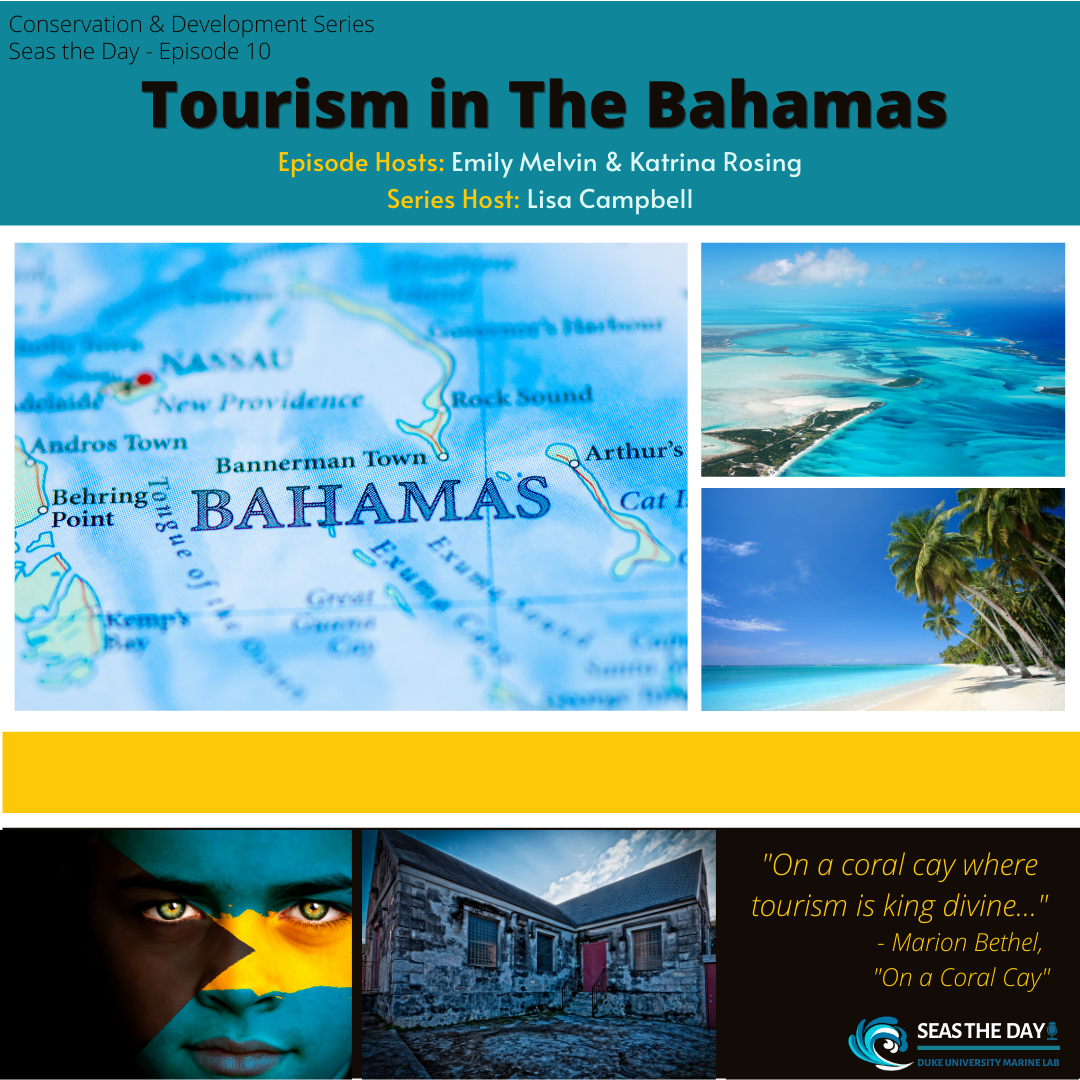

In this episode, Emily Melvin and Katrina Rosing delve into the complexities of tourism in the Bahamas. The two discuss how tourism affects Bahamian identity and reflects colonial legacies even today. In exploring these issues, they interview Tarran Simms of the Bahamas Ministry of Tourism’s sustainability department. Tarran discusses his views of Bahamian identity, the interplay of that identity with tourism, and the emergence of new forms of tourism in the Bahamas.

