In this episode, the students in the Biology and Conservation of Sea Turtles class from the Duke Marine Lab explore the past, current and future status of sea turtle conservation on St. Croix, in the US Virgin Islands. Based on interviews conducted during a 10-day immersive experience on St. Croix, the episode reviews the successes, challenges, and unknowns of conserving and managing sea turtle populations on the island. Part of our Sea Turtles series.

Listen now

Biology and Conservation of Sea Turtles, class of 2022

East End of St. Croix at sunrise. L to R: Nora Ives, Eva May, Jieyi Wang, Jordan Scott, Lilia Moorman, Leah Vogt, Madysen Gilbert, Kelly Stewart, and Matthew Godfrey.

Student Biographies

Nora Ives, who earned a Master in Environmental Management degree from Duke in 2022, is currently an environmental analyst, based in California. She is interested in the power of storytelling to illuminate science, uplift underrepresented voices, and inspire communities as we work towards more resilient and holistic environmental conservation plans. She was instrumental in finalizing this and many other podcasts for Seas The Day.

Website: https://www.linkedin.com/in/nora-ives/

Eva May earned her Master in Environmental Management degree from Duke University in 2022 and is currently a Fisheries Scientist at Monterey Bay Aquarium in San Francisco, California. Eva works on issues related to interdisciplinary marine conservation and applied science, using a multi-faceted approach toward sustainable fisheries management.

Jieyi Wang (iMEP’22 international Master of Environmental Policy) – Jieyi is a second-year graduate student in the Duke-Kunshan Master of Environmental Policy program. During her undergraduate years majoring in marine geology in Tongji University, Shanghai, she gradually found her interest in conservation. From the experience of community social investigation and fieldwork internship, she finds that the local communities are the key to achieving the biodiversity goals, which will also contribute to sustainable development. In the future, Jieyi would like to devote herself to community-based conservation with local communities in China.

Jordan Scott is an undergraduate student at Duke University. She is interested in marine ecology and conservation. She was enrolled in classes at the Duke Marine Lab in the spring session of 2022.

Lilia Moorman is an undergraduate student at Wittenburg University. She is focused on biology, conservation, and marine ecology. She enrolled in classes at the Duke Marine Lab in the spring and summer sessions of 2022.

Leah Vogt is an undergraduate student at Wittenberg University who spent the past spring semester at the Duke Marine Lab. She is studying biology and environmental science and is interested in going into conservation work in the future. She really enjoyed the chance to learn about and see real world conservation efforts for sea turtles in St. Croix.

Madysen Gilbert earned her Master in Environmental Management degree from Duke University in 2022. She is interested in how physical and ecological processes of marine environments are impacted by human activities and how conservation and restoration efforts can combat these effects. She earned her B.S. degree in both Environmental Science and Geoscience at the University of Iowa, where she was a Research Assistant working on paleobiology and biostratigraphy lab work.

Instructor Biographies

Matthew Godfrey is a wildlife biologist with the NC Wildlife Resources Commission. He is also adjunct faculty at the Nicholas School of the Environment at Duke University (Marine Lab) and the Department of Clinical Sciences of the College of Veterinary Medicine at NCSU. He has worked on sea turtle biology and conservation issues for several decades.

Kelly Stewart is a research scientist with the Ocean Foundation and is adjunct faculty at the Nicholas School of the Environment at Duke University (Marine Lab). Kelly collaborates widely with various groups on research related to sea turtle ecology and conservation, and is passionate about contributing to training and mentoring of students who collaborate on different research projects.

Featured in this Episode

We are grateful to staff in St. Croix who agreed to talk to us for this interview.

Mike Evans and Claudia Lombard are wildlife biologists with US Fish and Wildlife Service at the Sandy Point National Wildlife Refuge.

Haley Jackson earned her Master in Environmental Management degree from Duke University in 2021 and worked as an education and outreach specialist with the St. Croix Sea Turtle Project.

Learn more about:

The St. Croix Sea Turtle Project at Sandy Point National Wildlife Refuge

St. Croix Leatherback Project – The Ocean Foundation

Supplemental material for this episode

TRANSCRIPT

Episode 35, Otto Tranberg’s Legacy

[music]

Kelly Stewart:

Welcome Sea the Day. I am Kelly Stewart, adjunct faculty at the Marine Lab. I am excited to introduce a podcast put together by students who visited St. Croix as part of their course on sea turtle biology and conservation. Sea turtle conservation has long been important to the island and the people who live there. Mr. Otto Tranberg and his family began going out to the beach at Sandy Point in St. Croix to protect nests and female turtles, long before it was established as a National Wildlife Refuge. Today, more than a hundred people help patrol beaches, and keep a close eye out for any sea turtles in need of assistance. In addition, St. Croix is where many important studies have been conducted on leatherback and hawksbill sea turtles. This research has revealed information on nest site selection, dive physiology, migrations, lighting impacts, multiple paternity, sex ratios, while various studies continue. Long-term monitoring of various nesting assemblages in St. Croix has produced invaluable data for population assessments and established baseline metrics for improved understanding. St. Croix is also hugely important in providing training and capacity building opportunities for younger people who have come here to work as seasonal technicians or interns on monitoring programs, and also local students who want more skills in marine biology. Let’s turn it over to the students who visited the island last spring.

