollution, we’d argue that it has exacerbated previous issues relating to marine conservation and human development.

Maddie: Maybe a better question would be: what can learn from this moment to move forward?

[Music]

Maya: We’d like to thank our interviewees, Dr. Dan Rittschof and John Hocevar, for their contributions in the production of this podcast. If you’d like to learn more, we encourage you to check out these two documentaries: A Plastic Ocean and The Story of Plastic. Thanks so much for listening.

[Music]

You’ve been listening to Seas the Day. We hope you enjoyed today’s episode, and if you want to find our earlier episode on plastic pollution, episode 3, you can find it and all of our past episodes on our website, www.sites.nicholas.duke.edu/seastheday

Today’s episode was written and produced by Maya Lyjtle and Maddie Paris.

Final editing was done by Rafa Lobo.

Our theme music was written and recorded by Joe Morton.

Our artwork is by Stephanie Hillsgrove.

Follow us on Instagram and Twitter @seasthepod. And if you enjoyed this episode, please leave us a rating in Apple podcasts.

References:

(2020, November 19). Global Plastic Recycling Industry. GlobeNewswire News Room. https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2020/11/19/2130106/0/en/Global-Plastic-Recycling-Industry.html#:~:text=Illegal%20plastic%20waste%20disposal%20has,or%20even%20reverse%20the%20process.

Avery, S. (2020, March 26). Duke Starts Novel Decontamination of N95 Masks to Help Relieve Shortages. Duke School of Medicine. https://medschool.duke.edu/about-us/news-and-communications/med-school-blog/duke-starts-novel-decontamination-n95-masks-help-relieve-shortages.

Baulch, S., & Perry, C. (2014, February 11). Evaluating the impacts of marine debris on cetaceans. Marine Pollution Bulletin. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0025326X13007984.

Brock, J. (2020, October). Special Report: Plastic pandemic: COVID-19 trashed the recycling dreamB. Yahoo! Finance. https://finance.yahoo.com/news/special-report-plastic-pandemic-covid-111315407.html?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZWNvc2lhLm9yZy8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAAAQUh5gHmiIzJ6oJlXogb15-nXCVxXCWSxZnhyP6wfOKK8BX0uLD7aLnQbHOnwQk_rN6_XsSo1Sl4_pQsnHtBcZLkXmVDkHFbvqAW3KcN_s28zejj1w_A7o9-852X_AArAXfVMF7WEzv4UihAc-CyNp1J0Jl3ImDttLDPpWCSsgg.

Camp, K., Mead, D., Reed, S., Sitter, C., & Wasilewski, D. (2020, October 1). From the barrel to the pump: the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on prices for petroleum products : Monthly Labor Review. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2020/article/from-the-barrel-to-the-pump.htm.

Canning-Clode, J., Sepúlveda, P., Almeida, S., & Monteiro, J. (2020, July 30). Will COVID-19 Containment and Treatment Measures Drive Shifts in Marine Litter Pollution? Frontiers. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2020.00691.

CBS Interactive. (2020). Environmentalists fear increase in plastic pollution amid coronavirus pandemic. CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/video/environmentalists-fear-increase-in-plastic-pollution-amid-coronavirus-pandemic/#x.

Cole, R. (2017, July 24). 8.3 billion tonnes of plastic produced since 1950, say researchers. Resource Magazine. https://resource.co/article/83-billion-tonnes-plastic-produced-1950-say-researchers-11997.

Cordova, M. R., Nurhati, I. S., Riani, E., & Nurhasanah, M. Y. (2020, December 18). Unprecedented plastic-made personal protective equipment (PPE) debris in river outlets into Jakarta Bay during COVID-19 pandemic. Chemosphere. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S004565352033558X?via%3Dihub.

De-la-Torre, G. E., & Aragaw, T. A. (2020, November 28). What we need to know about PPE associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in the marine environment. Marine Pollution Bulletin. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0025326X20309978?via%3Dihub.