Listen Now

Episode Hosts

Emily Melvin, Masters of Environmental Management, 2020

Emily completed her Masters at Duke’s Nicholas School of the environment, in the Coastal Environmental Management program. Since 2018, Emily has been working with a dive resort in the Bahamas, Small Hope Bay Lodge, along with several others (including Tarran Simms who features in this episode) to start a new non-profit organization, the Small Hope Bay Foundation, with a mission to create capacity for environmental and economic sustainability on Andros Island, Bahamas. Emily spent the summer of 2019 on Andros working on strategic planning for the Foundation and conducting research for her Master’s Project, “Tourism, Environmental Stewardship, and Community Engagement on Andros Island, Bahamas,” under the guidance of advisor Lisa Campbell. Emily is now pursuing her PhD in Coastal Sciences at the University of Southern Mississippi, and she hopes to continue working in the Bahamas for her dissertation research, examining the role of international power and politics in Hurricane Dorian recovery.

Katrina Rosing, Wittenberg University

Katrina is a senior at Wittenberg University studying biology and marine science. She spent the spring of her junior year at the Duke Marine Lab. After graduation, Katrina plans to attend graduate school to study coral conservation.

Interviewees

Tarran Simms is a Coordinator in the Sustainable Tourism Unit at The Bahamas Ministry of Tourism. Tarran has a Bachelor of Science in Small Island Sustainability with a focus in Eco-tourism and Development from the College of the Bahamas, and a Master of Science in Tourism Hospitality Management / Master of Arts in Research on Islands and Small States from the University of Malta. Mr. Simms has received national recognition in the Bahamas. He received the 2016 Youth in the Environment award and was selected as a youth delegate to climate change negotiations. In his free time, he enjoys SCUBA diving and fishing.

Ariel Seymore reads Marion Bethel’s poem, “On a Coral Cay.” Marion Bethel is a Bahamian attorney, writer, and activist. She received a Bachelor and Masters of Arts in Law from Cambridge University, and has been practicing law in the Bahamas since 1986. Marion’s work has been featured at poetry festivals in the Caribbean and the Americas. You can read more of her poems in the 2009 collection Bougainvillea Ringplay. Source: https://peaceisloud.org/speaker/marion-bethel/

Series Host

Dr. Lisa Campbell hosts the Conservation and Development series. The series showcases the work of students who produce podcasts as part of their term projects. Lisa introduced a podcast assignment after 16 years of teaching, in an effort to direct student energy and effort to a project that would enjoy a wider audience.

Supplemental material for this episode

Transcript: Tourism in The Bahamas

Musical interlude

Lisa Campbell: Hey there listeners, welcome back to Seas the Day. I’m your host Lisa Campbell, and today we return to our conservation and development series. We airing this episode in January 2021, and the pandemic rages on. Although vaccines give us hope, unfettered movement, travel, and tourism are still some way off in the future. With that in mind, we thought it might be a good time – good time? – to share several episodes on tourism. Tourism is a classic conservation and development conundrum. It is one the world’s largest industries: before the pandemic, for the year 2019, the World Tourism Organization reported 1.5 Billion international tourist arrivals, and 9 billion domestic tourism trips. That’s 10.5 billion tourists. 10.5 billion. An industry of this size has significant economic, social, and environmental impacts, both positive and negative. We have three episodes that explore these impacts, and some of the ways people, governments, non-government organizations, and businesses have tried to increase the positive benefits and decrease the negative.

In today’s episode, Emily Melvin and Trina Rosing were inspired by their own experiences as tourists to the Bahamas. They use the podcast to contextualize those experiences in the history of tourism to the islands and in contemporary efforts to increase local retention of benefits from tourism development. Enjoy!

Sounds of waves on beach

Ariel Seymore [reading poem by Marion Bethal]: “On a coral cay / where tourism is king divine / and banking a silver prince / where sugar never was, no hardly / where cotton never was, not much / to the smooth-skinned hand / the whale done dead / to the hardened hand / the whale line done break / We are out to sea / we are out to sea

We no longer whale or wreck / privateer pirate or run rum / as the economic ties change / We do not grieve our loss / of the cassava Bahamians / to the Sargasso sea / for we are the conch Bahamians / we do not pain / for we do not know / we have lost

On a coral cay / where we live / on a tourist plantation / and a banking estate / where the air is conditioned / and so are hands that do not know / the fishing line or pineapple soil / we produce nothing, or hardly / and we service the world, or nearly / in our conditioned service / we are blessed waiters / of grace divine.”

Emily Melvin: Hi, I’m Emily Melvin and I’m a Master’s student at the Duke Marine Lab.

Katrina Rosing: And I’m Katrina Rosing a Whittenburg undergraduate studying at the Duke Marine Lab. We just listened to a poem called “On a Coral Cay” written by Marion Bethel, a Bahamian writer and attorney. We came across this poem in a paper by Angelique Nixon, a professor at the University of the West Indies who was born and raised in Nassau. According to Nixon, the poem shows how plantation slavery has led to the success of the tourism and banking industry in the Bahamas, leaving few Bahamians to work in industries such as fishing and agriculture. Nixon says that because of these remnants of slavery, Bahamian people are quote “conditioned to provide service for both the tourist and banking industries.”