[music]

Nora: Hi there, my name is Nora and I’m a Masters Student at Duke.

Lilia: and I’m Lilia, a junior at Wittenberg University

Nora: And we’ll be kicking off the episode with a brief overview of the history of sea turtle conservation on the island of St. Croix, and then shifting our focus to Sandy Point National Wildlife Refuge where we had the opportunity to interview one of the legends of sea turtle conservation – Mike Evans. So first off, where is St. Croix?

Nora: St. Croix is a small Caribbean island in the United States Virgin Islands southeast of Puerto Rico, and due south from St. Thomas and St. John. The islands were inhabited by the indigenous Carib and Arawak people prior to European contact by Christopher Columbus in 1493. Soon after the island was settled and ruled by the Dutch and English simultaneously during the 1600s, the Knights of Malta (a religious order) at one point, the French very briefly, and then Denmark from 1733 until the US purchased the island in 1917 for $25 million dollars. During Danish rule “Sugar was King” on the island, and sugar plantations dominated the island’s economy.

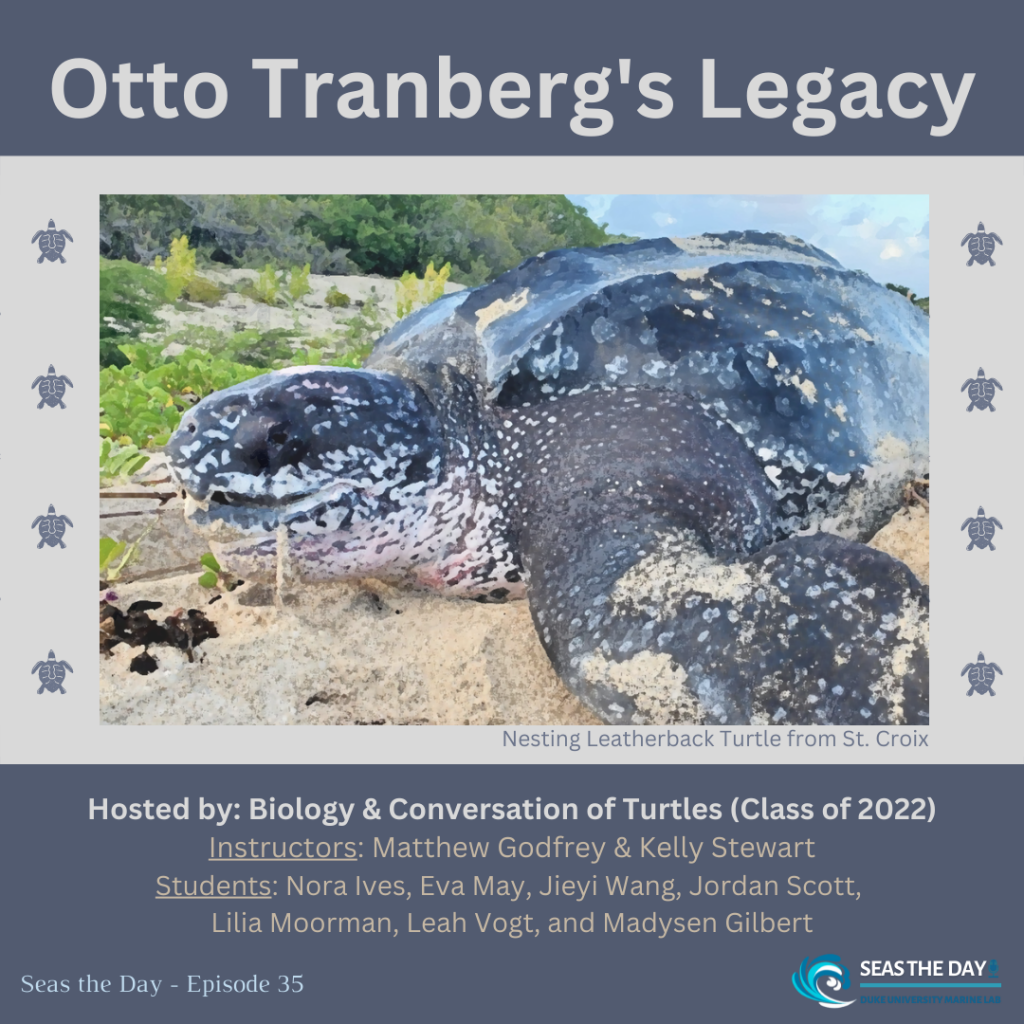

Lilia: Most importantly to our class, several species of sea turtle come to the beautiful beaches of St. Croix to nest, laying over one hundred eggs at a time (depending on the species), which will then hatch out of their nest, erupting from the sand, about 60 days later. The species of sea turtle that come to St. Croix include green sea turtles, hawksbill sea turtles and the largest species of sea turtle on earth, the leatherback turtle.

