This episode explores the topic of food sovereignty using the case study of Palestine. Tasneem and Porter examine the different elements of food sovereignty that can be seen in the Palestinian Keffiyeh and how they manifest in Palestinian’s culture and their economy. Finally, they look at policies that currently restrict those elements of food sovereignty. Part of the Conservation and Development Series.

Host

Tasneem Ahsanullah recently completed her Master of Environmental Management degree, specializing in coastal environmental management. Her Masters Project is a ‘A Global Assessment of Equity in Marine Protected Areas.’ Tasneem studied Biology with a focus in marine & freshwater sciences and received a certificate in Environmental Sustainability at the University of Texas at Austin. At UT she studied the environmental and policy implications of a proposed desalination plant and the deepening of a ship channel in Port Aransas, TX. After undergrad she studied amphibian diversity in Paraguay and terrapin conservation in Bald Head Island, NC. She is interested in small scale fisheries, coral conservation and community based environmental management. Her hobbies include wildlife and macro photography (Instagram: @tasneemphotography).

Porter Porter is studying Environmental Science and Policy with International Comparative Studies. Porter spent her Spring semester of her junior year at the Marine Lab combining her enthusiasm for environmental research with her passion for international studies. She is very interested in Environmental Justice (EJ) and works as the EJ lead for Duke’s Undergraduate Environmental Union. Last summer, she worked as an Environmental Justice intern for the Environmental Defense Fund.

Series Host

Dr. Lisa Campbell hosts the Conservation and Development series. The series showcases the work of students who produce podcasts as a course project. Lisa introduced a podcast assignment after 16 years of teaching, in an effort to direct student energy and effort to a project that would enjoy a wider audience.