Emily: And this poem really got us thinking about our own experiences in the Bahamas, and how when we visit as tourists we may not really get the full picture of what the tourism industry means to Bahamians and the history behind all of that.

Katrina: So today we’re going to be talking about the tourism industry in the Bahamas and how it has been shaped by its history and some of those colonial influences.

Emily: That’s right. And we’re going to be talking about how the discourses surrounding this tourism have shaped Bahamian identity up until now.

Katrina: We recognize this is a complicated issue, but it’s not all about slavery and colonialism. There’s a lot to be learned and a lot of hope for the future. And while we’re looking at the Bahamas as a case study because it’s an area we both visited and are particularly fond of, these issues are certainly not limited to the Bahamas.

Emily: Right, every place is different and has its own unique characteristics and history, but tourism is a major global industry. It’s a particularly important part of the economy for a lot of these small island nations that have complicated colonial pasts.

Katrina: And if you can’t tell, trying to understand the Bahamian experience is especially complicated because Emily and I are white Americans. So the struggle is how to juggle these concepts while realizing you are coming from a different privileged opinion.

Emily: The reality is we’re American and not Bahamian, so we really can’t speak to what it’s like to be a Bahamian. At the same time, it’s important for us to think about these things because the past isn’t going away and we all need to muddle through these complicated realities. And as tourists and visitors, perhaps if we can attempt to understand these complex issues and bring them to light, we can move toward a future that at least starts to move away from these negative colonial influences.

Musical interlude

Emily: I went to Andros Island as a tourist like most other people who visit. Although compared to Nassau, Andros is remote and sparsely populated island, and I stayed in a family owned Eco Resort, I was on vacation, and I fell in love with the blue water and the diving just like many visitors. But after a few extended stays, I started to become aware of this very different reality of tourism in the Bahamas and its colonial ties.

Katrina: As white Americans, we don’t always realize the privilege we hold in our ability to come to the Caribbean for a vacation and see these locations as escape from reality. I had a similar experience to you. When I visited the Bahamas, I stayed on the small island of San Salvador and resided in the Gerace Research Center. Even though it was an old Navy base with no A/C, and my time was spent more studying than relaxing, I was still a tourist and didn’t come to these realizations until long after my stay there.

Emily: So both Katrina and I have wonderful experiences as tourists in the Bahamas, but we recognize that tourism is pretty complicated, and we just want to make clear before we start that we really have a love for this country and a profound respect for the people who live there.

Katrina: So for today’s podcast, we’re going to be looking at the literature to enhance understanding that we developed as visitors by diving into the research that’s been done on tourism in the Bahamas. And while we have limited knowledge as foreigners, we hope that we can do the topic justice and spark a conversation by muddling through these issues.

Emily: So before we dive in, we wanted to give some brief geographical reference. The two most populated islands in the Bahamas are New Providence in Grand Bahama. New Providence is home to Nassau and Paradise Island which contains the large megaresort such as Atlantis that most Americans think of when they picture the Bahamas.

Katrina: But the Bahamas is 30 populated islands in total. The islands other than New Providence and Grand Bahama are known as the Out Islands, also called the Family Islands.

Emily: And even though the majority of tourism in the Bahamas is on New Providence in Grand Bahama, there are a lot of other kinds of tourism on the other islands as well.

Katrina: Tourism is also really critical to the economy of the Bahamas, which is home to about 395, 000 people, according to the UN. Compare that with over half a million people who visited the Bahamas in 2018 alone. And according to Tourism Today, about 50% of Bahamians work in the tourism industry.

Emily: So with that in mind, let’s take a look back at some of the history of tourism in the Bahamas. And there’s a lot to get through here, so bear with us as we try to speed through it.

Sound effect

Emily: Christopher Columbus was the first European explorer to visit the Bahamas, landing on the island of San Salvador in 1492. The Spanish didn’t have much interest in the Bahamas except as a source of slave labor, and they transported nearly the entire indigenous population to other islands as laborers. After the Spanish abandoned the islands and left them unpopulated, the British eventually colonized the area and established permanent settlements. During the 18th century, the British forcibly brought many enslaved Africans to the Bahamas, and their descendants are now approximately 85% of the Bahamian population. Tourism has long been present in the Bahamas, with the British first setting up hotels in the 19th century. However, development was relatively modest until after World War II, when the predominantly white government, attempted to make tourism a mainstay of the Bahamian economy, expanding tourism infrastructure primarily on the islands of New Providence and Grand Bahama. With the introduction of gambling in the 1960s, and the decline of tourism to Cuba as a result of the US embargo after the Cuban Revolution, tourism continued to enjoy massive growth during the 1950s to 1970s.