Nora: Sea turtles have been historically targeted for their meat and beautiful carapaces, or shells. The hawksbill turtle was especially targeted for their shell, which you may recognize in the tortoiseshell pattern on your glasses frame. In 1918 the price of their shell rivaled that of ivory, and throughout the 1920s as many as six nesting turtle were killed each night to be exported from the Virgin Islands to meet the tortoiseshell market demand. By 1975 the international community recognized the need to manage the international trade of all 7 species of sea turtle, and in 1977 the leatherback sea turtle recovery program began tagging efforts at Sandy Point, leading to the establishment of the refuge soon after. The leatherback tagging program at Sandy Point, along with nearby Buck Island Reef National Monument, is one of the longest-term sea turtle monitoring and recovery programs in the world.

NGOs and volunteers have also played an important role in the history of sea turtle conservation on St. Croix. In 1999 the Nature Conservancy purchased land around Jack and Isaac Bay on the east end of the island to protect sea turtle nesting habitat from development and degradation. We got to see this beautiful habitat for ourselves when we hiked around Jack and Isaac Bay as a class to survey the beaches for turtle crawls (which are the tracks nesting females leave after digging their nests) and to also do a beach cleanup, helping to ensure the critical habitat remains pristine.

Lilia: We also got to visit Buck Island is located right off the coast of St. Croix and was established as a National Monument in 1961 to protect the abundance of marine life around the island. It is also a major nesting ground for hawksbill turtles and has one of the longest running sea turtle programs in the world. The establishment of the monitoring and tagging program in 1987 allowed the endangered hawksbill nesting population to make a recovery from 12 nesting females to over 500. The data collected in over three decades of monitoring and tagging is being used to inform management strategies about hawksbill turtles in the Caribbean and Western Atlantic.

Nora: Now we’d like to take you to Sandy Point National Wildlife Refuge. It’s a balmy Caribbean night in late April and we’re sitting beneath the stars on a completely empty beach with absolutely no light. The beach is empty aside from our class, the director of the Refuge Mike, and several volunteers from the St. Croix Sea Turtle Project at Sandy Point National Wildlife Refuge because Sandy Point’s beach is closed to the public. It’s closed to the public because it’s leatherback nesting season and there are no lights, including any flashlights, because any artificial light could confuse the females nesting instincts that have been refined over millions of years. Lilia and I used a lull in patrols for nesting females to ask Mike for an interview. Now Mike is an absolute treasure trove of insight into the wildlife management field, and has led an incredible life. He is full of stories, not all of which we recorded…

Mike Evans: Well, a lot of what I have done in the past we don’t want on record, or else I would probably get arrested. Lilia: We’ll edit that out. Nora: We’ll fix it in post.

Nora: But there was mention of a certain undercover assignment in a circus in Mexico during his law enforcement career where he confiscated 5 polar bears…and then was in charge of relocating them to zoos (the thing about bears is they can switch on a dime he said), another story about a movie star singing an aria on the beach one night in the west indies, an archaeology expedition canceled due to the Falkland war…he’s definitely the guy you want to be wiling away the hours with under the stars waiting for endangered species to haul themselves out of the water to nest…we asked him about his role at Sandy Point and the history at the refuge.

Mike: Well I arrived at this duty station in March 1993 as the refuge manager and at that time it was a one person duty station which meant that the manager title had no meaning. I was basically the janitor and did everything, which was great, great way to approach a job. But um, Sandy Point has been known for sea turtle nesting and in the late 1970s, a combination of sea turtle researchers and members of the staff of the Virgin Islands Department of Planning and Natural Resources had begun doing turtle patrols on Sandy Point. And had not discovered but had verified what a lot of people locally knew was that “plenty turtle dem, come nest at Sandy Point”. The Department of Planning and Natural Resources at that time had two enforcement officers and one of them, Otto Tranberg, was really instrumental in helping establish Sandy Point’s importance as a sea turtle nesting beach but along with a number of key other individuals was part of the effort to establish Sandy Point as a national wildlife refuge.

Lilia: Otto Tranberg was a native Virgin Islander that is credited with almost single handedly preserving Sandy Point as a refuge for sea turtles, especially leatherbacks. He had a fascinating life (I highly encourage you all to look into it) that ended with him back on St. Croix working for the Department of Conservation and Cultural Affairs, currently known as the Department of Planning and Natural Resources. While on the job as an enforcement officer, Otto heard of a sea turtle with its flippers cut off and left for dead. This prompted him to start patrolling the nesting beach at night to protect the turtles and write an article that ended up in the New York Times. The article caught the attention of the Department of the Interior and led to Sandy Point being established as a National Wildlife Refuge. Otto has also been credited as the first person to start tagging nesting turtles on Sandy Point. To memorialize Otto’s contributions, the federal road leading to Sandy Point National Wildlife Refuge is named Otto Tranberg Road.

