|

|

|

Each fall, most North American birds embark on a southward migration to escape harsh winters, returning north in the spring. While some species travel as far as Central and South America, others remain within the continent and call Durham their wintering home. Unfortunately, collisions with man-made structures represent the second largest threat to migratory birds, trailing only behind predation by cats. It is estimated that these collisions cause between 100 million to 1 billion bird deaths each year in the United States alone (Klem Jr. 1979, Loss et al. 2014). These figures are likely underestimated, as window strikes have not been thoroughly quantified across much of the country. By addressing this issue, we have the potential to protect a significant number of birds, and everyone can contribute to this effort.

Situated along the Atlantic Flyway—a vital migratory route taken by many birds—Duke University is ideally positioned to make an impact. Our informal censuses, combined with the efforts of dedicated Duke students and researchers, indicate that window strikes are indeed a concern for birds on our campus.

How Will We Solve This Problem?

To effectively mitigate this issue, it is essential to identify which buildings pose the greatest risks to birds and to quantify the number of collisions, including the species affected. Armed with this data, we will collaborate with Duke administration to install bird deterrents on existing buildings and ensure that all new constructions are designed to be bird-friendly.

Discover how Duke students are actively working to protect birds and join our initiative to make Duke a more bird-friendly campus. Visit the Bird-window Collision Project at Duke site for more information on the history of this project.

See the publications that have resulted from this work:

Elmore, J. [et al. including Cagle, N. L.]. 2020. Correlates of bird collision with buildings across three North American countries. Conservation Biology. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13569

Winton, R. S., Ocampo- Peñuela, N., and Cagle, N. L. 2018. Geo-referencing bird-window collisions for targeted mitigation. Peer J 6:e4215 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.4215

Hager, S. B., Consentino, B. J. [et al. including Cagle, N. L]. 2017. Continent-wide analysis of how urbanization affects bird-window collision mortality in North America. Biological Conservation 212: 209-215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2017.06.014

Wittig, T. W., Cagle, N. L., Ocampo- Peñuela, N., Winton, R. S., Zambello, E., and Lichtneger, Z. 2017. Species traits and local abundances affect bird-window collision frequency. Avian Conservation and Ecology 12(1): 17 https://doi.org/10.5751/ACE-01014-120117

Ocampo-Peñuela, N., Winton, R. S., Wu, C. J., Zambello, E., Wittig, T. W., and Cagle, N. L. 2016. Patterns of bird-window collisions inform mitigation on a university campus. PeerJ 4:e1652 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.1652