TRANSCRIPT

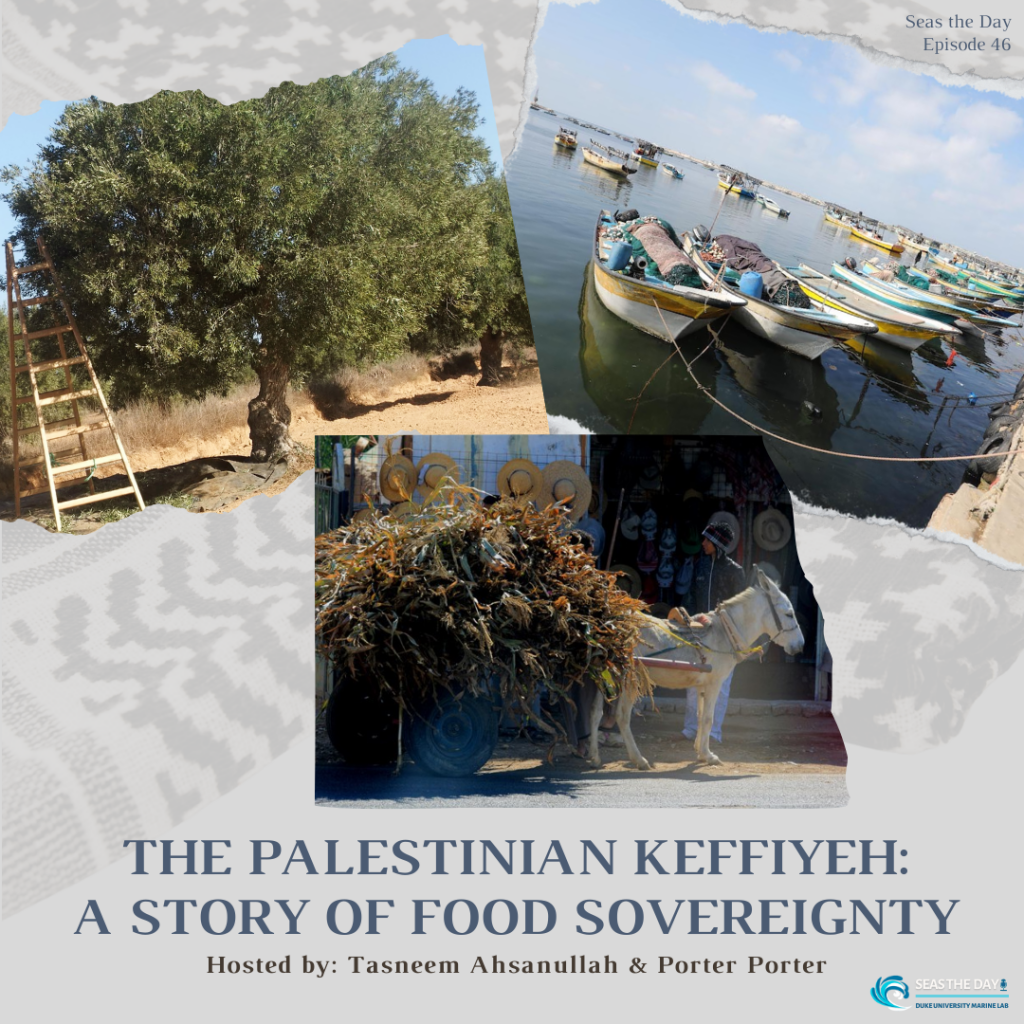

Episode 46 – The Palestinian Keffiyeh: A Story of Food Sovereignty

[Musical intro: oyster waltz]

Lisa Campbell: Hey, listeners. Welcome to Seas the Day. I’m Lisa Campbell, and today we bring you an episode from our conservation and development series. The series features episodes created by students in my conservation and development class, and the students research, write and edit these episodes over the course of just 3 1/2 weeks. I’m always amazed at what they can accomplish in such a short amount of time. In this week’s episode, undergraduate student Porter Porter and master’s student Tasneem Ahsanullah tackled the issue of food security in Palestine. Both students came to my class in January 2024, deeply troubled by the war in Gaza and the resulting human suffering among Gazan civilians. They took the opportunity to learn more about how food security is not just a contemporary crisis tied to the war, but interwoven in the long standing politics of the region. I’ll turn it over to Porter and Tasneem now.

Porter Porter: If you’ve been watching the news lately, you’ve probably seen the countless protests in support of Palestine.

Tasneem Ahsanullah: You may have noticed some of the protestors wearing a white scarf with black detailing. This scarf is called a keffiyeh.

Porter: The keffiyeh is prominent throughout the middle east but the Palestinian keffiyeh has a specific design and is a cultural symbol for Palestinians. It has increasingly been worn outside the region, by human rights activists, politicians, and celebrities, as a symbol of solidarity with the Palestinian people.

Tasneem: But have you paid attention to the patterns on the keffiyeh before? If you’ve never seen the Keffiyeh, picture a white cotton scarf with three distinct patterns: along one edge, thick gray lines at times running parallel and then overlapping, in the middle, pairs of black flowy leaves arranged in rows, and on the other edge delicate interweaving black lines with ovals dotting the intersections.

Porter: There are a few different interpretations of what these three patterns represent, but for this podcast we will focus on an interpretation that centers on food and its importance to the Palestinian people.

Tasneem: The first pattern of the bold lines represents historical trade routes in Palestine and the importance of the region as a hub for trading food, spices, and other goods. Even the famous silk road crossed through Palestine and what is now Israel. It represents a freedom to come and go.

Porter: The second pattern of the rows of leaves on the Keffiyeh represents olive trees, a symbol of resilience for Palestinians. Olive trees are able to grow in a dry arid environment and can live for thousands of years; they can thrive in difficult conditions. To many Palestinains, whose ancestors have farmed the Olive tree since 1200 BC, the olive tree represents their perseverance and connection to their land. Even in the present day, an estimated half of all agricultural land in Palestine is planted with olive trees which links their financial gains with the harvest of this vital green and black fruit.