Mike: And August 30, 1983 was when Sandy Point was established as a National Wildlife Refuge, primarily to manage and protect leatherback sea turtle nesting but in addition hawksbills and greens are a part of that. In the early days, sea turtle monitoring focused on leatherback nesting and it was funded from a variety of sources and in a variety of ways, depended on volunteers. But over the years, the monitoring has evolved as all projects and programs do and we have arrived at a point where I like to think we’re getting not just the most data but we are getting accurate, sound data. But the evolution of Sandy Point and the development of programs here is really interesting because any long term project in wildlife management by its very nature is bound to undergo changes and respond to differing funding events, political issues, management issues and so forth.

Nora – Is there a particular moment where that evolution felt like it leapt forward for you that you could share, like a turning point?

Mike – Absolutely, yeah, and that came when we literally went to a team managed by refuge staff and NOAA staff. In the past of turtle monitoring teams were supported by contract and volunteers and volunteer programs and they were great and they were effective but ironically the refuge was established to manage and protect sea turtles. But the refuge never really had direct control of the sea turtle monitoring programs. And so over time, we were able to get refuge funding and apply that towards sea turtle management and we were able then to assume the direct hands on management of sea turtle monitoring. So by the refuge being able to assume management and direct funding support of turtle work on the refuge the VIDPNR was able to take its entire endangered species and wildlife management grants and support work on the balance of the island.

Nora – So kind of redistribute the resources that way, more equitably.

Mike – Exactly and I like to think it was a win-win for everybody because one of the first things that I was aware of with turtle work in Sandy Point was that sea turtles nest on beaches, this island has officially 52 beaches, Sandy Point is only one. Right now we are on the beach and other than sea turtles we are the only ones out here. Why, well Sandy Point is closed seasonally to the public because of the data we have received from sea turtle monitoring and research here.

Nora – So when was that closure implemented? How long did that take?

Mike – It actually was implemented about 1994, late 94, early 95, and it was not popular in some segments of the community but we were able to explain and justify why we closed Sandy Point, the data behind it and why it was important to close Sandy Point in order to maximize nest hatch success. The reason we don’t have pick up trucks and horses and tents and bonfires on the beach, we can say no to that because the data we have from sea turtle monitoring shows us not only that it would impact sea turtles but the extent, the degree that it would impact. Peak of the leatherback nesting season we could have within two or three days anywhere, in previous years we have had anywhere from fifteen to maybe thirty or forty nests that were close to emergence and if somebody drove a four wheel drive jeep or pick up down the beach it could literally wipe out thirty or forty percent of hatchling production for the season in one event of a vehicle going down the beach.

Nora – I know we do not want to put anything on the record that is incriminating but are there any stories from your several decades here that really stand out as incredible memories on the beach monitoring or any other incredible encounters with wildlife here.

Mike – Well the most incredible thing about this, I think what is most remarkable is that seeing sea turtles, greens, hawksbills, leatherbacks all the time, what I find so remarkable is that after thirty years of watching them here and another two decades, I have been in the West Indies most of my adult life, fifty years or more and I have seen a lot of sea turtles, like the most remarkable thing about it is every time I see one it is almost like the first time. You know these species have to be pretty darn remarkable if you can spend your adult life watching them, seeing them, encountering them and still be just as excited and interested in them after fifty years of doing this than the first sea turtle I ever saw. No rational person can ever become jaded at the sight of a leatherback nesting but leatherbacks were leatherbacks before dinosaurs became extinct so when we watch a leatherback nesting on a beach, we are watching a species that was doing the very same thing when there were still dinosaurs, the last of the dinosaur were still roaming the earth so I think it is a remarkable direct connection to frankly the longevity, the whole chain of life and that is part of what makes it so exciting to get to see a sea turtle.

Nora – Thank you Mike.

Mike – Oh sure, certainly.

[transition]

Mads: Hi my name is Mads and I’m a Master’s student at Duke,

Jieyi: My name is Jieyi, a Master’s student at Duke

Jordan: My name is Jordan, an undergraduate at Duke

Mads: We looked at current sea turtle conservation on Saint Croix. As mentioned earlier in the podcast, there are three species of sea turtles that currently nest on beaches in St. Croix. All three of these species- hawksbills, green sea turtles, and leatherbacks- are endangered. The Endangered Species Act designation provides these turtles with critical habitats- one of which is Sandy Point National Wildlife Refuge in St. Croix. Last year at Sandy Point, there were 94 leatherback nests, 1399 green sea turtle nests and 234 hawksbill nests.