Sound effect: No, no, …

Katrina: But in the 1960s, major political changes began that would affect the tourism industry. At the time, the Civil Rights movement was in full swing in the nearby United States; and meanwhile, black leaders in the Bahamas also began to work towards securing representation. The Black-led Progressive Liberal Party was formed in the 1960s through a series of meetings throughout the Family Islands, and it became the first true national political party throughout the Bahamas. In 1967, Lynden Pindling, a black Bahamian who was educated in London, was elected Premier of the Bahamas, the Progressive Liberal Party also gaining a controlling share of votes in the Assembly and formed the first black government in Bahamian history. At the time, the Bahamas was still a British colony, but in 1969 its constitution was amended to give the government more responsibility and to change the status to the Commonwealth of the Bahamas with Pindling as the first Prime Minister. The Bahamas officially gained independence from the Crown in 1973.

Emily: Pindling made clear that his party sought economic diversification, moving away from tourism alone as the sole basis for the economy. We hear Pindling talk about this in this clip from the Harry C. Moore Library at the University of the Bahamas:

“What is the policy of your party?”

“Economically we should like to use our country area so that we can attract more foreign capital to set up light industries here, for the exports to the central South American Caribbean areas so that we can create more employment. We do not feel that tourism is too healthy a project to have it just alone – tourism along with something else, yes, tourism alone no.”

Katrina: One aspect that made tourism somewhat problematic was leakage of tourism revenues. Leakage is used to refer to the revenue from tourism that is lost to other countries’ economies; and it is a common problem with tourism development in many destinations, particularly when much of the development is driven by foreign investors. The focus of development at the time was achieving greater self-reliance through national ownership – a common developmental strategy at the time. Unfortunately, however, these efforts coincided with some serious economic challenges in the Bahamas and throughout the world. In the early 1980s, the oil crisis plunged the world into recession, and many of the new hotel rooms, having been built in the 1970s, were left empty. By the late 1980s, the average occupancy of hotel rooms in Nassau was at an all-time low of only 52%.

Emily: When a new political party and a new Minister of Tourism took over in 1992, the government decided to get out of the tourism business and began selling resorts to foreign development companies. This privatization strategy led to what has been called a renaissance of the tourism industry in Nassau as hotels were refurbished and updated. Similar development was seen in Grand Bahama, although these changes occurred more slowly. Bahamas first began to consider eco-tourism and sustainability of the tourism product in the mid-1990s, and several smaller, more environmentally friendly hotels were constructed. Most of these were geared toward bonefishing, a type of primarily catch and release sportfishing that is popular in the salt flats of several Out Islands, as well as certain areas of Grand Bahama. However, development in the Out Islands remained modest. Air travel to the Out Islands was limited and mass tourism remained the primary source of revenue for the country.

Emily: So how do we think about colonialism in relation to tourism? Well, for one thing, we see a history of racial segregation related to the tourism industry.

Musical interlude

Emily: Catherine Palmer, a researcher from the University of Brighton, wrote about this in a 1994 article. She describes how, particularly in Nassau, there were areas that were off limits to Bahamians and even the Out Islands were segregated with the whites having more control. Palmer is not the only scholar to write about these issues. In her 2019 book Destination Anthropocene Amelia Moore describes the so-called “Isles of June” narrative that shapes this type of tourism. The term “Isles of June” was originally coined by Christopher Columbus, and this narrative shows how these colonial views of an island paradise continue to shape the identity of the Bahamas, Bahamian people, and even the tourists who visit. In the “Isles of June,” Moore writes, “the white guest is always right, the black native server is always cheerful, the weather is always warm, and there is no reason to worry about histories of racial subjugation, corrupt local politics, or the uneven impacts of tourism. In the “ Isles of June,” foreign investors build large hotel complexes on coastal property, clearing the bush and cleaning the beach of flotsam; in the “ Isles of June,” many Bahamian citizens aspire to good hotel jobs and the tourism sector is promoted by the government as the engine of local employment. Bahamians live to serve.”

Musical interlude

Emily: While we place these things in the historical context that underlies this narrative, it is not restricted to the past. This narrative remains dominant in this type of mass tourism today. For example, I found a real advertisement for Paradise Island, which is home to Atlantis and several other big resorts, that really plays up the colonial history in trying to draw visitors. They emphasize the fact that the language is English and they drive on the left-hand side of the road and discuss the fact that the Bahamas was a British colony until 1973 instead of anything post-independence. They talk all about the British influence as a source of convenience for these tourists, and then they mentioned the African culture purely when it comes to outfits and drum shows for entertainment. They show black Bahamians dressed up in elaborate costumes, dancing, or acting out roles as rum runners or Pirates, or their white glove uniform servants, opening doors and attending to the predominantly white tourist needs.