Tasneem: The final pattern of interweaving lines represents a fishnet, highlighting Palestinian’s connection to the Mediterranean sea and fishing. Fishing is an important part of many Palestinian’s identities and it is a source of pride for fishermen that are able to provide for their families. Seafood is also featured in many Palestinian dishes including Sayyadiy or the “fisherman’s dish” which is chunks of fish fried with caramelized onions, fragrant spices, rice and a savory lemony broth.

Porter: In this episode of Seas the Day, we explore how the Keffiyeh can be read as a story of the importance and power of food sovereignty. My name is Porter.

Tasneem: And I’m Tasneem. As we are making this episode, in February of 2024, news keep breaking on the humanitarian crisis in Gaza and the dangerously low levels of food available. We recognize the urgency of ensuring food security for a starving population, but we are particularly interested in how the Keffiyeh can be read as a story of the power of food sovereignty – which is about much more than securing enough calories.

Porter: So let’s get into an introduction of food sovereignty. But what is food sovereignty? You are probably more familiar with the term food security, which is more about whether people can access food, not about their choice over that food, connection to the food, or control over their food systems. For example, if you look up the definition of food insecurity in the Oxford dictionary it says “the condition of not having access to sufficient food, or food of an adequate quality to meet one’s basic needs.” But increasingly, there’s a recognition that food is important for reasons that go way beyond meeting one’s basic nutritional needs. And that conversation has taken place broadly under the term ‘food sovereignty’ Let’s take a moment to learn more about food sovereignty.

Sovereignty is about power and control, right? In a modern world whose food systems are often globalized, what does it mean for one to have power and control over food? I mean think about the last meal that you ate. Do you know each hand that touched the ingredients on your plate? Do you know where these ingredients were cultivated, or how they were processed? Can you even identify all of the ingredients on your plate? Chances are the answers to those questions are no. I know mine are. Many of us have lost our connection to our food today, and we might not even think about it that much. But for some people – for example Indigenous peoples or rural communities with long-standing agricultural practices and histories — the processes of cultivating, processing, and making their own food is still central to their cultures, communities and livelihoods. Having control and choice over those processes — That’s all part of food sovereignty.

So what exactly does that mean? In 2007, 500 delegates around the world met for the World Forum for Food sovereignty. They chose to meet in Mali, one of the first nations to make food sovereignty a priority through national legislation. In the Declaration of Nyéléni, a document ratified at this forum, food sovereignty is defined as (QUOTE) “the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems.” (END QUOTE)

Let’s break down that definition. First let’s look at the beginning, (QUOTE) “The right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food.” (END QUOTE) Food plays a role in cultures around the world. Often when we picture a place or its people, we picture its food. In an article titled, “Why We Eat the Way We Do”, authors Smith and Brown explain why food has become so important to human identity and also health. For example, the authors describe how when multiple entities in a community are mobilized to produce sustainable, and culturally significant food, people are happier, and healthier. And culturally appropriate food is not only about the end product, but also the means in which different communities produce that food.

Okay, let’s break down the second part of that definition of food sovereignty, that food must be (QUOTE) “produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods.” (END QUOTE) This Declaration of Nyéléni, goes on to say that food sovereignty should prioritize local systems of food production and (QUOTE) “consumption based on environmental, social and economic sustainability.” (END QUOTE) Sustainability is one of the pillars of food sovereignty that the declaration focuses on. Which makes sense, as the declaration focuses a lot on the rights of traditional food knowledge being valued.