Current efforts for turtle conservation are seen all over the island. We spoke to Claudia Lombard, a Wildlife Biologist for the US Fish and Wildlife Service at Sandy Point. Claudia can be heard here telling us about the many groups working with sea turtle conservation on the island.

Claudia Lombard: So number one, we have the US Fish & Wildlife Service and then we have a partnership with the Ocean Foundation. There’s also the National Park Service, who focuses their work out at Buck Island National Monument with the Hawksbill project. And then there’s the Nature Conservancy and they’re out on the East End of St. Croix at Jack’s and Isaac’s Bay- I’m not sure if you all made it down there or not but it’s a beautiful hike and some great snorkeling if it’s calm on the south shore. And then St. Croix Environmental Association, they manage Southgate Coastal Reserve. And then there’s East End Marine Park, which is part of the local Department of Natural Resources, and they have a volunteer network who monitor some beaches around the East End that don’t get a lot of turtle activity, but are important to monitor and to know. So there’s a lot of us.”

Mads: And these are just the groups working on monitoring beaches and nesting. There is also STAR, the Sea Turtle Assistance and Rescue Non-Profit, who responds to strandings and emergent situations with turtles. Although there is an abundance of groups working on sea turtle conservation, Claudia focuses on Sandy Point. Here she explains how their numerous efforts feel like one big program.

Claudia: At Sandy Point, specifically, I like to call it one big sea turtle program, but it encompasses a lot of different activities. We have our long-term leatherback sea turtle program, where we’ve been studying and monitoring nesting trends for our leatherback turtles for, it’s been, since before this became a national wildlife refuge, started in 1977 by a local superstar named Otto Tranberg, who came to the beach and saw poaching and saw the need for protections, so he started the conservation efforts here. In 1984, the federal government purchased the land and it became a national wildlife refuge, really for the purpose of protecting leatherback turtles, so we are continuing that project now. So we have our leatherback program where we have saturation tagging where every turtle gets a tag and we are able to monitor the trends of the population over time, where the population is growing, stable or going downward. And through that knowledge, we can then implement management strategies. So that would be our leatherback program, and we have a green and hawksbill project as well. Long-term that’s been more morning surveys where we document tracks of turtles, but we can get to similar information that we do with leatherbacks, just by documenting tracks, so we can look at population trends there as well.”

Mads: All of these efforts, from beach patrols to tagging, have allowed us to estimate population size changes.

Claudia: For our leatherbacks in particular, since we have been studying them for so long, we saw the population trend just skyrocket up in 2009 and then just in our recent past 5 years, we’ve seen that population- in don’t know if I’d call it crash- but it’s pretty significantly decreased. So yeah, being out there, if we weren’t doing the work that we’re doing, tagging turtles and monitoring them on the beach, then we wouldn’t know that this is happening. And this trend is a regional trend, so it’s not just happening on St. Croix, it’s happening throughout the Caribbean. Where all the nesting beaches for leatherback sea turtles are seeing decreases in their numbers.

Jordan: Despite all of these efforts to patrol beaches and tag turtles, it is hard to monitor turtles when they are not on the beach. Many migratory patterns are not entirely known and from the time hatchlings leave the beach, to when they return to nest, little is known of their location or behavior. Because of this knowledge gap, it is hard to determine the reasons for population fluctuations.

Claudia: So that’s to be determined. So it’s- we’re not exactly sure why it’s happening. It could be a number of different factors from something that’s happening during their migration routes or during their time in their foraging grounds, it could be they’re not able to find males, it could be they’re moving to different beaches… so there’s a lot of potential reasons we’re seeing these decreases and that’s why we have added a few different research projects that are specifically looking at answering those questions. So one is satellite telemetry, so we’re attaching satellite tags both here on St. Croix and in Puerto Rico to track our turtles, both in their inter-nesting movements, so leatherbacks will nest 4 to 5 times each season so what are they doing in between that time, and then also their migrations, so we’re interested: are they using other beaches for subsequent nests after they leave Sandy Point, could that be a reason maybe we’re not seeing them.

Jordan: While these fluctuations may sound concerning, it is important to understand that from the perspective of population biologists, these short-term fluctuations may not be a cause for concern.

Claudia: I mean if you’re a population biologist you know that there are natural fluctuations in populations, so I’m hoping that with our leatherbacks that maybe that is the case. Maybe this is just a natural fluctuation, we’ve got ups and downs, and oscillations and those trendlines.

Jordan: While patrolling beaches, tagging turtles and monitoring populations are all important techniques for turtle conservation, utilizing outreach and education is often overlooked. Data and research are not useful if no one in the community is willing to implement techniques supporting them.