Katrina: Right, so the tourism products we often see being promoted in terms of Nassau is this vision of black Bahamians either catering to white guest or dressed up in a way that is consistent with the stereotypes that visitors already have. These advertisements illustrate Katherine Palmer’s point that colonial legacies have really shaped Bahamian identity. Palmer makes the point this colonial history is what is taught in schools even after independence, but obviously there is way more history involved here. A quote using the Palmer paper that really ties this together is: “We studied British history, British civilization, and even British weather, but what about ourselves? We have no past. And under colonialism, no future.”

Emily: Palmer also talks about how these brochures and other ads alter myths and traditions in order to attract tourists. And think about the implications for that. So now you have Bahamians working for these resorts and playing into these depictions to keep tourists coming back. And Palmer uses a quote that I think really helps get to the Bahamian perspective on this: “For decades, destinations like the Bahamas have been saddled with images of smiling natives, often shirtless, shuffling under Limbo bars with frothy fruit and rum drinks to the delight of the world jetsetters. How far from the truth this is?”

Musical interlude

Katrina: So let’s talk about whether or not these advertisements actually are far from the truth. After all, it’s important to remember that this paper’s from the 1990s and a lot of change since then; plus one paper doesn’t tell the whole story.

Emily: So to get to a different perspective on this issue. We talked to my friend Tarran Simms, who I met during my time on Andros Island. Hey Tarran, can you introduce yourself for our listeners, please?

Tarran: So my name is Tarran Simms. I work with the Bahama’s Ministry of Tourism, in the Sustainability Department. My focus is community-based tourism and climate change issues pertaining to tourism.

Emily: Can you tell me what it means to you to be a Bahamian?

Tarran: Personally, for me I am one who is really in touch with culture. So it’s the way we talk, the way we eat, the way we greet people, the way we just protrude that energy; also our loudness, we’re very loud people. We can be aggressive sometimes also, but our aggression isn’t violent aggression. There’s more, you know, this is how we are. So, I embrace those aspects of our culture. I love the Bahamian dialect thoroughly. It was something that was looked down upon and still looked down upon, but I embrace it. I love the food. And I love our colorfulness. You know I love the colorfulness. We’re very colorful people. I love that it, it’s what makes us different, you know.

Emily: Yeah, and when you said that the dialect is something that’s looked down upon, can you tell me what you meant by that?

Tarran: Well, back in the day we had a lot of British teachers here, and it was always the Queen’s English. You had this book, the Queen’s English, and a lot of people they look down on the dialect, and when you spoke the dialect, that meant that you were from the inner city. You know you’re from the ghetto, the poor impoverished areas. But you know, I gained a great appreciation when I went to University. So I did a Bahamian dialect course, and she was able to bridge the connections between the slaves trade and which slaves came to the Bahamas. And that’s when I was like, “that’s who we are, but Bahamians.” We don’t embrace our dialect at all. So I made it a point when I’m speaking Bahamian to Bahamian, I use my dialect.

Emily: So we heard Tarran talk about his view of the many aspects of the Bahamian identity, such as the vibrance of the people and the importance of dialect, but we do hear some remnants of colonialism in Tarran’s account of his own experiences, with the older generation insisting on the use of the Queen’s English. The younger generations, on the other hand, used language as a way of reclaiming their identity for themselves, and we wanted to get into how the Bahamian identity relates to tourism so we asked Tarran about that.

Katrina: A lot of Euro-Americans come to the Bahamas with this, I guess, stereotypical image of Bahamians in their head like they go with the flow, they drink rum, they dance and wear, you know, colorful clothing.

Tarran: Tell me about it.

Emily: But yeah, I thought you know, the advertisements that you see of people dressed up in costumes and, you know, this very stereotypical views.

Katrina: And if you could just expand upon aspects of Bahamian culture that most of Euro-Americans don’t know about.

