David Rosen: Federally-Insured Energy Savings Performance Contracts (ESPCs)

Building retrofits provide an excellent opportunity to reduce greenhouse gas emissions domestically in an economically advantageous way. Emissions from buildings represent approximately 15-18% of total greenhouse gas emissions in the US.[1] Retrofitting buildings by switching to LED lighting, improving HVAC systems, and tightening building envelopes and insulation reduced the GHG emissions from buildings by an average of 11% in 2010, and many experts believe that number can be pushed as high as 30%.[2] More importantly to many politicians, investing in retrofits would save up to 50 dollars per metric ton of CO2 equivalent (CO2e) abated according to the consulting firm McKinsey & Company.[3] Based on the United States total emissions of 6.742 billion metric tons CO2e in 2013,[4] this estimate means that up to 15 billion dollars could be saved between now and 2035 if a mass retrofitting program in the United States was developed.

Several deterrents exist for commercial or residential business owners deciding whether to retrofit their buildings. It often takes 10-20 years to recover costs and return a profit, but only half of all home owners in the US stay in one home for at least ten years.[5],[6] As for commercial buildings, two of the three main types of commercial building leases, net leases and modified gross leases, have tenants pay for their own utility bills.[7] With these leases, the landlord would be responsible for deciding to retrofit and paying for the retrofit but would not see any profit from the reduction in utilities.

However, a financial model exists that bypasses the upfront costs associated with retrofits and provides immediate profits to the building owner. The federal government uses Energy Savings Performance Contracts (ESPCs) to finance retrofits of government buildings such as prisons, statehouses, and administrative buildings. The Department of Energy explains:

“An ESPC is a partnership between a federal agency and an energy service company (ESCO). The ESCO conducts a comprehensive energy audit of federal facilities and identifies improvements to save energy. … The ESCO guarantees that the improvements will generate energy cost savings to pay for the project over the term of the contract (up to 25 years). After the contract ends, all additional cost savings accrue to the agency.”- Energy.gov[8]

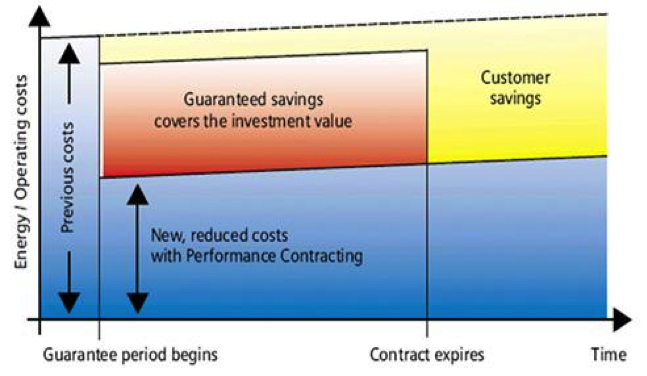

What makes ESPCs truly innovative is the payment structure, modeled below.[9] The bill paid to the ESCO is based on a percentage of the energy costs saved given the building’s initial energy consumption and the current price of energy. Therefore, the ESCO gets paid more quickly if the retrofits are more successful, and the investor still sees profit from day one.

However, this leaves two logistical issues, which are the bases of the policy proposed below: who would protect the ESCOs from consumer defaults, and why would a residential homeowner agree to pay the ESPC if they plan on moving and paying a separate energy bill?

A federal ESPC-insurance administration should be developed to encourage residential and commercial retrofits, modeled after the Federal Housing Administration’s mortgage insurance program. Started in 1934, the FHA is entirely self-funded, using the proceeds from insurance payments to pay its staff and to pay off the mortgage lenders in case of homeowner defaults.[10]

Under the Department of Housing and Urban Development, the new administration would insure ESPCs issued to commercial and residential building owners by Department of Energy-approved ESCOs. The policy creating this administration would also make ESPCs and their insurance policies tied to the building rather than the original building owner. Therefore, the owner of the building, whether that be the original investor or a new owner, is always responsible for continuing to pay the ESPC. Since the combined bills from the ESCO and the energy company should still be equal to or less than the energy bills without the retrofit, this shouldn’t be a deterrent to buying or selling buildings with an ESPC.

This program should making issuing ESPCs to building owners relatively risk-free, which opens up new markets for ESCOs, allowing them to expand and spend money researching new energy-efficient technologies. It should save building owners money over the long-term that can be reinvested into society. It may also raise property values thereby increasing property taxes, which could catalyze new investment into cities. Hopefully, this idea will catalyze large-scale promotion of the administration from local governments and large-scale participation from large corporations, which should then be picked up by smaller-scale enterprises.