Claudia: I think it might be, I have a tendency, although my job is as a biologist, I have a tendency to look at the social aspect of things. So I always want a community that really just supports the work that we’re doing. And we do have that, it’s just not across the board. I would love for us to be able to have the staff to go out into the community more, you know, represent the refuge and turtles and conservation in general at all the different events that happen within the community and have more ability to bring people here and show them the resources. So I think that might be one thing, I do think it’s really important that we have a community that’s involved and that can appreciate and then support and then fight for it.

Jordan: Community engagement is vital for successful conservation programs. Finding ways to inform people on the island can help foster awareness and interest for protecting these endangered species.

Claudia: St. Croix is missing outreach that concerns wildlife or conservation, so there’s no zoo, there’s no natural history museum, there’s no aquariums, there’s no outreach centers that focus on conservation, so the Turtle Watch Education Program is like the premier, although I might be biased, program on St. Croix, that really gears itself toward the local community and toward youth to give them hands-on up-close, incredible experience observing wildlife and learning about why it’s important.

Jordan: To get a closer look at the program, we talked with Haley Jackson, the Saint Croix Sea Turtle Project Education and Outreach Specialist. She told us about her experiences with the program and about the interest from the local community.

Haley: They all seem so excited to get to learn about the sea turtles. For many of them it’s their first time ever seeing a sea turtle, and maybe you know, many of them it’s their first time getting to see one nest, getting to see them hatch. So the up close opportunities that Turtle Watch presents to the community groups that come out is really quite valuable. They really enjoy getting to sit and enjoy listening about turtle biology and conservation, and then getting to see kind of what we just talked about in person with the nesting and the hatching.

Jieyi: Oftentimes, community efforts struggle with lack of retention. However, Haley has noticed that this does not seem to be the case here.

Haley: We often have many groups that return year after year that have been coming to turtle watch for a while now. A lot of the kids seem involved in knowing the information, especially if they’ve come out before. I had a group just the other night who had been out on a hatching watch last year and they knew all of the answers to my questions and seemed like they had really retained what they learned when they last came out with the program.

Jieyi: Claudia has also seen success with retention in the community and is even recognized by former participants.

Claudia: You know, it’s kind of cool being in the grocery store picking up my milk and “Oh! You’re the lady from the turtles.” People know the program and people come back and tell me about it, you know, “Oh! It was so great. We saw all these hatchlings emerging from the sand and it’s so wonderful.” So the people that do come out to our program, I think it really makes a difference.

Jieyi: Even though these programs have been and continue to be successful, it’s always important to reach out to a wider audience.

Haley: We always want to get new groups coming out to learn about the sea turtles. And so I think being able to have more of these programs would help increase the chances of having more of the youth of St. Croix and the Virgin Islands able to be understanding and learning more about sea turtles and their conservation.

Haley: We just want to make sure that we’re reaching out through as many avenues as possible and I think we are looking to expand. We love when we have groups come back, but we also want to see people who have not had the chance yet to come out on a Turtle Watch have that opportunity and so I think just finding different ways to reach out to the community and the islands is where we are still kind of working through, but we have been doing a good job of trying to do some different outreach and asking people how they’re hearing about us so that we know what’s a good way to broadcast the information to the community.

Jieyi: Despite the visibility of turtle programs all over St. Croix, there is limited collaboration between the organizations. The demanding nature of turtle research often leads to overworking and understaffing, leaving little time for external collaboration. We asked Claudia what she thought about collaborating with other organizations working on turtle monitoring in St. Croix.

Claudia: …it would really be great, and we do, from time to time, but I think because we’ve got limited people and because all of our plates are full, although, it would make sense because we could share certain responsibilities, we just don’t initiate it because we are just busy from the start of the work day to the end of the work day. But I’d like to see that, and, you know, the people above us want to see those kinds of collaborations too. “Oh! We have this funding, but we want to see you working with your partners.” So it’s a great idea and we need to do it more. And we have just started more recently. There was sort of…some new, young people in these positions and we have a really great network of people working in conservation right now. So it might be a good time to start.

[transition]

Eva: Hi everyone, we’re Eva May, a Master’s student at Duke,

Leah: and Leah Vogt, an undergraduate student at Wittenberg,

Eva: and we’ll be finishing things off today as we discuss the future of sea turtle conservation in St. Croix.

Leah: That’s right! Over the past two weeks, we spoke with folks at the US Fish and Wildlife Service, the National Park Service, and the St. Croix Sea Turtle Project to learn more about what ideas, concerns, and desires will help shape the future of local sea turtle conservation.

Eva: But before we dive into some of our takeaways, we want to give you, the listeners, a chance to hear from these important voices yourselves. We asked three of the wonderful ladies in St. Croix the same question: If you could choose one thing to focus future sea turtle conservation efforts on in St. Croix, what would it be, and why?

Leah: First we’ll hear from Haley Jackson. You might remember her from the current conservation efforts section of this episode. Here’s Haley’s response to our question.