Tarran: Most definitely. OK. I’ll give you an example in Andros. I have like a friend he was staying with me and we were in Andros and we came over to Nassau and like three days into the trip he said. “Well, I didn’t know the Bahamas was this, you know, had this much development.” And you know, I always try to show people like anywhere you go in the world, you go in the U.S. you have sections that are rural – rural areas — and then you have areas that are much more developed. Go back to the point about Americans like thinking that we’re all dance and it’s a vacation destination. We always have to tell them like in order for this this baby to run, somebody has, it’s like a swan, somebody has to be kicking the legs for it to be staying afloat. We work our ***** off to show that, you know, our tourism product is top of the line. We are on top of our game globally, because we’re not just competing with our regional partners anymore. We’re competing with everybody. In the Ministry of Tourism, I’ve gained a better appreciation for the work that they do. We have, even up to the big resorts, we saw that they even they break ground, we do a sustainability report on them. So, we do due diligence. I mean, you know, we’re small island nation. Most small island nations, when you look at them, tourism is the main thing because they’re very strapped for resources, and tourism is the easiest things for them to exploit and explore. If you work hard to keep this baby afloat.

Emily: Yeah. And so do you think that that importance of tourism affects the Bahamian identity and the way that it’s expressed?

Tarran: Most definitely! You know when we first started up with our ads, it was all about jumping on Goombay. That colorful perception came from those historical ads. But now if you look at our commercial offerings now, we’re transitioning into more chic. Our main target market is the luxury market. When you look at our ads now, it’s moved away from that kind of colorful appeal to a more chic… We’re still dancing of course, But it’s but, you know, they’re also encompassing recently more eco-activities in those ads. And so, moving away, but that image of the Bahamas which depicts that colorful person dancing and singing and having a good time. It’s still there. And as I said before, when it came to the Bahamian culture, that is who we are. We are colorful people.

Katrina: So in Tarran’s view, that traditional view of colorful Bahamian culture does accurately reflect who they are. But he also mentioned the shifts to new forms of marketing and new types of tourism. So we asked him to expand on that.

Emily: So you talked about new kinds of marketing and how the marketing is expanding into other kinds of tourism. Can you tell me a little bit about where you see new forms of tourism going in the future in the Bahamas?

Tarran: So right now we’re working on a big community-based tourism project, so just this past Sunday, I submitted a proposal for our grant for four hundred thousand dollars to develop more community-based activities, looking at the adventure tourism market, the nature-based tourism market, and the health and wellness tourism market. We find that these sectors are more easier for locals to get into; it doesn’t require a high cash output, I mean on the surface. And when I was in high school that was 2008, the Bahama’s Ministry of Tourism launched this campaign to create a sixteen-island destination. So instead of saying come to the Bahamas, you’re saying come into Andros. We want people to come here to have a multiple destination experience, and we’re trying to sell the culture of each island. And so with this project that we’re doing with community-based tourism, it would help to create a brand for Andros and also help to strengthen community-based businesses, and also help to find capital for people to go into community-based businesses in tourism in Andros. It’s a lot of marketing work, a lot of capacity building work. So, I’ll be hosting workshops not only in Andros, but throughout the Bahamas on community-based tourism. I’ll be carrying along with me the Bahama’s Development Bank, the Bahama’s Small Business Development Unit, and a marketing professional to teach businesses, like small businesses in the tourism sector, about how to manage their finances, how to do their marketing, and also about CBT and how it should operate. And so, we are doing this because, one, socially it helps to increase the socioeconomic statuses of small rural communities. But also, we notice that the, the global trend in travel – people want more authenticity. You know people no longer want to come an experience a destination; they want to be a part of the experience, they want to make that experience with you, and the only way you can do that is through sharing the culture. And so that’s why we’re embracing CBT, because our community-based tourism, to get this and to, to actually give the market what they want.

Emily: What kind of opportunities do you see that kind of new form of tourism creating for some of these local communities?

Tarran: Most definitely more cash and connection. With community-based tourism, the studies have shown that most of the cash spent stays within the community. When you look at the mass tourism model now, especially in Andros, not Andros, sorry, in Nassau, there are big leakages because most of these companies are owned by foreign direct investors, and so a lot of the money goes back out of the country. And also the stat in the Caribbean, right now, when it comes to managers in the tourism sector, a lot of these big corporations bring in their own managers. But when we look at the overall payout for payroll, forty-five percent of that goes to foreign managers in the Caribbean in the tourism sector. So CBT would help, one, to keep more of the money inside the community and to ensure that the Bahamians are not only working in the industry, but are actually owning the industry.

Musical interlude

Emily: So we heard Tarron talk about how tourism marketing is now focusing on some of the more remote islands and the unique experiences that they offer. Moore talks about this in Destination Anthropocene as well. She describes how the depopulated aspects of these islands are being promoted as what she calls a green destination amenity. She describes the marketing vision as a dream of ecologically mediated tranquility.