In an article by Kuhnlein, the author explains how Indigenous food systems are often more sustainable than the mechanisms of mass production of food that we often see today. In a world that throws away an estimated third of the food that we produce, communities that grow and fish their own food often have a lower environmental impact. But food production that is done locally is not just better for the environment. It empowers communities to be self-sustaining, it makes them more resilient to market fluctuations, and gives them power over their own food systems – which takes us to the last element of the definition, that people should have a (QUOTE) “right to define their own food and agriculture systems.” (END QUOTE) When discussing this, the Declaration of Nyéléni, says that food sovereignty (QUOTE) “… ensures that the rights to use and manage our lands, territories, waters, seeds, livestock and biodiversity are in the hands of those of us who produce food.” (END QUOTE)

So, let’s recap: Food sovereignty is about more than food security. It has a cultural component, because it highlights the importance of food to cultural identity and community building. It has a sustainable/environmental component, because locally produced food that is appropriate to where it’s growing is better for the environment. And then last but not least, food sovereignty is also about the right to self-determination – it is about having control over one’s *own food systems.

Now, can we find those elements in the keffiyeh? Let’s explore the various facets of food sovereignty in the context of Palestine – and the many ways in which food as a tool of warfare is about much more than scarcity. Now, let’s use the keffiyeh to explore the concept and meaning of food sovereignty in Palestine, and think about the way in which food is caught up in the geopolitics of the region.

Tasneem: Part one: Trade routes

Let’s start with the bold lines on the keffiyeh which represent trade routes in the region. Historically, Palestine has been a bustling region with multiple trade routes including the Silk Road. Gaza, the Palestinian territory that borders the Mediterranean, was a trade center that connected Egypt and the Middle East to Europe. Goods like spices, incense, textiles and olive oil moved freely through Gaza, but when Israel gained statehood in 1948 trade in the region was heavily impacted. Some of the impacts resulted from specific policies enacted by Israel to control and restrict the flow of goods in and out of Palestine.

One of the first targets of Israeli law was the family of herbs called za’atar which has been harvested and traded in Palestine since the 12th century. However, In 1977, an Israeli law was passed that designated wild za’atar as a protected plant and made it illegal to harvest za’atar.

This law was put in place due to environmental concerns, but according a paper published by University of Oregon, this law has (QUOTE) “disproportionately negatively impacted Palestinians, leading to debates about the policy’s motivations and efficacy.” (END QUOTE)

Another policy of particular significance has been the Israeli blockade of Gaza which has heavily impacted trade and exports in the region. In 2007, when Hamas was voted into power in Gaza, Israel deemed the Gaza strip ‘hostile territory’ and imposed a land, sea, and air blockade which has been in effect for the past 16 years. The blockade allows Israel to control the food and food related resources moving in and out of Gaza. That has meant a significant loss over a very important component of food sovereignty – control over one’s own food systems.

The loss of control has also resulted in a loss of culturally important foods. According to Gisha, an Israeli human rights organization, one of the foods that has at times been restricted by the blockade in Gaza is sesame seeds. Sesame seeds are often used in za’atar mixtures and other culturally important foods, such as the traditional Gazan red tahini. The restrictions on sesame seed imports caused the price of Gazan tahini to skyrocket. Meanwhile, Israeli made tahini was allowed through the blockade and cost much less so this caused the Gazan tahini industry to collapse.

Sesame seeds aren’t the only food that have at times been restricted in Gaza before. According to Gisha, other items that have been restricted include cumin, ginger, dried fruit, fresh meat and livestock like cattle, chickens and goats. There is also a special class of items prohibited in Gaza called ‘dual use items’ these are items that Israel deems could be repurposed for military use by Hamas. This includes steel bars, concrete, electrical material, pipes and wood thicker than 1 cm. As Gisha notes, many of these dual use items are also used for infrastructure that supports agriculture and fishing. So, the blockade has not just impacted food security but also the infrastructure needed for food sovereignty.

Let’s use what we’ve learned about Za’atar and other traded goods to think about food sovereignty. Za’atar is grown locally, and is an indigenous Palestinian herb that has been farmed for centuries and is culturally important. Also, Za’atar and other foods like tahini have historically been traded in Palestine. However, due to various Israeli policies like the blockade, Palestinian’s do not have control over what they can grow and trade .

Porter: Part two: the olive tree

Remember those beautiful black flowy leaves on the Keffiyeh? Let’s talk about olive trees and their importance to Palestinian culture. They serve as a powerful symbol of resilience that connect Palesetinians to their land and help them support their families.