Haley: Uh I would choose to focus on increasing the educational opportunities available at the refuge. Uh, we currently just have a few programs and I think it’s super important to increase the opportunities for the St. Croix youth um specifically because they are the future of the island and the planet, and so giving them more opportunities to learn about uh not only what’s in their backyard and around their island uh but what the importance of conservation means for different species.

Eva: The importance of education and outreach is definitely something we heard about a lot during our time in St. Croix. We asked Claudia Lombard, whom you also heard from earlier in the episode, this same question, and her response also touched on the theme of environmental education, as well as the preservation of land.

Claudia: I guess I’m gonna have to go the route of of outreach and education. There’s just no denying what impacts… on conservation you can have when you have a community that supports the conservation work. Us being a small refuge with a small staff, it’s hard to get that reach out into the community but I think it’s really important. Although we’re a very small refuge the work we do rivals the work that’s done on those you know Alaska refuges that are tens of thousands of acres… so I think getting out more into the community, into the schools, um, providing more programs, giving input into the curriculum of schools cause there’s not a lot of in the school curriculum, there’s not a lot of um subject matter dealing with natural resources or conservation so working to implement that, um working with the Department of Education to get more conservation into the school curriculum. Here at Sandy Point, providing more programs um where the community is invited to learn and enjoy wildlife and the habitats we have. Of course we need to continue our monitoring programs and our research and our management efforts at Sandy Point and throughout St. Croix and [again] yes I’d like to see more land um put aside for conservation, less development, which we’re in sort of a lull right now so {I/uh] guess it’s not at the top of my mind so there aren’t big um… development projects that are coming up in the near future so that’s a positive um so besides conservation of land for wildlife protection of habitat for wildlife I think it’s really getting out in the community and sharing um [the/a] conservation ethic and if you have a community that understands the resources that sees it that can appreciate it they’re informed of the… threats to wildlife and the, importance of conserving habitats if you have a community that’s on board with your mission then that’s I think irreplaceable.

Leah: Finally, we asked Kelly Stewart, who works for the St. Croix Sea Turtle Project at The Ocean Foundation, what she would focus future conservation efforts on. Kelly’s response touched on a different theme that we heard during our conversations: that of building collaborations and standardizations across efforts.

Kelly: I would choose to focus on implementing standardized surveys across the 3 Virgin Islands for the entire calendar year so that we can get a really accurate picture of the seasons for each of the 3 sea turtle species and then that will help us make conservation priorities in the future so what our metrics are in the future and how close we are to achieving those. I think that this would also help us establish Sandy Point and St. Croix as a regionally significant nesting beach for hawksbills and green turtles which it hasn’t been designated in the past and I think all those things would help.

Eva: As someone who’s used long term datasets in a lot of my own work, Kelly’s response certainly resonates with me. During our time in St. Croix, we heard from Makayla Kelso, a future St. Croix Sea Turtle Project employee and current master’s student in St. Thomas, about the importance of long-term monitoring in sea turtle conservation. This kind of monitoring should continue in the future, and standardizing data collection helps to ensure data are comparable across locations and efforts. This also helps us understand nesting seasons and timing across the three species in St. Croix.

Leah: I completely agree. I also was thinking about just how much work goes into the constant monitoring at Sandy Point and how this would translate to monitoring other St. Croix beaches in the same manner. Between leatherback, green, and hawksbill turtles, there are a few dozen total nesting beaches on the island, some of which are monitored only occasionally and some of which aren’t monitored at all. I think one theme of future conservation is the desire for expansion, especially beyond just Buck Island and Sandy Point, but this is constricted by staff capacity limitations. Sandy Point itself just has two full time US Fish and Wildlife Service Employees, and other beaches don’t even have that.

Eva: That’s a really good point and makes me think about what we heard from some folks about collaborations. From what Claudia said, it seems like there’s a pretty large desire for increased collaboration between the different government conservation groups. When we worked with Kristen Ewen, a National Park Service scientist working on the hawksbill monitoring project at the Buck Island Reef National Monument, she and Kelly were talking about the irony of being so close geographically but never having the time or ability to work on projects together. But, maybe if the government is pushing for this, staff capacity could be increased, and collaborative projects could help fill the current conservation and monitoring gaps.

Leah: It does seem like the desire is there, it’s just a matter of fitting collaborations into what seems like an already packed schedule for everyone working on sea turtle conservation in St. Croix. Volunteers can also be a big help in increasing capacity, but it can be difficult to manage them without having an official volunteer coordinator, which is also something that could be helped by increased collaborations. In thinking about capacity limitations, I’m also reminded of what we heard from Claudia and Haley. Both women are engaging, passionate speakers who recognize the importance of creating human connections to the environment and to each other. It seems like they both really want to be able to do more when it comes to community outreach.