Katrina: But it’s important to remember that even in this type of tourism, we continue to see narratives that are reminiscent of the colonial past. For example, Helen Gilbert wrote an article in which she particularly pointed out the ways that ecotourism actually continued to promote these colonial legacies. For example, ecotourism promotes the idea of a pristine, isolated, remote or unspoiled environment that reflects a wilderness excluding human activity. There is a rhetoric of discovery, expedition, exploration that is reminiscent of the legacies of conquest in the colonial past.

Emily: Yes, and we definitely see this in the tourism product being offered in the Bahamas as well, particularly with respect to Out Islands tourism. Moore describes how this type of tourism is promoted through what she calls the “ephemeral islands’ narrative.” As she describes, the “ephemeral islands” are the domain of naturalists and environmental educators who are intensely focused on maintaining the diversity of island species and informing the public about their natural heritage. Moore goes on to state that in the “ephemeral islands” the Bahamian citizens are assumed to be largely unaware of the natural wonders that surround them.

Katrina: When you look at the way the Out Islands are promoted, we definitely see where that narrative that Moore talks about in the colonial legacies and that Gilbert highlights, comes into play. The advertising does not focus, for the most part, on the people.

Emily: But there is another side to that coin as well, which Tarran pointed out. The focus on individual islands allows residents of the Out Islands to reclaim their identities and showcase their individuality for the rest of the world.

Katrina: Earlier you were talking about marketing the individual islands. Can you talk about how different each island is and if you can tell people are from different islands?

Tarran: Most definitely. The thing in all aspects of the social realm, when you look at the way we cook: Cat Island cooks different than Nassau, Nassau cooks different than Andros. The way we speak: when you go to Cat Island, I can’t even understand them because they are so deep into the dialect. They do reef reconstruction in Cat Island. In San Salvador if you want to do deeper dives, go to San Salvador. Andros, you can dive on the Great Barrier Reef, and Bimini can go deep sea fishing. In Abaco you can go see one of the world’s last, I mean, oil primed lighthouses. So, each island has different historical aspect. Each island has the communities operate differently. So you have so much different experiences. Well we have 700 islands, but only sixteen islands developed for tourism.

Emily: So do you think that these new community-based forms of tourism will affect the way that Bahamians on various islands are able to express their own cultural identity?

Tarran: Most definitely, and I think we would be able to gain a better appreciation of the individual islands. A lot of the Bahamians haven’t even traveled throughout the Bahamas. Most foreigners probably traveled to more islands that most Bahamians who live in Nassau.

Emily: So while Moore talks about how these tourism narratives shape Bahamian identity, Tarran points out that, in some ways, tourism marketing can also help Bahamians embrace an express their identities. In other words, tourism has the potential for some positive cultural impacts as well. It’s also important to acknowledge that because 39% of the GDP comes from tourism, there are real economic benefits to local people associated with the industry. While Moore’s point is well taken that we should not promote a narrative that assumes every Bahamian wants a hotel job, the fact is that the industry provides well-paying jobs for a number of people.

Katrina: Let’s hear what Tarran had to say about how jobs and tourism lead to new opportunities for many Bahamians, including himself.

Tarran: I could talk about the current generation now. You know, when we look at the tourism school right now at the University of the Bahamas, they probably have the lowest enrollment, but when we look at sectors like medicine and law, they have the highest enrollments. So a lot of Bahamians are venturing away from being more academically trained in tourism, and I think the past years of tourism has allowed for this to happen. And I say that because you know my mother’s father was a taxi driver in the tourism sector. My grandmother worked in the hotel; her mother worked in the hotel. So my grandmother and my grandfather were able to pay for my mommy to go to a technical school that she became in secretarial science. My mother who is in secretarial science, she then was able to work to send me off to University. And then when you when you look at other Bahamian families, like for example, our second Prime Minister both his mother and father works in tourism sector, and they were able to fund his education to become a lawyer. So I think it has allowed for the Bahamian society to become more educated and a lot of Bahamians diversifying their professional lives are moving away from tourism.

Emily: So what we’re talking about is ensuring that people have choices and can shape their own futures.

Katrina: Especially when many agencies involved in developmental programs defined development as allowing people to make conditions under their own choosing. So as you said Emily, it’s about choice, so it makes sense for us to think about whether expansion of new forms of tourism can increase the choices available.

Emily: And as we heard Tarran say, we’re seeing more and more Bahamians seek education in other sectors like medicine in the law, and he credits tourism with their ability to do that. So in that sense, tourism has really is increased the choices available.

Katrina: So while there is still the remnants of colonial influence, there are a number of ways in which Bahamians are empowered to take control of their own histories to continue today. Aside from what Tarran talked about, as Moore points out, Bahamian writers and artists like Marian Bethel whose poem read earlier are speaking out about the injustices of globalization and helping to reimagine their own conditions. Moore says by shedding light on the colonial and racist past, local Bahamians can expand their opportunities in the tourism industry and scientific careers.