Dengate, C. (2016, July 15). Turtle Plastic Study: Sometimes You Don’t Want To Be Proven Right. HuffPost Australia. https://www.huffingtonpost.com.au/2016/03/17/turtles-marine-plastic_n_9455496.html.

DW News. (2020). Coronavirus: Good for the environment? | Covid-19 Special. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UVxWWW63SdU.

Ford, D. (2020, August 17). COVID-19 Has Worsened the Ocean Plastic Pollution Problem. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/covid-19-has-worsened-the-ocean-plastic-pollution-problem/.

Garcés, M. (2018). Op-Ed: At last the tide is turning on plastic | General Assembly of the United Nations. United Nations. https://www.un.org/pga/73/2018/12/18/op-ed-at-last-the-tide-is-turning-on-plastic/.

General Assembly of the United Nations. (2019). Plastics . United Nations. https://www.un.org/pga/73/plastics/.

Geyer, R., Jambeck, J. R., & Law, K. L. (2017, July 1). Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Science Advances. https://advances.sciencemag.org/content/3/7/e1700782.full.

Hiemstra, A.-F., Rambonnet, L., Gravendeel, B., & Schilthuizen, M. (2021, March 22). The effects of COVID-19 litter on animal life. Brill. https://brill.com/view/journals/ab/aop/article-10.1163-15707563-bja10052/article-10.1163-15707563-bja10052.xml.

ISWA. (2021, April). Introducing CLOCC to ISWA’s Network. ISWA. https://www.iswa.org/blog/introducing-clocc-to-iswas-network/.

Kaplan, R., & Stuchtey, M. (2020). Collateral damage: COVID-19’s impact on ocean plastic pollution. Greenbiz. https://www.greenbiz.com/article/collateral-damage-covid-19s-impact-ocean-plastic-pollution.

Lusher, A., Hollman, P., & Mendoza-Hill, J. (2017). Microplastics in fisheries and aquaculture: Status of knowledge on their occurrence and implications for aquatic organisms and food safety. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. http://www.fao.org/3/i7677e/i7677e.pdf.

Mathuros, F. (2016). More Plastic than Fish in the Ocean by 2050: Report Offers Blueprint for Change. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/press/2016/01/more-plastic-than-fish-in-the-ocean-by-2050-report-offers-blueprint-for-change/.

McSweeney, E. (2021, March 30). Covid-19 PPE litter is killing wildlife. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2021/03/30/world/covid-waste-wildlife-scli-intl-scn/index.html.

NBC News Now. (2020). Cleanup Crews Say Masks And Gloves Are Polluting The Ocean. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=35ZMqizPfoo.

NewsOnABC. (2020). Coronavirus: Fewer people, more animals on streets | The World. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=78EvLw2hs2U.

OceansAsia. (2020, December 7). Estimated 1.56 billion face masks will have entered oceans in 2020 – OceansAsia Report. OCEANS ASIA. https://oceansasia.org/covid-19-facemasks/.

Pickett, J. (2021, February 4). US Continues to Export Plastic Waste to Developing Countries as 2021 International Trade Ban Looms. Basel Action Network. https://www.ban.org/news/2020/11/11/us-continues-to-export-plastic-waste-to-developing-countries-as-2021-international-trade-ban-looms.

Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. (2020). ‘Snip the straps’ off face masks as Great British September Clean launches. RSPCA. https://www.rspca.org.uk/-/news-face-masks-spring-clean.

Stokes, G. (2020, March 3). No Shortage Of Masks At The Beach. OCEANS ASIA. https://oceansasia.org/beach-mask-coronavirus/.

Wilcox, C., Van Sebille, E., & Hardesty, B. D. (2015). Threat of plastic pollution to seabirds is global, pervasive, and increasing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. https://www.pnas.org/content/pnas/112/38/11899.full.pdf.