Joshua Berg

Aquaculture – Is it Really the Answer?

According to NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association), aquaculture is the rearing, breeding and harvesting of plants and animals from marine environments of all types.[1] This method of food production has become increasingly popular in recent years, as increased demand for seafood worldwide has triggered the heavy industrialization of the aquaculture industry. Ideally increased aquaculture would lessen the stress on natural fisheries that are threatened by overfishing and other factors.[2] However, this rapid evolution of the industry has created unforeseen consequences that need to be addressed, as the industry shows no sign of slowing growth.

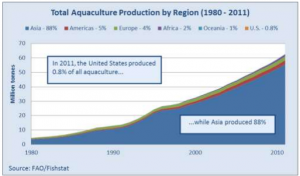

Over the past 30 years the production of certain fish, shrimp, clams and oysters worldwide has more than doubled in its harvest weight almost exclusively due to aquaculture. As catches in marine animals raised in aquaculture increased as expected, catches of wild caught species remained the same.[3] This trend is concerning as one of the main reasons for investing in aquaculture facilities is to lessen stress on the ocean’s endangered fisheries. Let’s discuss the reasons as to why aquaculture has not achieved the main goal of lessening stress on the ocean’s fisheries and whether or not aquaculture is a viable and sustainable method of seafood production.

Total Aquaculture Production by Region from 1980-2011

http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/aquaculture/docs/aquaculture_docs/world_prod_consumtion_value_aq.pdf

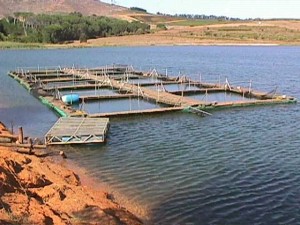

Aquaculture facilities vary greatly as a multitude of factors contribute to what equipment and location is best suited for a specific site. There is also little government oversight of aquaculture facilities around the world due to the rapid expansion of the industry. This lack of regulation has had its share of detrimental impacts on the environment consequently putting increased strain on the wild fisheries many aquaculture operations intend to protect. The world’s leaders in aquaculture predominantly located in Asia, have yet to strictly enforce industry standards.[4] As a result many vital habitats along coastal areas have been destroyed. Specifically mangroves and coastal wetlands have been exploited by aquaculture have been transformed into to breeding ponds for various species. However, these areas consequently lose their ability to provide essential environmental services such as flood control and nutrient filtration. The loss of these services damages the wild fisheries located in the proximity of aquaculture operations and once again places additional stress on the wild fisheries.

One of the most concerning consequences of aquaculture that can occur if facilities are not managed properly is the escape of non-native fish and the contamination of wild fishery gene pools.[5] Many breeds of fish and mollusks raised via aquaculture are genetically modified or different than their wild counterparts. The mating of native and non-native species has occurred as aquaculture’s presence has increased. A clear example of this escape and contamination of wild fisheries can be found in the case of the Atlantic Salmon. Atlantic Salmon is major farmed species of salmon worldwide and while they are supposed to be highly contained in aquaculture, it has been found that nearly forty percent of wild caught Atlantic Salmon were initially bred in an aquaculture.[6] This decreases genetic variability in the Atlantic Salmon making it more difficult for the species to evolve when natural conditions change, therefore making the species more susceptible to disease and other natural disasters. Despite these negative consequences of aquaculture there are positive benefits as well.

Aquaculture Facility in Asia

http://www.elsenburg.com/trd/animalprod/akwa/images/facilities4.jpg

The United States currently ranks 15th worldwide in the amount of seafood produced through aquaculture, leaving significant room for growth in this industry. If growth in this industry follows the increasing demand for seafood, it is estimated that by 2025 there could be between 180,000-600,000 American jobs created.[7] These jobs would be located primarily in coastal regions that are currently suffering from declining fish stocks. In addition, the seafood industry currently has a deficit of $6 billion dollars second only to oil.[8] Increased aquaculture would lessen America’s dependence on foreign economies stabilizing the domestic seafood market and potentially creating an additional export.

With both positive and negative consequences of aquaculture creating a difficult crossroads, it will be interesting to observe how the United States will implement aquaculture facilities around the country. Regardless of aquaculture’s future success, or lack there of it is crucial to keep in mind that there must stringent regulations placed on operators in order to ensure the smallest amount of collateral damage to wild fisheries. I believe that if aquaculture operations are managed responsibly and proactive measures are taken such as preventing fish escape and producing fish feed sustainably that aquaculture can successfully reduce stress on wild fisheries.

[1] http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/aquaculture/what_is_aquaculture.html

[2] http://www.seafoodwatch.org/cr/cr_seafoodwatch/issues/aquaculture_wildfish.aspx

[3] Naylor, Rosamond L., and Rebecca J. Gouldburg. “Effects of Aquaculture in World Fish Supplies.” Issues in Ecology (2001): 1-12. Print.

[4]http://www.seafoodwatch.org/cr/cr_seafoodwatch/issues/aquaculture_habitatdamage.aspx

[5] http://www.seafoodwatch.org/cr/cr_seafoodwatch/issues/aquaculture_escapes.aspx

[6] Naylor, Rosamond L., and Rebecca J. Gouldburg. “Effects of Aquaculture in World Fish Supplies.” Issues in Ecology (2001): 1-12. Print.

[7] http://biology.duke.edu/bio217/2005/ncm3/benefits.htm

[8] http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/trade/DOCAQpolicy.htm