Emily: So perhaps these shifts in the tourism industry can mean that Bahamians will have more agency and how they participate in and guide the tourism industry. Or even depart from it to explore other industries, because the income from tourism leads to more opportunities for education in other areas. For example, as we heard Tarran say earlier, the Ministry of the Bahamas is really focusing on community-based tourism initiatives to provide those new opportunities within the tourism sector itself.

Musical interlude

Emily: Earlier we heard Lynden Pindling say that the Bahamas should not rely on tourism alone for its economy, but should find other sources of growth as well. And from what we heard Tarran talk about, we hear how the ministry is still working to try to diversify the economy today. And in Tarran’s view tourism has given Bahamians opportunities to expand into some other industries.

Katrina: Although we looked at the Bahamas as a case study, it’s important to remember that these issues are present in a lot of places, particularly in the Caribbean.

Emily: Right, the reality is that many places are affected by post-colonial legacies and ties to the tourism industry. So while certainly each place is unique, these types of complex issues are not restricted to the Bahamas alone. Many islands within the Caribbean in particular, are struggling to find this balance between tourism and livelihoods within other industries, but at the same time, it’s important to remember that each location is different and no one size fits all form of tourism will be appropriate for anyone destination.

Katrina: Although we didn’t quite have the time to unravel everything today, we hope that we at least started a conversation and new perspective about tourism colonialism. I’d suggest checking out our references if you want more details about any of these topics. And a big thank you to Tarran for sharing his time and speaking with us about these issues.

Emily: And thanks to Ariel Seymore for reading Marion Bethel’s beautiful poem. I think that this conversation has shown that tourism is a tricky thing. On the one hand, we see the colonial remnants still present today. Bethel says in her poem that Bahamians live on a tourist plantation and don’t even know what they have lost. And in Palmer’s paper we saw a similar sentiment that under colonialism, Bahamians have no past and no future. Yet at the same time, we see efforts to reclaim Bahamian identity and forge paths into new kinds of tourism. And we heard Tarran talk about how tourism has expanded opportunities for many Bahamians. Just like anywhere, the people of the Bahamas work hard in the hopes of a better future for themselves and for future generations.

Emily: As Oscar winning Bahamian actor Sidney Poitier once said: “My mother is a Bahamian. My father is a Bahamian, as am I… And all that I am, I’ve received from them and a country that has today given me the opportunities, and to my grandchildren, that I have never dreamt of.”

Musical interlude

Lisa: We hope you enjoyed today’s episode of Seas the Day. Visit our website to learn more about this week’s episode, including how to find more poems by Marion Bethel. We’ll have more on tourism in upcoming episodes of the podcast.

Today’s podcast was written and recorded by Emily Melvin and Trina Rosing. Rafa Lobo edited the podcast.

Our theme music was written and recorded by Joe Morton.

Follow us on Instagram and twitter at seasthedaypod

And visit it our website at sites.nicholas.duke.edu/seastheday

If you enjoyed this podcast, we invite you to leave a review in iTunes. Help us extend our reach beyond our friends and family!

We would be most grateful.

END OF TRANSCRIPT

Bethel, M. (2008). On a Coral Cay. Black Renaissance, 8(2/3), 165.

Bounds, J. H. (1978). The Bahamas tourism industry: Past, present, and future. Revista Geografica, 88, 167–219.

Cleare, A. B. (2007). History of tourism in The Bahamas: A global perspective.

Gilbert, H. (2007). Ecotourism: A colonial legacy? In Five emus to the king of Siam: Environment and empire.

Moore, A. (2019). Destination Anthropocene: Science and tourism in The Bahamas. University of California Press.

Nassau Paradise Island. (2013). Nassau Paradise Island, Bahamas History and Culture. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YmXLXQ3anfA

Nixon, A. (2015). Resisting paradise: Tourism, diaspora, and sexuality in Caribbean culture. University Press of Mississippi.

Palmer, Catherine A. “Tourism and Colonialism: The Experience of the Bahamas.” Annals of Tourism Research, 4th ed., vol. 21, Elsevier Science Pergamon, 1989, pp. 792–811.

Statistics. (n.d.). Tourism Today. Retrieved January 16, 2020, from http://www.tourismtoday.com/services/statistics

Tourism History. (n.d.). Tourism Today. Retrieved January 16, 2020, from https://www.tourismtoday.com/about-us/tourism-history

University of the Bahamas. (n.d.). Pindling Radio Cut #1. Retrieved February 7, 2020, from //cob-bs.libguides.com/HCML/LOPRoom