By Kelli Morrissey

When asked by friends and family what I am up to this summer, I often have a hard time communicating exactly what it is that I do here at the Duke Superfund Research Center. I work with zebrafish tissue samples to study… humans? But how? Aren’t we quite a few million years removed from our friend Nemo on the tree of life? Well, it turns out that zebrafish are actually a great model organism for studying humans due to their very similar organ systems, fast reproductive timeline, and transparent embryo membranes (you can watch development as it occurs! Check out this graphic). Who knew!

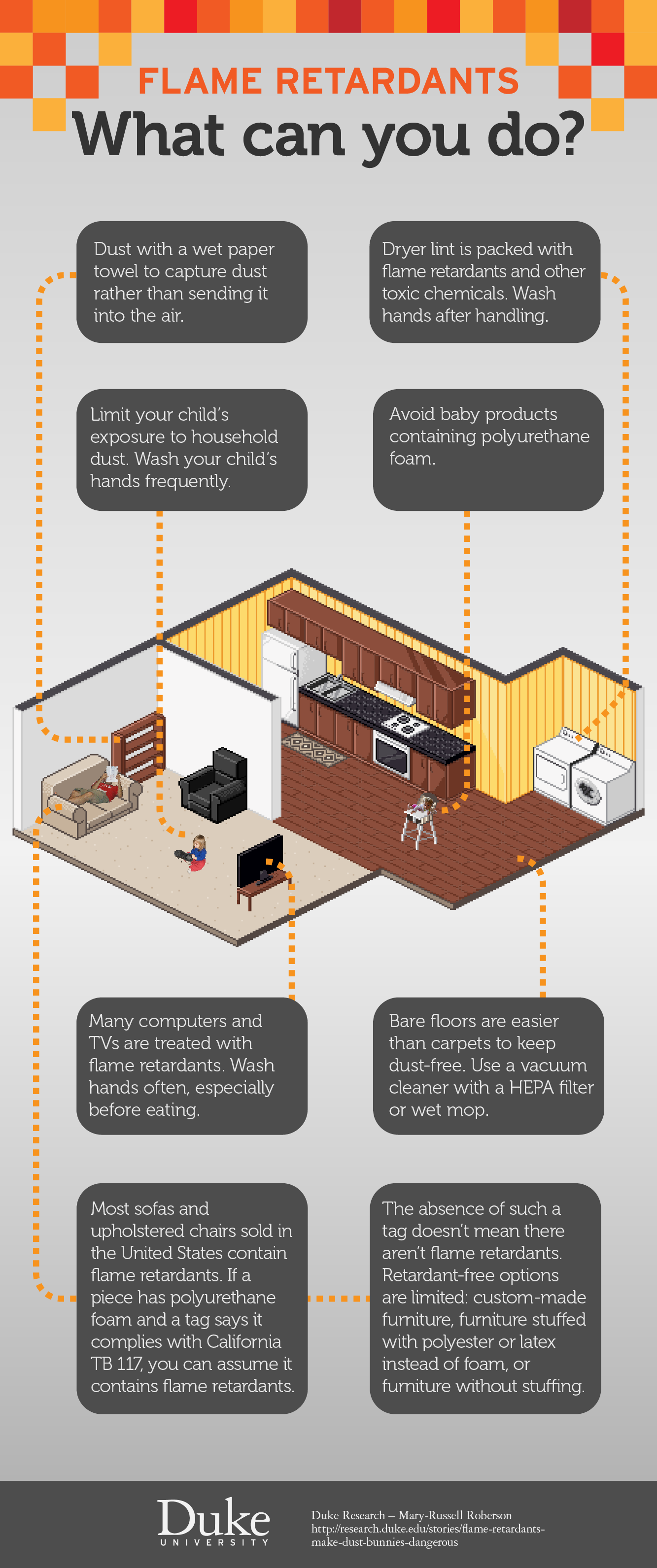

So, now that we understand why I am working with fish when I am really interested in studying humans, let’s get down to exactly what I am looking at. In recent years, flame-retardants have come into the spotlight as a controversial chemical tool. On one hand, flame-retardants are thought to lower the risk of deadly fires in human environments by their addition to anything from furniture to pajamas; however, on the other hand, these chemicals may actually be harming the people and environments they are intended to protect. Check out the following series of articles on the dangers of flame-retardants that took center stage in the Chicago Tribune recently. My study focuses specifically on how brominated flame-retardants affect human metabolic development. One of the main organs involved in metabolic development is the thyroid gland, an organ that produces various thyroid hormones in order to regulate metabolism and development (Interested in learning more about the thyroid system and its key players? Click here). The human thyroid system and zebrafish thyroid system act very similarly, allowing us to make inferences about humans from studies of these tiny fish. Measuring the concentration of these hormones in tissues allows us to make comparisons between normal, or control, and exposed fish. If an embryo is exposed to a flame-retardant and has a level of hormones that varies from what would be expected in a control embryo, it may be a sign that flame-retardants are up to no good when it comes to development.