Eva: Yeah, and I agree with them about the importance of this. If you can get someone out into the environment, teach them about why nesting beaches are important, show them a turtle, and create a personal connection with them, they’re more likely to support your cause. From what we saw at Sandy Point, the current outreach and education efforts are definitely making an impact in the community, and I hope they’re able to broaden the reach of these efforts not just for Sandy Point, but for all of St. Croix, in the future. To help our listeners feel and understand this connection, we have an audio clip of a nesting leatherback. It was really incredible to be up close and personal with these turtles, and listening to them breathing during egg laying felt like a trip back in time – they sound like big dinosaurs!

Leah: I’ll never get over how cool of an experience that was. I felt really connected to the nesting mothers, but also to the people who worked with them. It surprised me just how much human connection and dealing with people plays a role in conservation there, and really anywhere. When we talked to Mike Evans, whom the listeners heard from in the past conservation efforts section of this episode, he talked about the threat of beach development and the politicization of science and the environment. From our conversation with Claudia, it seems like beach development is not an immediate threat, but if a development opportunity was presented, the government would be on board. Mike said they’ve been successful in connecting with locals by understanding the role their culture and history plays in how they view conservation, and I think lessons like this are important to bring into future work. Maybe community members would be more likely to oppose development and support conservation if they felt that conservation managers were connecting with them on a human level.

Eva: Totally. And I think talking about environmental issues, like Mike was saying, has become, unfortunately, kind of a polarizing conversation. But it doesn’t have to be this way, and I think programs like Sea Turtle Watch, which gets kids, college students, and adults of all ages out onto Sandy Point and up close with the turtles, really help with pushing past this. Just continuing that community outreach and understanding has a real potential for increasing local support and even increasing the potential work and volunteer force for sea turtle conservation in the area.

Leah: Yeah! And I loved how Haley said that even when she moves on to her next career step, she won’t ever really be fully leaving the Sea Turtle Project. She said she’ll always at least be available for remote volunteer work, and I think that sense of long-standing community and connection is really important in conservation work.

Eva: Me too. But, going back to this idea of the politicization of the environment and science, I think we do, as the future conservation section, have to talk about the elephant in the room: climate change.

Leah: Right, of course. I think when we started on this podcast section, we thought the whole thing would be focused on climate impacts and how they would affect future work. But now we’ve spent the past ten minutes talking about other human aspects of conservation.

Eva: I know! But, we did hear about and see some of the effects of climate change while we were there. On Sandy Point’s south shore, erosion is already starting to wash away the beach, which hasn’t been helped by recent hurricanes damaging or ripping away shoreline vegetation. Claudia talked about the need to continue monitoring sea level rise impacts, especially because they’re already being felt there. If there aren’t beaches, where will St. Croix turtles nest? And, what would be really tragic, is if St. Croix beaches were doubly harmed by both development and sea level rise.

Leah: Hopefully we don’t see that, and I think the work done by the folks we spoke to and worked with is already making strides toward preventing this. While future conservation efforts can’t exactly stop climate impacts that are already in motion, they can increase our conversations about them, and they can also stop impacts from other human threats to conservation that haven’t started yet. I definitely think that, even though projects like the St. Croix Sea Turtle Project and operations like that at the Sandy Point National Wildlife Refuge may be small, their impact is huge, and they can continue to make a difference in the future.

Eva: I’m confident they will!

Eva: Thanks so much for tuning in to our episode about sea turtle conservation in St. Croix. All of us are really grateful that the conservation folks in St. Croix let us help and learn from them, and we’re excited and hopeful for what the future holds. We hope this inspires you to get involved in conservation, because each individual really can make a difference.

Matthew Godfrey: Thanks for listening to the first sea turtle episode from Seas The Day. Today’s episode was written and recorded by Madysen Gilbert, Nora Ives, Eva May, Lilia Moorman, Jordan Scott, Leah Vogt, and Jieyi Wang. The episode was edited by Nora Ives. Learn more about today’s episode and find past episodes on our website at sites.nicholas.duke.edu/seastheday. The theme music was written by Joe Morton, and the artwork was created by Stephanie Hillsgrove. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter @SeasTheDayPod and don’t forget to leave us a rating wherever you listen to your podcasts.

References, general:

https://usvi.net/st-croix/seven-flags-the-history-of-st-croix/

https://www.arcgis.com/apps/MapJournal/index.html?appid=9a963174e35c4c24aeec0b7b77410a7e

Fish and Wildlife conservation plan document pdf:

https://ecos.fws.gov/ServCat/DownloadFile/18981

Otto Tranberg references:

https://stthomassource.com/content/2017/12/12/community-mourns-passing-of-otto-tranberg/

https://visourcearchives.com/content/2008/07/14/island-profile-otto-tranberg/

https://www.nytimes.com/1979/06/24/archives/turtlewatching-on-st-croix.html

Buck Island references:

https://www.nps.gov/buis/learn/historyculture/index.htm

https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/why-sea-turtles-returned-to-buck-island.htm