Laila, a Palestinian representative of Canaan Fair Trade, a company that specializes in producing and selling olive products explains why olive trees are so important to Palestinains. (* https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DANuC1xH3VA) (34 sec)

“Each farmer treats the olive tree as a part of the family like olive trees are from Palestine from ages, 1000 2000 years old and it represent our identity… with those olive trees we say to the world that we belong here as those olive trees as the olive trees belong here. So it represent a Palestinian identity, a Palestinian culture that are so proud of it.”

As Laila mentioned, olive trees live in symbiosis with their Palestinian neighbors who tend to them in exchange for the olives harvested every year.

Writer Wafa Aludani described the Palestinian olive harvest, normally occurring in October, as a community celebration. Generations of Palestinian families gather together to help, mostly harvesting the olives by hand or with tools.

One of the men he interviewed, Abu Jamal explains, (QUOTE) “Every year, we participate in the weeklong harvest festival. We absolutely relish this holiday, enjoying the novelty of meals with our families in the groves.” (END QUOTE)

So, olive harvesting is important to Palestinian culture, but it also supports many economically.

An estimated 100,000 Palestinian families currently (2023) rely on olive trees for income according to an article by Marta Vidal.

As I explained earlier, half of the agricultural land in Palestine is planted with olive trees, almost ten million of them in fact. This is according to an article published in Al Jazera by Mohammed Haddad and Zena Al Tahhan. Most of these olives are turned into olive oil and either consumed locally or exported, primarily to Israel.

As Ghassan Najja, a Palestinian farmer Vidal interviewed described, (QUOTE) “Many farmers rely completely on their olive harvest. It’s our livelihood, our source of life.” (END QUOTE)

But in recent decades, that source has come under attack. In the West Bank, which is an occupied Palestinian territory, tensions between Palestinians and Israeli settlers are high, Israelis have been reported destroying olive trees and attacking Palestinian farmers. Let’s listen to an interview of a Palestinian Olive farmer by reporter Gideon Levy in 2014.

(insert video clip *.07 ~44seconds)

(Translated) “Destroying these olive trees harms the farmers.

They spend their lives taking care of these trees, and then someone just sets them on fire. (.07-.25)

Hundreds of trees have been cut down and set on fire.

(.18 32)

Settlers pass by at any time, cut down and burn our trees as if the trees were their enemy.”

(.40-56)

To understand why this is happening, it’s important to understand why Israeli settlers are living in the West bank. The Israeli government has been authorizing settlements in the occupied Palestinian territories since 1967. According to Amnesty International, this is in direct defiance of international law, however, to date the Israeli government has authorized 150 Israeli settlements in the West Bank. This has led to a total of 10% of Israeli citizens (700,000) living illegally in Palestine.

This large number of Israeli settlers has caused conflict between Israeli and Palestinian citizens. Furthermore, much of this violence like what we saw in the video above is against Palestinians.

And this isn’t an isolated incident. According to a UN report published in November of 2023, attacks from Israeli settlers rapidly increased in the years of 2021, 2022, and 2023.

In that same report, the UN states that (QUOTE) “At the end of November, an initial estimate indicates 800,000 dunums of land have not been harvested due to Israeli settler violence and access restrictions. Many families who rely on the olive harvest risk losing their income for the entire year.” (END QUOTE)

The UN report also calls for a protection of Palestinians and their olive trees from settler violence.

Recall two of the aspects of food sovereignty we mentioned earlier, culture and control.

By destroying these olive trees, the Israeli settlers are attempting to remove Palestinian symbols of resilience and connection to the land, along with important traditions like the annual harvest that brings families and communities together. These are all vital aspects of Palestinian culture surrounding food and its production.

And, not only are these cultural ties under attack, Palestinians control over the use of their land and resources is also being removed. But symbols are important for a reason, and food is more than a trade.