Critics will argue against the development of this administration for several reasons. First, anything that increases the size of government is looked negatively upon by those with libertarian leanings. Second, although the historical data suggests that programs such as this have been successful, this has the opportunity to cost the federal government money if the program is underutilized or utilized by building owners with unstable financials. Third, some will argue that the property value added in areas that retrofit could negatively impact low-income families; it would be wise to monitor usage within demographic and geographic areas to make sure that this policy didn’t create further gentrification in vulnerable neighborhoods.

Annie comment:

Retrofitting buildings to make them greener and more sustainable is costly, but one of the best ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. I took a class titled “Shelter” at Duke last spring, and we frequently discussed the costs and benefits of retrofitting. In a time where the economy is the most important issue within the political sphere, people are unsure of whether retrofitting is the most efficient way to create environmental benefits. Your discussion of economic and political feasibility was helpful when researching the effects of urban sprawl in Atlanta as well. Retrofitting can really benefit certain communities, but it can also price people out of their homes. In New York City, people were placed out of apartments because they could not pay for the increase in rent. A lot more research needs to be done to definitively determine whether or not retrofitting is efficient. Hopefully in the future it will be less costly to retrofit existing buildings. Interesting read!

Kate comment:

I looked into retrofitting during our Congressional Project. As you mentioned, retrofitting can save up to 50 dollars per metric ton of CO2 equivalent. It always seemed to me retrofitting was the obvious thing to do and it would just take time for all the buildings to do so. However, after looking into it more, I realized a large part of the problem. Most buildings force residents to pay the utility bills. However, the building owners are the ones to bear the brunt of the cost. Yet, they do not directly receive any of the benefits. The graph of the Energy Savings Performance Contracts is particularly interesting and allows for subsidies to further encourage retrofits. The issues that David raises are particularly interesting, and I had not thought through them in as depth. This was a very detailed blog post, and I learned a lot. Good job, David!

Josh comment:

David, your blog post highlights an excellent tool that could be utilized to help curb greenhouse gas emissions. As you mentioned, building efficiency and energy use currently represents an area that is ripe for improvement, research, and development, with gains to be had in almost every aspect of construction, powering, and maintenance. I think one issue that comes to my attention most when looking at ESCO expansion is the guarantee of substantially lower electricity bills in order to offset the cost of retrofit. Do the ESCOs mandate certain standards and or guidelines by which improvements in inefficiencies must be met? Furthermore, I think a program such as this should look to incorporate private groups and companies as well. I’m sure private companies exist or will exist that could fund retrofits such as these and look to make a profit off of the continued payments from homeowners.

I do like all of the benefits you mention, and believe that, over time, energy savings will result in money that can be utilized elsewhere and increased property values that will stimulate the economy and local governments where these projects take place. Also, although your post focuses on retrofits, these ideas can easily be incorporated into new developments, particularly high-density developments with a large amount of residential tenants. The cost of the retrofit could be backed by the ESCO, while the large amount of tenants would easily help split the cost and shorten the amount of time it takes to make a return on investment.

[1]Nauclér, T., & Enkvist, P. (2009). Pathways to a low-carbon economy: Version 2 of the global greenhouse gas abatement cost curve. McKinsey & Company, 192. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2010.01.047

[2] Olgyay, V., & Seruto, C. (2010). Whole-building retrofits: A gateway to climate stabilization. ASHRAE Transactions, 116, 244–251.

[3] Nauclér, T., & Enkvist, P. (2009). Pathways to a low-carbon economy: Version 2 of the global greenhouse gas abatement cost curve. McKinsey & Company, 192. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2010.01.047

[4] Inventory of U . S . Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks (2015). United States EPA, 1-559. doi:EPA 430-R-13-001

[5] Nauclér, T., & Enkvist, P. (2009). Pathways to a low-carbon economy: Version 2 of the global greenhouse gas abatement cost curve. McKinsey & Company, 192. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2010.01.047

[6] Emrath, P. (2009). How Long Buyers Remain in Their Homes. Special Studies, HousingEconomics, (2007), HousingEconomics.com.

[7] Cobb, M. (2015). 3 Different Types of Commercial Real Estate Leases. 42Floors. Retrieved March 7, 2015, from https://42floors.com/edu/basics/types-of-commercial-real-estate-leases

[8] Energy Savings Performance Contracts. (n.d.). Energy.gov, Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy. Retrieved March 7, 2015, from http://energy.gov/eere/femp/energy-savings-performance-contracts

[9] Dublin City Council to Tender for first Local Authority Energy Performance Contract. (2015). Codema News. Retrieved March 17, 2015, from http://www.codema.ie/media/news/dublin-city-council-to-tender-for-first-local-authority-energy-performance/

[10] The Federal Housing Administration (FHA). (n.d.). HUD.gov, U.S Department of Housing and Urban Development. Retrieved March 8, 2015, from ttp://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/HUD?src=/program_offices/housing/fhahistory