Bird-Window Collision Project at Duke

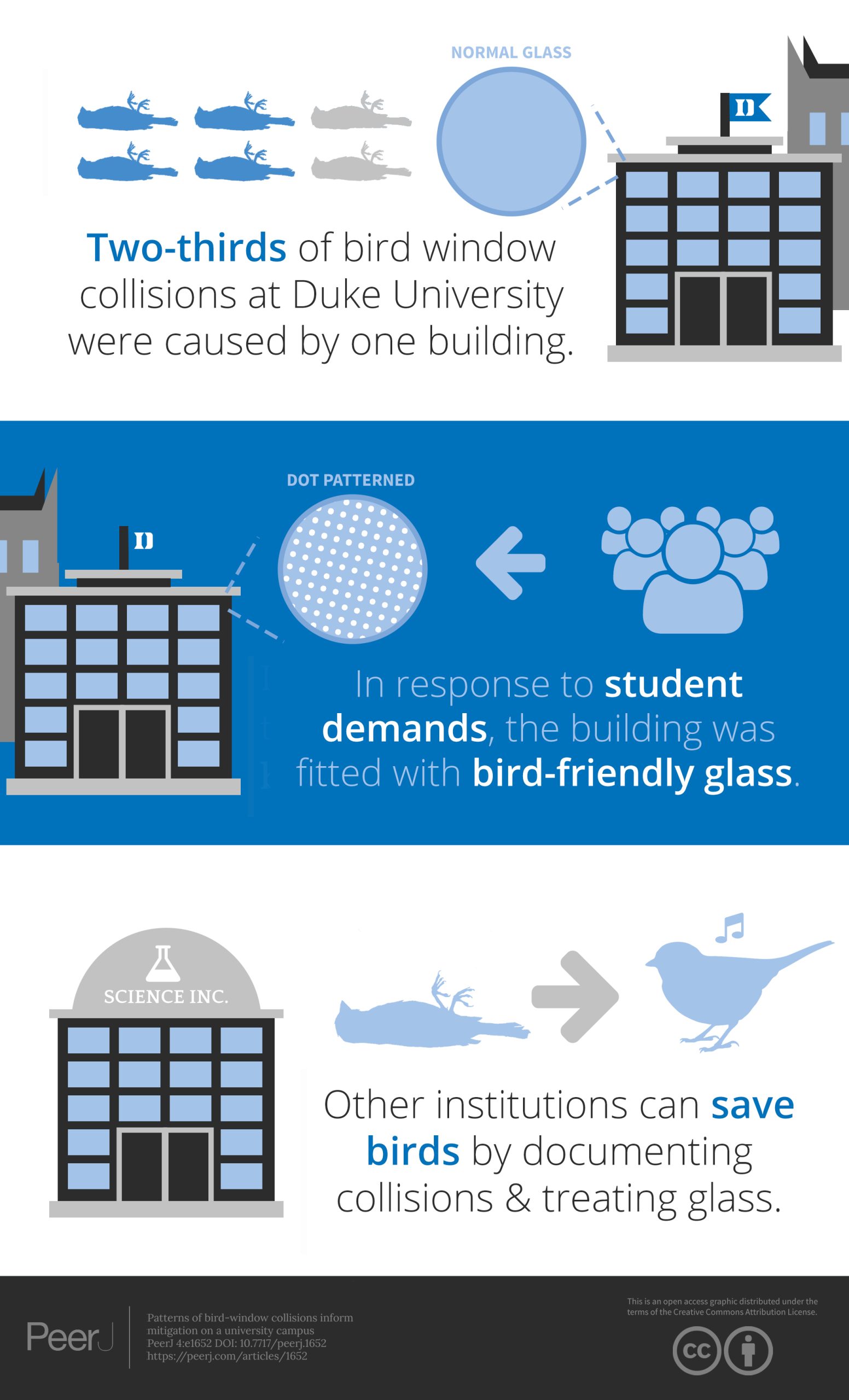

The Bird-Window Collision Project at Duke University addresses the critical issue of bird fatalities caused by window strikes on campus. Over a decade ago, this initiative was launched by Natalia Ocampo-Peñuela, then a PhD student at the Nicholas School of the Environment (NSoE), in response to growing concerns about bird mortality due to campus buildings. The project aimed to estimate the number of birds dying from collisions, identify high-risk buildings, and propose solutions.

Today, the project is led by Dr. Nicolette Cagle, an ecologist, naturalist, and Senior Lecturer in the NSoE who teaches several natural history courses. Graduate and undergraduate students volunteer to support the project, with data collection conducted annually during the spring migration season by students in the Wildlife Surveys course (ENVIRON 706). Together, the team continues the effort to understand and mitigate the risks posed by campus architecture to migratory birds.

Duke Assessment

Currently, we are surveying six buildings on Duke’s West Campus to identify which structures pose the greatest risk. These surveys take place during peak migration periods in April and October, where volunteers conduct daily checks for bird carcasses over a 21-day period. We also rely on informal, year-round reports from students who discover birds near other campus buildings. Our goal is to better understand the scale of bird-window collisions and to work towards practical solutions that minimize these tragic incidents.

Duke University was proud to participate in a North American-wide bird-window collision assessment, a collaborative project led by Augustana College professors Steve Hager and Bradley Cosentino. This initiative brought together universities across the continent to assess bird mortality on campuses. In 2014, Duke joined 19 other campuses in this effort, with Duke at that time being the only participating campus in North Carolina. Located along the Atlantic Flyway, one of the major migratory routes in North America, Duke’s participation is particularly important in understanding how migratory birds are impacted by window collisions in our region.

Mitigation. After completing the assessment of bird deaths and identifying high-risk buildings, we have and plan to continue to collaborate with the Duke administration to implement bird deterrents and reduce collisions. These deterrents will be essential in making our campus safer for migratory birds. Learn more about strategies to prevent bird-window collisions and support ongoing mitigation efforts through resources available on leading bird conservation websites.