Tasneem: Part three: The fishnet

Tasneem: The fishing net pattern on the Keffiyeh represents the importance of fishing to Palestinians and particularly Gazans that live along the Mediterranean sea. Fishing is not just a way for people in Gaza to make a living and provide food for their families, but it is also an important part of their culture and history.

Laila El-Haddad, a Palestinian author of the award winning cookbook “The Gaza Kitchen”, describes fishing with her grandfather and explains why fishing is important to her:

https://nowthisnews.com/news/watch-how-palestinian-food-identity-and-heritage-is-targeted

(0:36-1:00)

“El Haddad recalls going on fishing trips with her dad and cooking their catch Gaza style he would take me with him on a regular basis to go deep sea fishing for grouper amongst other things I would catch crabs with a flashlight in a net and he would show me how they would prepare them in Gaza clean them out rinse it off and then stuff it with a mixture of mashed garlic red chili paste that Gaza is famous for parsley and then grill them.”

As Laila’s story shows, fishing is an activity which is passed on through the generations in Gaza. However, since 2007 fishing in Gaza has been heavily impacted by an Israeli naval blockade of Gaza’s Medditerranean coast. The naval blockade restricts how far fishermen can go out to fish and if fishermen get too close to the blockade they can be arrested or even shot at. Rajab, a fisherman in Gaza describes one of his experiences with the Israeli navy in an interview with BBC correspondent Tom Bateman https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1 CFqC VNuXs (RECORD OVER) (1:18-1:39)

(Translated) “I was hit in my eye. I was driving the boat, and I fell down vomiting blood and bleeding

I used to see perfectly, now I can’t see beyond three meters.”

So fishing in Gaza is no easy feat and it can come with a lot of risk and as we just heard, physical harm. Further complicating things, the boundary of the blockade changes depending on if there is intensified conflict in the region. Before the blockade in 2007, the boundary was supposed to be set at 20 nautical miles under the Oslo accords which was an agreement between Israel and Palestine that was signed in 1993, however, this is not what ended up happening. In an interview with Al Jazeera, Khaled Abu Rayala describes the shifting blockade:

*https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V6SGjU7eeEs (1:09-1:24) (fisherman talking about the blockade and how it shifts which affects their ability to catch species past 12nm)

“Under the Palestinian Authority we could fish within 20 miles but that only lasted for three months then it was 12 miles but whenever there was tension on land or sea our fishing zone would immediately shrink.”

Since Hamas’ election in 2007, the naval blockade got even more restrictive, sometimes as close as 3 nautical miles from shore. This has had a significant impact on fishermen in Gaza. Khaled goes on to explain how the blockade has affected his family and livelihood:

*https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V6SGjU7eeEs (2:19-2:30) (fisherman talking about how due to blockade he can’t make enough money to feed his family or buy fishing equipment)

“the fisherman is a hunter he needs to go after the fish three miles is a joke I can’t even feed my family or make enough money to buy fishing nets or equipment.”

In addition to not being able to afford the items needed for fishing, the restriction of dual use items makes it harder for fishermen to mend the equipment they do have. So the blockade has restricted control over their territory, means of work, and ability to provide for themselves and their families.

According to Hussein and her colleagues in a paper about fisheries trends and challenges in the Gaza strip, the total fish catch has varied between 1,403 tons and 4,660 tons between 2005 and 2020. The variations in landings can be linked to the shifting boundary of the blockade. This means in years when the blockade boundary is very close to shore like 3 nautical miles, there is less fish caught but when the blockade is further off-shore then the catch increases. So if you’re a Gazan fisherman living under the blockade, the shifting boundary creates uncertainty of where you can fish and impacts whether or not you will be able catch enough fish to offset the costs of fishing.

While the blockade impacts food sovereignty by controlling where and how Gazan fishermen can fish, recall that the Declaration of Nyéléni also highlights the importance of sustainability.