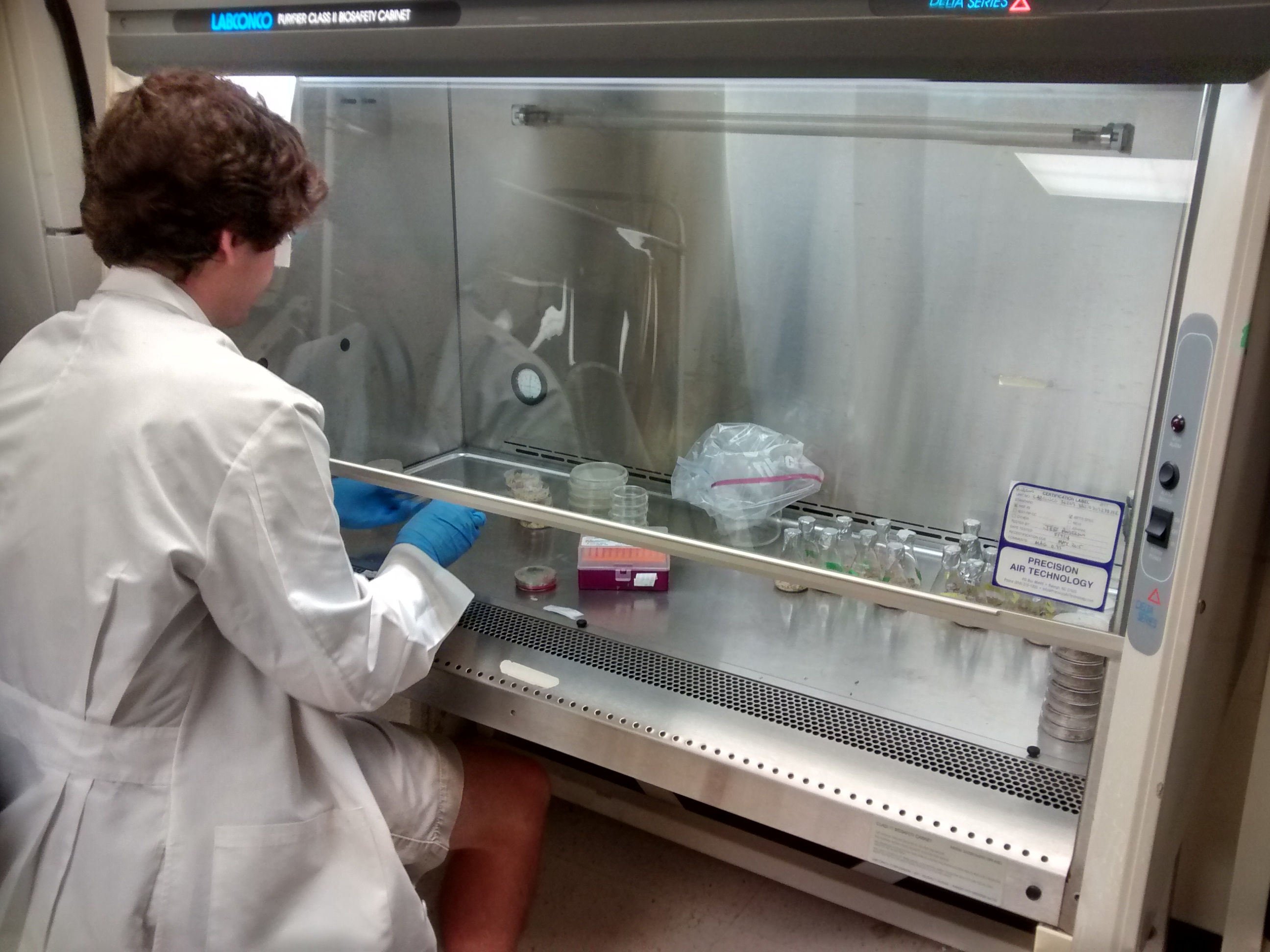

My summer has involved a large amount of method development. The method I am currently using to measure the thyroid hormone levels in zebrafish tissue was initially used to measure thyroid hormone levels in rat brain tissue, and it didn’t transfer over perfectly. As a result, I have spent the majority of my time at the Superfund Center tweaking the original protocol, or set of experimental steps, and making educated guesses in order to get sufficient data output from the fish tissue to complete meaningful studies. The protocol is finally returning acceptable data, and it is so rewarding to know that I played a major role in developing a method that really works. Exposures and comparisons are the next step as this study moves forward, and I am excited to see where these results take us. It would be really cool to make a difference in the lives of people by finding out something important about the chemicals we come into contact with on a daily basis.