The blockade has the potential to impact the sustainability of fish populations off of Gaza. Fish populations are dependent on spawning grounds which are critical areas where fish eggs are laid. Fishing in areas where fish spawn can lead to species becoming endangered or even extinct. According to Hussein and her colleagues, the main spawning ground is 3 nautical miles from Gaza’s shore and is technically a protected area. However, fishermen in Gaza do not follow that law because at times they can only fish 3 nautical miles from shore due to the blockade.

This could be having significant effects on the overall fish populations but for fishermen that aren’t able to fish past 3 nautical miles they don’t have much choice but to fish in these critical zones. This may affect the future sustainability of the fishery and food sovereignty in Gaza.

Fishing used to be a way for people in Gaza to provide for their families but as the blockade has gotten more restrictive fewer people can depend on fishing as a means of food sovereignty.

I want to end this section with a quote by Amjad, a fisherman in the Gaza strip, he said “I’ve been a fisherman for 22 years. My father was a fisherman and my grandfather before him…all I wish is to live my life with my family in dignity and to be able to sail like other fishermen in the world”.

Tasneem: At the beginning of this episode, we started with the story of the Keffiyeh, which set the stage for why food sovereignty is so important in Palestine. To end, we want to talk a little bit about what is currently going on in Gaza.

In the following clip from December 8th, 2023, Julide Ayger, reporting for Aljazeera describes the situation in Gaza: (video clip discussing starvation in Gaza): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CjMV_xhqsrM (~35 seconds)

“Palestinians like these are spending hours and even days outside un aid distribution centers in Gaza to get whatever food they can but often they’re disappointed ‘I came at 6:00 in the evening waiting at the agency’s door waiting my children are starving we can’t find even a bite of bread our children are suffering due to the lack of bread lack of food we had been told that we would get flour and bread but that was not true.’”

Porter: In January 2024, those in Gaza are currently facing a humanitarian and food crisis. According to a United Nations report titled, “Over one hundred days into the war, Israel destroying Gaza’s food system and weaponizing food”, Gazans now make up 80 per cent of all people facing famine or catastrophic hunger worldwide. That same report says, since October 7th, at least 70% of Gaza’s fishing fleet and multiple ports have been destroyed along with 22% of Gaza’s agricultural land. This is a deliberate destruction of infrastructure that is critical to food sovereignty.

Tasneem: Currently, the world is deeming what is happening in Gaza as a food security issue, urging Israel to allow more humanitarian aid in. And while aid is necessary to address the immediate issue of starvation in Gaza, it’s not a long term solution for food security or food sovereignty.

Porter: Today, our discussion about food sovereignty illustrates that Israeli policies continue to restrict Palestinains’ control over their resources, and their access to culturally appropriate growing and harvesting methods.

Tasneem: Palestinians should not be under threat of violence for fishing in their waters or for harvesting olives from their land. They should have the freedom to grow and prepare food with the culturally appropriate ingredients and to trade goods just as their ancestors did.

Porter: But how can Palestinians gain back control over their food systems and sovereignty under the current Israeli policies?

Tasneem: To start to answer this let’s go back to the keffiyeh. When I went to the pro-Palestine protest in DC this January, all around me I saw protestors wearing the keffiyeh. To me it represented our solidarity with Palesetine and Palestinian’s right to their own sovereign state.

Porter: So maybe, the real question is, how can Palestinian’s have food sovereignty when they don’t even have state sovereignty. What could food sovereignty look like in a free Palestine?

[music: oyster waltz]

Lisa: Thanks for listening to Seas the Day, a podcast from the Duke University Marine Lab. Today’s episode was written and edited by Tasneem Ahsanullah and Porter Porter. Final editing was by Matthew Godfrey. Our theme song was written by Joe Morton and our artwork is by Stephanie Hillsgrove. He can find out more about this and other episodes. From our website, sites.nicholas.duke.edu/seastheday, follow us on Instagram and X at @seasthedaypod. Thanks for listening.

END